Crossing barriers

[Above:Worshipers at Yoido Full Gospel Church for World A/G Congress 1994—Flower Pentecostal Heritage Center]

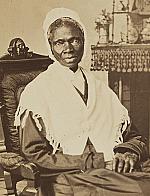

A humble, devout, and soft-spoken Black man from the Louisiana bayou, William J. Seymour (1870–1922) led a revival in Los Angeles that crossed racial, religious, and social boundaries. He invited people to experience the baptism with the Holy Spirit and spiritual “sign gifts” like speaking in tongues, healing, working miracles, and prophesying. The movement began on Azusa Street, in the former Stevens African Methodist Episcopal Church. After a fire destroyed its steeple, the building had been transformed into a barn with a pat dirt floor and apartments on the second story. What happened here in the fall of 1906 sparked curiosity around the nation and the world, and it changed the fabric of Christianity for the next century and beyond.

William J. Seymour was born to the formerly enslaved Simon and Phyllis Salabar in Centerville, Louisiana, on May 2, 1870. He and his seven brothers and sisters attended a local Catholic church and later a nearby Baptist church. In the 1890s, like thousands of other southern Blacks, he traveled north along the routes of the former Underground Railroad and lived in Memphis, St. Louis, Indianapolis, Cincinnati, and elsewhere. At the all-Black Simpson Chapel Methodist Episcopal Church in Indianapolis, he became a born-again Christian.

During this time Seymour was influenced by Daniel S. Warner’s (1842–1895) Evening Lights Saints, later called the Church of God Reformation Movement. This radical Holiness group promoted racial equality and reconciliation at the height of Jim Crow segregation and regularly evangelized and served in the Black community. After a bout with smallpox left Seymour blind in one eye and with pockmarks on his face (which he covered with a light beard), he responded to God’s calling on his life and was ordained an evangelist by the Evening Lights Saints.

Saints and speaking in tongues

In 1905 Seymour moved to Houston where he met a preacher named Charles Fox Parham (1873–1929) and attended his Houston Bible School for a short time. There Seymour was asked to respect Texas segregation laws by sitting in the hallway or an adjacent room. After soaking up Parham’s teaching that speaking in tongues is the initial, physical evidence of the baptism with the Holy Spirit mentioned in the Bible (Acts 1:5 and elsewhere), Seymour joined Parham in conducting evangelistic work in the local Black community for a short while.

Seymour arrived in Los Angeles on February 22, 1906, to pastor a mission being led by Julia Hutchins. Considering his preaching about speaking in tongues unbiblical, Hutchins expelled Seymour from the mission on March 4. On April 6 Seymour started a 10-day fast for revival at Richard and Ruth Asberry’s home at 214 Bonnie Brae Street. The prayer meeting he started there erupted into a revival that outgrew that home and relocated to the church-turned-barn at 312 Azusa Street, in the Black section of Los Angeles. Soon the meetings were attracting upwards of 1,200 people per night. The services generally ran three times per day for three years straight from 1906 to 1909, with thousands attending, many from far away.

Though the Azusa Street Revival featured unity of spirit for much of its duration, there were setbacks. Betrayal and schism undermined Seymour’s spiritual authority and ability to influence the global Pentecostal movement after 1911.

Despite these setbacks the revival attracted a large number of clergy, pastors, evangelists, missionaries, and Christian workers seeking spiritual renewal. Many of them returned to their homes or went overseas to spread the message. In addition the fledgling Pentecostal movement spawned daughter missions in many areas, and there were 405,000 copies of its Apostolic Faith newspaper circulating around the world. All of this helps to explain how, by 1915, Azusa missionaries had spread the Pentecostal Revival to more than 50 countries around the world and almost every town in the United States with a population over 3,000.

The teaching at Azusa

The most distinctive qualities of Seymour’s revival were its emphases on having a personal conversion experience with Jesus Christ; being baptized with the Holy Spirit; the practice of the spiritual gifts listed in 1 Corinthians 12 and 14; a focus on spiritual renewal, divine healing, spiritual warfare, and exorcisms; powerful, enthusiastic worship; lengthy services; times of prayer and meditation; and commitment to evangelism, missions, and evangelistic social work. In an effort to nurture and disciple followers, Seymour also provided regular spiritual guidance and mentorship through letter writing, personal visits, his newspaper, and preaching tours across the United States.

The revival attracted women, immigrants, the poor, the handicapped, and the working class—but also some from upper-class backgrounds. Seymour created a Christian social space that defied the unbiblical social conventions of the day, such as segregation and racial discrimination, where Christians could cross religious, racial, class, educational, and other boundaries. As one woman who attended those services as a child reminisced later, “It didn’t matter if you were black, white, green or grizzly. There was a wonderful spirit. Germans and Jews, Blacks and Whites, ate together. . . . Nobody ever thought about color.”

