Words that bring the dead to life

[Above: James Barton Longacre, Harriet Livermore, 1827, Stipple engraving on wove paper—[CC0] National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution]

Revival is about life. Revival preaching is life-giving. But how can the dead be revived? By a magical incantation? Through a jolt of electricity, as in the Frankenstein story? Or by means of a cryogenically frozen body that future scientists will restore to life? The Christian answer is none of the above. Life comes from God; specifically from his Word: “Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that comes from the mouth of God” (Matt. 4:4). God’s Word is “living and active” (Heb. 4:12), giving life because it contains life, or, rather, is life. The written text manifests and conveys the eternal Word, who is Christ himself.

A favorite text for earlier revival preachers was not “you must be born again” (John 3:7), nor the apostle’s call to “be reconciled to God” (2 Cor. 5:20), but a vision about a valley of dry bones that came to life (Ezek. 37). The Lord could himself have commanded the bones to grow flesh and come alive, but had Ezekiel give the command. Revival preachers are like Ezekiel, under a divine mandate to speak life to dry bones.

Here are some key questions about revival preaching.

QUESTION: What is “revival”?

MICHAEL MCCLYMOND: Philip Keevil wrote,

Revival is . . . when the people of God are keenly aware of God’s felt presence among them; when spiritual things increase in their reality; when the impact of God’s truth is felt more poignantly; and, when there are signs of deep wounding, as well as genuine healing, as a result of . . . the Word of God. (See p. 4 for more.)

Q: Why is revival necessary?

MM: The Old Testament shows a cyclical pattern among God’s people, with phases of decline followed by periods of renewal. Jonathan Edwards said that revival is needed because God and spiritual things do not seem real to most people. “Believing the truth” differs from “having a sensible idea or apprehension.” Yet a divine “light cast upon the ideas of spiritual things . . . makes them appear clear and real which before were but . . . obscure representations.” What had been merely conceptual is now seen, tasted, and felt. For Edwards this sensing of divine reality comes through preaching. His sermonic word-pictures—or his “rhetoric of sensation”—sought to make spiritual things perceptible to his hearers.

Q: Is revival for the sake of believers or for nonbelievers?

MM: Both. Periods of spiritual outpouring stir mature Christians to renewed fervor, but also bring conversions of people who seem like improbable converts.

Q: What role does preaching play?

MM: Recent authors focus on revival praying rather than revival preaching. While prayer is crucially linked to revival, it ought not eclipse preaching. Historian Eifion Evans wrote:

Historically, there has been a close relationship between preaching and revival. Those revivals that have been the purest and most beneficial have given a preeminent place to . . . preaching.

Though his critics accused him of emotionalism, revivalist Charles Finney taught that “in the work of conversion…the instrument is the truth.” Emotions alone cannot effect genuine conversion. There must be a presentation of truth and a call to personal decision based on truth.

Q: What truths have been central to revival preaching?

MM: Revival preaching involves a recognition of radical sin and corruption in human life; the conviction that sinners are spiritually lost and unable to save themselves or escape God’s judgment; that God alone saves and forgives, cleanses, and renews those who trust in Christ; and that God’s forgiveness is complete, since Christ made full atonement for sins.

Q: Does revival preaching differ from standard preaching?

MM: While effective preaching should appeal to the human will, the call for a decision is inescapable in revival preaching. A message with no call for a decision is not revival preaching. Decision, though, does not happen in a vacuum. Listeners must be moved toward concern, and unconverted sinners perceive their condition apart from God’s mercy in Christ.

Q: What effect does revival preaching have?

MM: The hearer feels as if God has “found him out.” Historian William Arthur wrote:

An unaccountable impression of God’s presence, of . . . a warning, a call from God, sinks down into his soul . . . Falling down upon his face, forgetful of all appearances . . . he worships . . . an offended but a forgiving God.

Q: Has revival preaching changed over time?

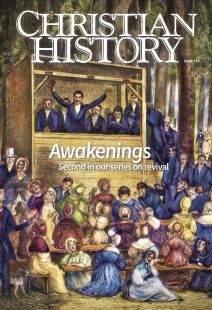

MM: Yes. We can see it as a series of concentric circles. Early evangelical awakenings (1730s–1740s) focused on salvation by grace and spiritual regeneration. Without abandoning this message, the Methodist movement centered on conversion and sanctification as a two-stage process. This second, larger circle, encompassed the first. And emerging from the Holiness movement was a healing revival. “Healing evangelists,” announced “salvation for the soul” and “healing for the body.”

