“Music, Poetry, Art, through which God breathes”

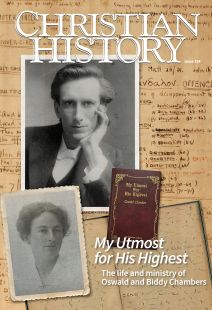

[Above: G. K. Chesterton, studio portrait (c. 1910), from the personal collection of Kevin Belmonte]

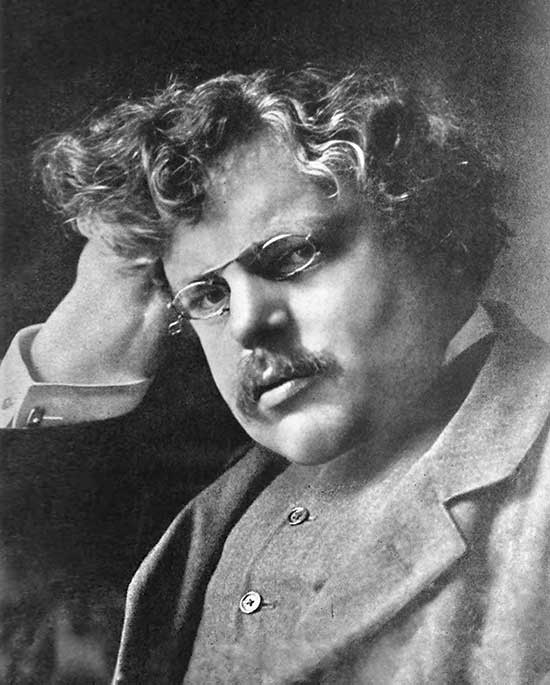

May 1997. A young recording artist, in London for sessions at Abbey Road Studios, knocked at the door of a private London home. An elderly lady of grace and poise opened the door. As she welcomed him inside, he told her how meaningful their visit was: “This, you have to know, is the highlight of my journey here.”

Smiling at her guest, the woman replied: “Oh, I’m very pleased. It’s lovely to meet you.”

This was how Steven Curtis Chapman, famed contemporary Christian singer-songwriter, remembers his meeting of Kathleen Chambers (1913–1997), then 83, the daughter of Oswald Chambers. And as he shared in this remarkable story, the visit would open a unique window into the artistry of her father.

Chapman and Chambers walked into her living room, where he saw something wholly unexpected: several fine seascapes and a framed charcoal portrait.

“That’s Beethoven,” Chambers said, “which [my father] did when he was 19. He set a mark on there. If you look, you’ll see it—on the right-hand side.” So Chapman saw the artist’s emblem Oswald Chambers created: the letters OC, set together, much like a mariner’s compass.

“It was incredible,” Chapman remembers, continuing:

I had no idea what I was going to experience. It was world-class artwork. It literally took my breath away. This was so important for me—this man who inspired me so much, and inspired millions with his life and his writings. I was seeing something that he created himself. For me, it was sort of like looking at the Mona Lisa.

So one storied hour unfolded, in moments of hospitality and memory, over English tea. Then, as Chapman recalls,

we said our goodbyes, and I went back to the work that I was doing there. We were doing some recording at Abbey Road Studios, which everybody in the music world would know, where The Beatles made records. But for me, it was like—“Yeah, that’s cool—but you know what’s really cool, I met Oswald Chambers’s daughter.”

That visit became all the more meaningful as just 10 days later, Kathleen Chambers passed away.

“I was able to capture that little moment right at the end of her earthly journey, to remember her father, and the amazing work that God did through him, and through her.” And what is more, Chapman had the chance to tell her: “I’m one who uses the arts to communicate the gospel message. And it’s so influenced by your father’s writing.”

On canvas and with the pen, Oswald Chambers’s gifts speak across the years.

REDEEMING ART

Early on Chambers’s artistic abilities flourished. He played piano with considerable skill, and his performances (though not as frequent as those who knew him wished) were memorable. Esdaile MacGregor, a friend of Chambers, said he was known “for his love of walks among the hills,” but also

for his interest in literature, and appreciation and knowledge of good music. I especially remember one night, which for me was epoch-making, when he played to me the Slow Movement of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata, and then read Tennyson’s Maud.

But while all this was true, it was Chambers’s great ability as an artist that family and friends remembered most. To develop his gift, he attended the Art School in South Kensington, England, and after, the University of Edinburgh.

At 18 Chambers obtained an “Art Master’s Certificate, enabling him to teach and illustrate and thus earn a livelihood.” His time at the easel then, painting and drawing, let his gift take wing. He “won a scholarship for two years’ travel to the famous art centres abroad.”

Yet telling as this was, he declined the honor held before him. From personal experience he’d seen and heard of others who had self-destructed during their studies.