Seymour and his Azusa Street leadership team created a theology of divine healing based on Jesus’s victory over sin, sickness, and death. They taught that all of the spiritual gifts practiced in the New Testament church are available to all born-again, Spirit-filled believers today—including the spiritual “sign gifts” of speaking in tongues, divine healing, miracles, and prophecy (1 Cor. 12; Mark 16:15–20). Unlike most Protestants of their day, early Pentecostals believed that the spiritual sign gifts did not cease with the death of the apostles, but are fully available today to all who would ask in faith. They based this belief on John 14:12, where Jesus said that whoever believes in him will do even greater works, and on the Great Commission in Mark 16:15–20, where Jesus called on his followers to preach the gospel around the world with signs and wonders, such as placing their hands on and healing the sick.

At Azusa Street, the threefold purpose of divine healing was to bring relief to the person suffering from the illness, to attract the lost and backslidden, and to serve as a concrete sign and symbol to the unbelieving world of God’s miraculous power. Sin and sickness were not limited to physical ailments, but also included emotional, spiritual, and psycho-societal ones—including racial prejudice.

Body, soul, and society

The teaching of racial unity was a huge contributor to the movement’s rapid growth across the United States (especially among racial-ethnic minorities) and around the world (especially in countries of the Global South, many of which were dominated by European colonial empires). Divine healing and miracles played a critical role in Pentecostal expansion as well, not only because they brought relief to broken bodies and spirits, but also because Seymour and his followers used them to address unbiblical racial-ethnic divisions. He argued that the outpouring of the Spirit fell on all people around the world—irrespective of their race—and united them into one body of believers whose Holy Spirit baptism gave them a common experience, purpose, mission, and goal, which was to help usher in the Second Coming of Jesus Christ by evangelizing every nation.

These early Pentecostals invoked biblical precedent for racial unity, citing the stories of the Samaritan woman (John 4:4–26), the Roman centurion (Matt. 8:5–13 and Luke 7:1–10), the Syrophoenician woman (Mark 7:24–30), and the Ethiopian eunuch (Acts 8:26–40), as well as Paul’s ministry to the Gentiles, including his rebuke of Peter’s Jewish ethnocentrism (Gal. 2:11–20). They also interpreted the Day of Pentecost in Acts 2:4 as an appropriate image of how Jesus’s followers from around the world had gathered together despite linguistic and national differences. They pointed out that Jesus and his disciples often crossed social boundaries to help people who were sick, marginalized, demonized, and suffering.

At the height of Jim Crow policies in America, Seymour’s newspaper, Apostolic Faith, boldly declared, “God recognizes no man-made creeds, doctrines, or classes of people, but ‘the willing and the obedient.’” The paper also affirmed that “no instrument [of God] is rejected on account of color” and that “one token of the Lord’s coming is that He is melting all races and nations together. . . . He is baptizing by one Spirit into one body and making up a people that will be ready to meet Him when he comes.”

Despite the fact that racial division did later arise in some sectors of the movement around the world, Seymour’s original vision of a unified, race-defying community has remained a major impetus behind the movement to this day. In this respect the Azusa Street Revival’s message foreshadowed the later message of Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, which created a similar faith-based intersectional theology that sought to liberate people of all races and classes suffering from unbiblical social divisions.

The first Pentecostals recognized divine healing and miracles as distinct but interrelated gifts of the Holy Spirit and almost always talked about them together, sometimes even interchangeably. They believed divine healing should be a normal part of the Christian life. Seymour taught that one of the three key duties of a pastor, after preaching and meeting with members of the church for spiritual formation, was to visit the sick, and when the opportunity arose, to pray for healing. He and his followers at first thought Christians should avoid medicine and simply pray for divine healing, although they modified this view very early in the movement and encouraged people to first anoint and pray for the sick and then take medicine if and as needed. Seymour wrote: “The Lord never revoked the commission he gave to his disciples: ‘Heal the sick, cleanse the lepers, raise the dead.’”

A driving force

Today the Azusa Street Revival’s message of divine healing remains a driving force in the growth and development of the Pentecostal/Charismatic movement around the world. The movement that Seymour shaped had blossomed to 644 million people; 19,300 denominations; and 1,336,000 congregations around the world by 2020. Some scholars project that by 2050 there will be one billion Pentecostal/Charismatic Christians. CH

By Gastón E. Espinosa

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #153 in 2024]

Gastón E. Espinosa is the Arthur V. Stoughton Professor of Religious Studies at Claremont McKenna College and the author of nine books including William J. Seymour and the Origins of Global Pentecostalism and Latino Pentecostals in America: Faith and Politics in Action.Next articles

Azusa Street commentary and excerpts

The Azusa Street Revival won hearts amid criticism

Michael J. McClymond and othersWhen the Spirit moves: CH153 Gallery

A diverse collection of revivalists from the 1800s and 1900s

Charlie Self