Utmost ongoing

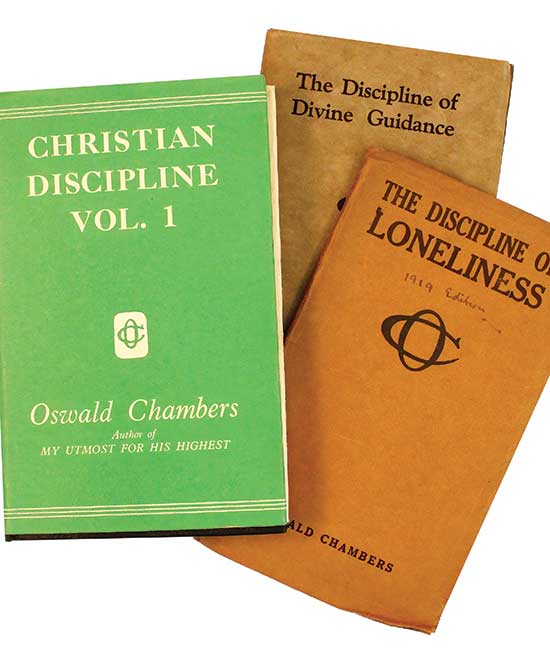

[Above: Oswald Chambers: Christian Disciplines, Vol. 1, Marshall, Morgan & Scott, 1965; The Discipline of Loneliness, The Complete Press, 1919; The Discipline of Divine Guidance, Simpkin Marshal, 1933 to 1935—Photos by Max Pointner / Wheaton College Archives and Special Collections]

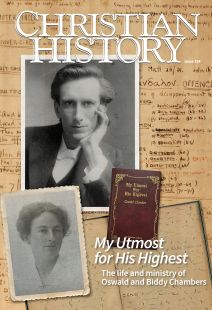

Macy Halford is the author of My Utmost: A Devotional Memoir and the curator and editor of the OCPAL-authorized Modern Classic Edition of My Utmost for His Highest. We spoke to her about Oswald Chambers and his famous devotional’s impact, both personally and generally, over the years.

Christian History: Tell us about how you became acquainted with Oswald Chambers and his works. How have his life and writings influenced and inspired you personally?

Macy Halford: I got my first copy of My Utmost for His Highest from my grandmother when I was 15. I started reading it daily not long after. Then I kept reading it, over and over again, for years (now decades!).

I think of Utmost as a refrain that calls us back, again and again, to certain essential truths. The most notable, for me, is the truth that God is in control of every aspect of our lives. That might sound like nothing original, but in Chambers’s hands, it becomes an entire philosophy, or mode of living: God is in control of every minute of our lives; he has commanded us not to worry; and he expects us to abandon ourselves to his will, day by day, minute by minute. This is the discipline of faith. When we commit to living in this way—continually abandoning ourselves to his will—we are free.

Chambers wrote often on this theme, but he also put it into practice in his own life. So I suppose I find his life and work inspiring for exactly the same reason.

CH: Do you have a favorite devotional or other work by Chambers? What is it and why?

MH: I love the two volumes of Christian Disciplines. Like all of Chambers’s published books, the essays in these volumes originated as spoken messages, but unlike most of his books, which were edited and published posthumously by Biddy, they were edited by Chambers himself. They really show what kind of thinker he was. Each essay is based in Scripture, but also incorporates bits of poetry, philosophy, hymns, and essays by popular writers.

What I love about the Disciplines is that they allow you to get into the Chambers groove. It isn’t always obvious in Utmost, which is comprised of very brief excerpts, but Chambers was a highly kinetic speaker. He never used notes or outlines when he preached; he just spoke as the Spirit moved him. I imagine this is also how he edited Christian Disciplines: the citations are woven in a bit wildly, and the whole thing has a flow to it that makes it feel alive.

There’s a meta quality to all of Chambers’s work that’s most evident in the Disciplines. The subject of his work—abandoning oneself to God and the Spirit minute-to-minute, second-to-second—is also how his work was produced as well as an indication to the reader of what kind of work it is: a spiritual document.

CH: Many Christians are familiar with My Utmost for His Highest (MUFHH) but don’t know much about the man behind it. Why do you think that is the case?

MH: I think this was a purposeful choice, first on Chambers’s part and then, following his death, on the part of his wife. In essence their philosophy was: not me, but God in me. Chambers often preached on John 3:30: “He must increase, but I must decrease.” He was wary of becoming what he called “an amateur providence,” someone who took the place of God in someone else’s life.