Decadence and profligacy were common in the European art world of the 1890s. Chambers once said in a letter, “the spirit of art is to so sad an extent, the spirit of immorality.” As a person of deep faith with a love of the arts, Chambers cared greatly about “proving Christ’s redemption for the aesthetic kingdom.” It was, one might say, his credo, or the raison d’être for his art.

He knew of many great artists who were devout in faith, and prior to following a call to pastoral ministry, he wished to be an artist in the tradition of soli deo gloria (glory to God alone), as Bach wrote so often upon the manuscripts of his music. Chambers saw profound meaning in art, writing once of “Music, Poetry, Art, through which God breathes / His Spirit of Peace into the soul.”

Moreover, Chambers drew inspiration for artistic guides from his reading. In Shade of His Hand¸ Chambers wrote:

In Shakespeare’s writings there is an under-current of faith, which makes him the peculiarly valuable writer he is; and makes him more at home to those who understand the Bible point of view. . . .

But of all the poets Chambers read, Robert Browning (1812–1889) was the one he read most. It’s here Chambers is most clearly Victorian: in literary sensibility and indebtedness. At Dunoon College, training for pastoral ministry, Chambers did that most Victorian of things: he “started a Browning Society, and got students and some of the town folk to become enthusiastic readers of Browning’s poetry.”

“Robert Browning,” he wrote, was a “grand manly thinker.” And in a letter from Dunoon he said:

You will be glad to know that I have all Browning’s Works. . . . They were a kind of payment for a portrait I did . . . they are indeed a treasure to me.

Another Victorian writer Chambers read continually was his fellow Scot, novelist and poet George MacDonald (1824–1905). “I am reading Geo. MacDonald’s There and Back,” he wrote in 1907. “[He] appeals to my bias. I love that writer.” A second passage echoed this, but with a dash of Chambers’s infectious, gently subversive wit, that had a Dickensian flavor to it: “[T]here is a passage in Geo. MacDonald’s Marquis of Lossie that gives me pure chuckles of joy, it is such a ‘wipe out’ of the sounding piousness of humbug.”

Chambers continually referenced poetry to convey his points. In one 1912 booklet, The Discipline of Suffering, just 47 pages long, he cites poems of four lines or more 22 times.

Poetry was an artistic staple of Chambers’s teaching, and he often included “prose poems” from his own pen. Two passages, set as if in verse, show this—

(1) His cross

is the centre of Time and Eternity;

the answer to all the enigmas of both.

(2) . . . the old song,

from the ancient pilgrim’s song book,

has this thorn

at the heart of its suffering. . . .

Then too, if Chambers was thoroughly Victorian in his great love for Browning’s verse, his admiration for G. K. Chesterton’s (1874–1936) 1905 essay on the Book of Job, “Leviathan and the Hook,” showed Chambers was also Edwardian in outlook and sentiment, like Chesterton. Fascinatingly, both Chesterton and Chambers were born in the same year, indeed within two months of each other—Chambers on July 24, 1874, and Chesterton on the 29th of May. With appreciation Chambers read his contemporary’s books, memorably describing him as “that insurgent modern writer, Mr. G. K. Chesterton.”

COMFORTED WITH CONUNDRUMS

In The Discipline of Suffering, Chambers moved beyond Victorian conventional thinking when he praised Chesterton’s innovation, distinctiveness, and helpfully subversive way of writing in “Leviathan and the Hook.” He appreciated Chesterton’s approach that made it easier to see a classic text with new eyes, writing:

G. K. Chesterton in his individual, sufficient way, writing on Job, says—

“But God comforts Job with indecipherable mystery, and for the first time Job is comforted. Eliphaz gives one answer, Job gives another answer, and the question still remains an open wound. God simply refuses to answer, and somehow the question is answered. Job flings at God one riddle, God flings back at Job a hundred riddles, and Job is at peace.

“He is comforted with conundrums.”

Reading this, one might well think it is a reflection from Chambers, set within the pages of My Utmost For His Highest; but that it is Chesterton, cited with approval from Chambers, shows the kindred thought of both men.

Of all the recollections of Oswald Chambers that survive, perhaps the most discerning is this, written by Mrs. Duncan MacGregor, wife of the principal at Dunoon College:

How can Oswald Chambers be condensed into anything like a readable reminiscence? He was not one man, but many men. There is no label that one can attach to him and be satisfied—artist, poet, philosopher, preacher and teacher…

[But] I see him first as artist.

There is much truth here. And indeed, it was an artist who spoke these words, “There are many ways in which a man’s life may be suddenly struck by an immortal moment. . . .” CH

By Kevin Belmonte

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #154 in 2025]

Kevin Belmonte is the author of many biographies on figures in Christian history, including Defiant Joy: The Remarkable Life & Impact of G. K. Chesterton.Next articles

Serving God here and “Beyond”

Oswald and Biddy’s transformational ministry in Egypt

Annalise DeVriesBaffled to Fight Better

During the spring of 1917, Chambers spoke nightly on the book of Job

Oswald Chambers