A durable spirituality

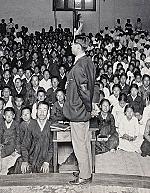

[Above: John Sung, mid-20th Century. From The Diary of John Sung, Genesis Books, 2012—Public domain, Wheaton College Special Collections]

The most famous revivalist in Chinese history traveled farther, preached more often, and brought more people to Christ than any other. In his 12-year career, John Sung (Song Shangjie, 1901–1944) logged more than 100,000 miles, usually preaching at least three times a day. Through his revival meetings, more than 100,000 people prayed for new life. By one accounting at least 10 percent of all Chinese Protestants in the world had been born again through his ministry. In the forge of his “hot and noisy” revivals, where singing mixed with confession, laughter with groans and tears, Sung hammered out a Christian spirituality for Chinese people that proved durable through social upheaval, war, and revolution.

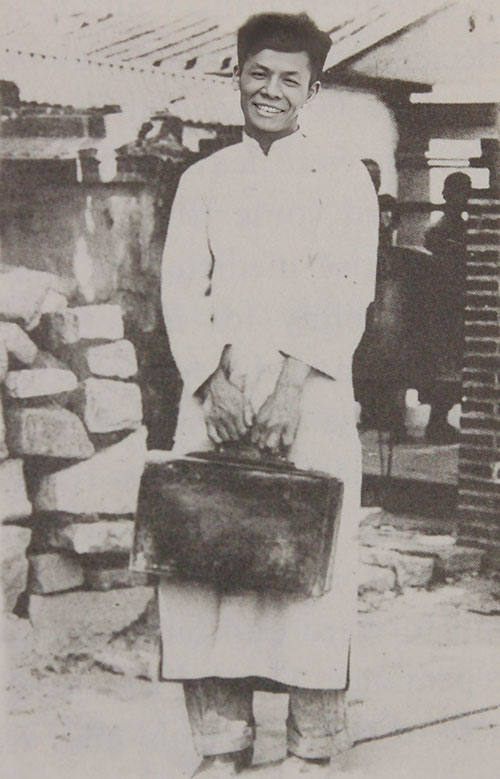

Few people could have been a more unlikely tool in the hands of God. Sung grew up in a Christian home in the Chinese coastal province of Fujian where, as the son of a Methodist pastor, he zealously joined his father in ministry. But while studying at Union Theological Seminary in New York, Sung had a mental collapse. He spent 193 days in an insane asylum, imagining secret messages sent to him in New York Times crossword puzzles, using a special dictionary that Jesus supposedly gave him to translate the Gospel of Mark into a design for a radio to pick up heavenly broadcasts, and marrying Mary, the mother of Jesus, in his hospital room. The doctors finally released him, not because he recovered, but because Union could no longer afford his care. Forced to return to China, Sung still struggled with delusions.

A new conviction

Confused, Sung sought a new direction for his life. Could he teach science? Perhaps, but it would require that he convince the schoolmaster of his sanity. In conversations with W. B. Cole, who oversaw Methodist education in Fujian, Sung found something better than a job. Despite all the chaos of his New York experience, Jesus Christ was still there. When the Lord, rather than arcane messages or heavenly weddings, became his central focus, everything else became secondary—even disposable. Sung was no longer under the power of mental illness, but healed by Jesus who became the integrating presence and force of his life.

Having found Christian language to convey the drama of his transformation, Sung received invitations to preach. None was bigger than the request to address the 1931 National Christian Council’s second meeting on revival held in Shanghai. Sung used his less prominent timeslot to convey the mysteries of Genesis 1: the seven days of creation held the secrets to the first seven chapters of the Gospel of John, the seven stages of church history, and the seven steps of his own spiritual journey from darkness to rest. Such sermons were still not typical revival fare, dabbling in curiosities rather than pushing for confessions, but the cofounders of the Bethel Mission, Jennie Hughes (1873–1951) and Shi Meiyu, also known as Mary Stone (1873–1954), saw potential and invited Sung to travel with their newly formed Bethel Worldwide Evangelistic Band (BWEB), a team of five men who led revivals throughout China.

Sermon on the spot

Sung took to Bethel’s revivalism immediately. Within a couple of hours, people could discover they were lost, encounter the life-giving presence of Jesus Christ, and leave reborn. No one was better at moving people through that three-step process than John Sung. In fact he became so proficient that he could invite the audience to shout out a Bible chapter for him to preach from, and he would concoct a sermon on the spot.

