How to speak “Mercersburg”

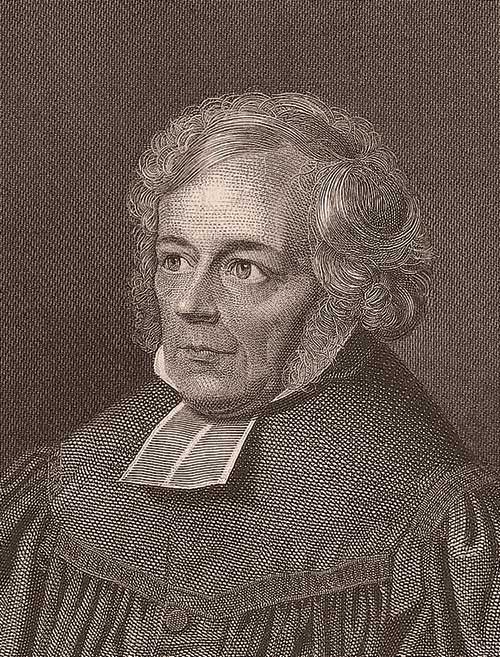

[Above: Friedrich Leonhard Lehmann, Portrait of Friedrich Ernst Daniel Schleiermacher, Nineteenth Century. Steel engraving—Public domain, Rijksmuseum]

Understand the philosophies and philosophers that influenced the Mercersburg movement with these handy definitions.

DEFINING TERMS

Evangelical catholicism—a term that arose in the context of nineteenth-century efforts to retrieve more creedal, sacramental, and liturgical dimensions from the historical Great Tradition (sometimes called “small-c catholicism”) that had informed classical Protestantism.

New Measures revivalism—an approach to revivals associated with the ministry of Charles Finney, which considered revivals something you could plan and prepare for rather than receiving as a sovereign gift of the Holy Spirit.

Scottish common sense realism—a form of British empiricism (the conviction that knowledge is based on sense experience) associated with Thomas Reid and Dugald Stewart, who responded to problems in David Hume’s radically empiricist philosophy. They viewed ideas not as mental objects that represent reality to the mind, but as acts of direct perception. These ideas are then processed according to assumed principles (the existence of material objects, the existence of the knowing self, cause and effect, etc.) that comprise the “common sense” that all humans possess. This philosophy prevailed in early America.

Idealism—a philosophy that goes back to Plato’s conviction that true knowledge is the contemplation of eternal Ideas or “forms,” such as the form of the human being in which all people participate. It holds that Ideas are foundational to reality and that the general has priority over the particular. Nineteenth-century German idealism responded to Immanuel Kant, who taught that reason can know things as they appear to us (phenomena) but not things in themselves (noumena). Hegel, however, argued that if reality is ultimately ideal and the unfolding of “Absolute Spirit,” then we can know it through reason after all. Hegel famously framed this process in terms of conflict between the “thesis” and the “antithesis,” which issues in a higher “synthesis.” Schelling often spoke of this historical development as the unfolding of living “organic” laws or principles.

Mediating theology—a diverse mid-nineteenth-century theological movement in Germany made up of Lutheran and Reformed figures, such as the church historian August Neander, and theologians, such as Julius Müller, Karl Ullmann, and Isaak A. Dorner (see pp. 38–41), that sought to keep the intellectual acheivements of Hegel and Schleier-macher alive while being faithful to evangelical Protestantism and Christian orthodoxy. In this way they synthesized or “mediated” between modern scholarship and the Christian tradition. Mercersburg can be viewed as an effort to apply the insights of the German mediating theology to the American religious situation.

PHILOSOPHICAL FRIEDRICHS

The Mercersburg movement drew some of its philosophical ideas from the well of nineteenth-century German thinkers: most significantly, philosophers George Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) and Friedrich Schelling (1775–1854), and theologian Friedrich D. E. Schleiermacher (1768–1834).

G. W. F. Hegel—among the most influential figures in German idealist philosophy. Hegel was an heir of the Enlightenment movement and a student of ancient philosophy and Christian theology. He critiqued and sought to address the epistemological problems introduced by Kant’s noumenal / phenomenal distinction. In his book, Phenomenology of Spirit, he argued that reality as we experience it is the dialectical (conflicting impulses that resolve in a higher synthesis) unfolding of Absolute Spirit, and that it can be known through reason. Hegel studied at Tübingen’s seminary, where one of his roommates was Schelling. His writings, famously difficult to decipher, nonetheless had a pronounced effect on German Christian thought, particularly the views of history, Christology, and God’s relation to the world.

Friedrich Schelling—an influential German idealist. Like Hegel, Schelling was interested in Greek philosophy and the early church fathers. However, their thinking later diverged in important ways. The two men would go on to criticize each other’s work, both publicly and privately, for the rest of their careers.

Friedrich D. E. Schleiermacher—a theologian, philosopher, and German Reformed pastor. As a contemporary of both Hegel and Schelling, Schleiermacher sought to answer Enlightenment and Romantic criticisms of Christianity in his 1799 On Religion: Speeches to Its Cultured Despisers. His later work especially addressed the problems for religion posed by Kant. While Kant had viewed Christ as a helpful teacher of moral truth, Schleiermacher contended in his systematic theology, The Christian Faith, that every aspect of Christianity is related to the redemption accomplished by Jesus Christ. And religion is best understood, according to Schleiermacher, as neither matter of reason nor ethics but as a “feeling of utter dependence.”

Today Schleiermacher is often depicted as the father of liberal Protestant theology, but for many in the nineteenth century he was a bridge from rationalism to orthodoxy. Philip Schaff wrote, “Schleiermacher first built a bridge over the abyss that divides the dismal swamp of skepticism from the sunny hills of faith and kindled again the flame of religion and of the Christian consciousness.”—editors CH

Terms defined here appear in color throughout the issue.

By the editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #155 in 2025]

Next articles

Editor’s note Mercersburg movement

John Williamson Nevin, Philip Schaff, and theology in Lancaster.

Kaylena Radcliff