Early Pentecostals affirmed everything prior, yet added a new message on the baptism in the Spirit, attested by speaking in tongues. Pentecostal revivalists called hearers to receive conversion, sanctification, healing, or Spirit-baptism. In contrast, evangelical revivalists in the 1800s and 1900s—Finney, Dwight Moody, Billy Sunday, Billy Graham—kept their focus on conversion. Holiness, healing, and Pentecostal messaging created a fork in the revival road. These supplemented the continued preaching for conversion.

The Black church has its own revival preaching tradition, described as “the Black folk sermon” or “old-time country preaching.” Black preachers dramatize biblical narratives and interweave them with contemporary anecdotes. This style still resonates deeply.

Q: What famous revival preachers should we know?

MM: Girolamo Savonarola (1452–1498), a Dominican who preached fiery repentance sermons in Florence, moved the people to hold a public “bonfire of vanities” and burn their luxury goods (see CH #149). Solomon Stoddard’s (pp. 6–8) periodic “harvests” foreshadowed later revivals. Theodore Frelinghuysen (pp. 22–25), a Dutchman in colonial New Jersey, offended his congregants by preaching that their drinking, gambling, and fighting displeased God, yet he succeeded in reviving many. Edwards famously preached “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” Gilbert Tennent preached boldly against sin, leading some to anger and others to faith. And the most famous, George Whitefield, could be heard without amplification by up to 20,000 people. The influence of these revivalists still echoes today.

Other notables included Hans Nielsen Hauge (1771–1824), a stalwart Norwegian revivalist and unlicensed preacher; he was imprisoned 14 times, yet established a revival movement. “Crazy” Lorenzo Dow (pp. 45–48), a frontier Methodist preacher, shocked his interracial audiences with stunts, such as smashing a chair to pieces as a sermon illustration. In contrast, Asahel Nettleton (1783–1844) represented a dignified, restrained approach, but consistently bore fruit over decades.

Women also filled the ranks of revival preachers, including Margaret Meuse Clay (1737–1832), the once enslaved “Old Elizabeth” (1766–?), and Harriet Livermore (1788–1868). All faced danger and scrutiny for preaching publicly.

In the twentieth century, which CH’s final issue in this revival series will cover, revival went global. William Seymour (1870–1922) was a Holiness preacher and leader of the Azusa Street Revival (1906–1909) in Los Angeles. Seymour’s congregation spread Pentecostalism internationally and was multiethnic and interracial so that “the color line was washed away by the blood [of Christ].” In her thirties, Maria Woodworth-Etter (1844–1924) became a Holiness revivalist and later embraced Pentecostalism. Billy Sunday (1862–1935) was a professional-baseball-player-turned-evangelist, colorfully saying he knew no more about theology “than a jackrabbit about ping-pong.” Mexican American revivalist Francisco Olazábal (1886–1937) preached in Mexico, Puerto Rico, and the United States.

John Sung’s (1901–1944) ministry rose meteorically across China and among Chinese expatriates, with many healings reported through his prayers. Aimee Semple McPherson (1890–1944) was a Canadian American Pentecostal leader and the first American woman with a radio license. Festo Kivengere (1919–1988) went into exile from Uganda during Idi Amin’s dictatorship, but stoked the East Africa Revival fires that began in the 1930s.

Bakht Singh (1903–2000) converted to Christianity, suffered family rejection, and became an energetic evangelist establishing hundreds of new congregations in India. Billy Graham (1918–2018), the best-known evangelist of the last century, was a key leader among international evangelicals. German-born Pentecostal Reinhard Bonnke (1940–2019) preached to the largest audiences ever. His preaching is said to have resulted in 79 million conversions, mostly in Africa.

Q: What will be the future of revivals?

MM: When Moody died in 1899, people said revivalism died with him. Yet the Pentecostal era was about to begin. Before Graham’s rise to fame in 1949, a Harvard scholar said revivals were a thing of the past. Instead of trying to predict whether, when, or how revival might come, it may be better to affirm that revivals remain—in Jonathan Edwards’s words—a “surprising work of God” that may exceed or contravene our expectations. CH

By Michael McClymond

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #151 in 2024]

Michael J. McClymond, is professor of modern Christianity at St. Louis UniversityNext articles

“The flame spread more and more”

A firsthand account of the revival at Cane Ridge

Colonel Robert PattersonDivine disruption

Healing revivals of the nineteenth century fueled later Pentecostalism

Charlie Self