Sung was especially ruthless in his conviction of sin, trampling social taboos by asking if anyone had fornicated—and then making everyone squirm by getting specific: “Did you almost? Mentally? Who has committed this sin?” He paused, waiting, until finally someone indicated that he or she had been sexually impure. Then another and yet another raised their hands in confession. On and on it went, men and women weeping with remorse until Sung was satisfied that sexual impropriety had been fully disgorged. Then he would ask another question: “Who has hated?” Sung could grind through the ins and outs of 30 or 40 sins in one sermon, insisting people acknowledge the grip sin had on them.

It was the necessary prelude for what came next. At the end of the sermon, Sung would invite all those ensnared by sin to come to the front to meet Jesus. They now had a role to play in a drama that had eternal consequences. People could choose to stay seated, evidence that they were paralyzed by sin and resistant to God’s mercy, or they could get up, separate themselves from their old life, and go to their Savior.

At the altar familiar social categories were erased. Clergy mixed with laity; men, women, and children intermingled as equals. They articulated their failures out loud, usually with tears. Something new was born in that socially porous moment, something very different from the hierarchical life that characterized the Chinese church, home, and work. The effect was profound.

Many churches in China ached for such a freeing experience. In two years Sung and the BWEB covered more than 15,000 miles; held 1,199 revival services; and spoke to 425,980 people as churches begged for their services. In 1933 the BWEB broke up, and Sung went solo.

City light

His revivals were almost always in cities. People who worked in department stores or banks or went to school had something not available in the countryside: free time. Depending on their schedules, urbanites could at least attend a morning, afternoon, or evening service. Plus Sung’s presentation of the gospel gave new meaning to their leisure. Instead of squandering it on movies and picnics, he told them to organize into evangelism teams. Each person was to contribute something, so the group could buy tracts or provide bus fare to take the gospel to others. Their obedience was not just necessary for their salvation, it also gave them a meaningful role in God’s plan. Their preaching would usher in the victorious return of Christ.

New women

The women of China were the most enthusiastic about this opportunity. For millennia they could only be daughters, wives, and mothers. No other roles were open to them. In teams, though, Sung required a leader, a secretary, a treasurer—and everyone was an evangelist. “The Lord saves men, and also saves women,” Sung preached. “This is true gender equality.” For many Christian women, Sung’s revivals provided a pathway to modernity and allowed them to assume the title of “New Women”—a popular term for those who dared to break with tradition to lead China into a better future.

Deliverance from sin also meant freedom from sickness, so Sung held healing services, sometimes praying individually over 1,700 people a day. Miracles multiplied wherever he went. Some worried that his healing overshadowed his spiritual work, but Sung never saw them as distinct. Jesus, he insisted, saves the whole person.

As his fame spread, and the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) made it difficult for him to work in mainland China, Sung took his revivals to Southeast Asia. He began to speak publicly about spreading revival fires from India to Africa, and then in the West. However, his aspirations were cut short by his disintegrating health. In December 1939 Sung preached his last sermon from a cot in Indonesia. He never recovered, dying five years later in a cottage outside Beijing.

A few years later, the one million Protestants in China began to face persecution. By 1970 Jiang Qing, an instigator of the Cultural Revolution, pronounced religion in China dead. It was one of the greatest exaggerations in history. Christianity was not dead, but spreading. China has 100 million Protestants today.

Ongoing miracle

It’s apparent that the Chinese church absorbed key features of Sung’s revivalism. For example ordination was irrelevant for Sung and his evangelistic teams. What mattered was the power given by the Holy Spirit to preach with boldness. Thus the government’s efforts to limit ordination did virtually nothing to slow the spread of Christianity. Likewise healing was now an integral part of Chinese Christianity. In some places up to 90 percent of converts testified to the role of a miraculous cure in their conversion.

Finally, the emphasis on evangelism remained strong. Christianity has grown 50 times faster than the general population over the last 75 years. Women have been especially effective in evangelizing their social networks, but almost all Chinese believers understand that to be a Christian is to be a witness. Sung’s insistence that sharing the gospel with others is a necessary part of salvation has produced a kinetic Chinese Christianity that pulsates with revivalistic fervor today. CH

By Daryl R. Ireland

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #153 in 2024]

Daryl R. Ireland is the author of John Song: Modern Chinese Christianity and the Making of a New Man. He is a professor of mission at Boston University and the associate director of its Center for Global Christianity and Mission.Next articles

Century of the Holy Spirit

Pentecostal, Charismatic, and Third Wave Revivals of the Twentieth Century

Connie Dawson