Biddy, his wife, was even more extreme in her desire to remain unknown, even abandoning her birth name, Gertrude. Her nickname “Biddy” describes how she saw herself: as a person defined by her relationship to the Person she served, not by anything in her self. She aimed to live the life “hid with Christ in God.”

Now, of course, there are multiple biographies of both Biddy and Oswald. I’m not sure what they would make of this! But when you are the author, or coauthors, of a book that has has been a bestseller for decades, you’re going to have a little light shone on you. I imagine they’d say it’s fine—as long as the light ultimately shines through them onto the cross.

CH: How important was Biddy Chambers to the formulation and publication of My Utmost for His Highest?

MH: It would be hard to overstate the scope of Biddy’s accomplishment with Utmost. For a decade after Oswald’s death, she’d been producing books and pamphlets from her own shorthand notes of his sermons. But none of these early efforts had met with much success, probably because, printed verbatim, Chambers’s sermons and lectures were difficult to parse; certainly they were very, very long. Perhaps they were engaging as spoken word, delivered by Chambers (a reportedly charismatic speaker), but they didn’t quite work as printed books.

So what Biddy accomplished with Utmost is pretty amazing. She hit upon a format—concise, thematic readings, anchored by a Bible verse—that finally allowed Oswald’s message to resonate with a large audience.

CH: What impact do you think MUFHH had on believers when it was first published?

MH: Utmost’s first surge in popularity came with the Second World War, in part because it was known as a war book. Some of its excerpts had been taken from sermons Chambers preached to soldiers stationed in Egypt during World War I, and these spoke to what people were experiencing in the 1940s.

In terms of content, there’s a heavy strain of realism, focused on the problems of sin and why God allows suffering, which runs throughout Chambers’s work and makes it a natural fit with the Christian Realism movement that began in earnest in the 1930s. Reinhold Niebuhr published Moral Man and Immoral Society in the United States in 1932; Utmost appeared in the United States in 1935.

There are crucial distinctions between Chambers’s work and the work that came out of that movement. Chambers was never overtly political or concerned with international relations, for instance. But I think Utmost’s initial impact and sudden success can be understood in view of the Realism movement’s critique of Protestant churches before World War II: they saw a weak, naive, and utopian Christianity preached that failed to address suffering. Chambers lodged the same complaints at churches in his own prewar era.

For a readership grappling with the rise of Hitler and Mussolini, realism about sin and evil was actually quite comforting. When I think of Chambers, the phrase “cold comfort” comes to mind.

CH: What are the critiques this devotional has received over the years? How do you respond to those critiques?

MH: It has been critiqued for its realism and for what some see as an overly pessimistic view of humanity, its emphasis on negating the self in favor of Christ-realization. Alternately, it has been criticized for emphasizing an individualistic faith, rather than a community-oriented faith (though I think this critique is simply without merit). And its message on sanctification has drawn fire. But by far the most common critique is that it’s difficult to understand.

First I’d respond that Utmost is only an entry point to the rest of Chambers. He was a student of philosophy, psychology, and theology, and his sermons are works of philosophy, psychology, and theology. Their full meaning can be glimpsed in Utmost, but not grasped entirely.

Second—and this is a defense I love to mount, and which I develop at length in my memoir—is that Chambers’s thought is difficult to follow on purpose. He took his cue from John 3:8: “The wind bloweth where it listeth, and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh, and whither it goeth: so is every one that is born of the Spirit.” Essentially he thought that the Spirit was inherently unpredictable and that those following its dictates (those who had the Spirit dwelling inside them) were impossible to pin down or predict. Chambers never wanted to be intellectually pin-downable; his friends called him the “Apostle of the Haphazard.”

Finally I’d respond by saying that Utmost’s complexity has clearly worked in its favor. It gives readers a lot to think about.

CH: How do you think MUFHH can speak to the world today?

MH: Utmost is timeless. Even if Chambers’s initial audiences were soldiers in wartime and, before that, missionaries in training, his words speak to the struggles we all face, day to day. Chambers had a keen sense of human nature and human psychology and a deep understanding of what the Bible has to say about human nature. Any work that takes these as its themes will never be out of fashion. CH

By Macy Halford

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #154 in 2025]

Macy Halford is the author of My Utmost: A Devotional Memoir and the curator and editor of the OCPAL-authorized Modern Classic Edition of My Utmost for His Highest.Next articles

Recommended resources: Oswald Chambers

Discover the works, lives, and ministries of Oswald and Biddy Chambers and others in these resources recommended by our authors and the CH team.

the editors and authorsQuestions for reflection: Oswald and Biddy Chambers

The lives and legacies of Oswald and Biddy Chambers

the editors