Editor’s note Mercersburg movement

[Above: CH editor Kaylena]

If you’re at all familiar with Lancaster, Pennsylvania, probably the first thing that comes to your mind is its well-known Amish community, and the bucolic imagery their lifestyle conjures: miles of rolling farmland, horse-drawn buggies on country lanes, cows and sheep and chickens free-ranging in grassy fields. And you’d be right—at least about surrounding Lancaster County.

Lancaster itself, however, is a real city, one as historic as neighboring Philadelphia, and with the same fingerprints of colonial and revolutionary America all over it. During a recent visit, I went in search of some of that American history in Woodward Hill Cemetery.

On a blustery spring day, dragging my elementary school-aged children along after a two-mile trek, we entered the grounds most famous for housing the grave of the country’s fifteenth president, James Buchanan.

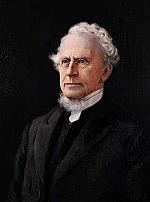

We’d get to Buchanan, I told them. First I was on the hunt for another grave, which was a bit less famous and a little more difficult to find. We kept our eyes peeled as we stalked the grounds. I only caught it thanks to a passing glimpse of the Chi-Rho symbol I knew should be there, but there it was: the final resting place of John Williamson Nevin.

Who?

Again those familiar with Lancaster probably don’t think “John Williamson Nevin.” Before editing this issue, I knew nothing about him. But the life and work of Nevin—a minister in the German Reformed Church, a scholar and theologian, and the architect of a nineteenth-century Christian philosophy known as the Mercersburg movement—have a greater bearing on American Christian history than you might realize.

In this issue you’ll meet Nevin and his fellow theologian, Philip Schaff, a scholar, historian, and minister in the German Reformed Church. Working first from a seminary located in Mercersburg, Pennsylvania, and later from college and seminary campuses in Lancaster, the Mercersburg thinkers challenged the zeitgeist of American Christianity in the nineteenth century by swimming against the tide of revivalism and its iconic practices.

They also developed, wrote about, and shared a particular vision for the church they encountered in the United States. Before ecumenism even existed as a concept, Nevin and Schaff imagined an impossible future: one in which Catholicism and Protestantism could find common ground, recover the good, and slough off the aberrant in both traditions. Such a position invited heated controversy and charges of heresy.

They desired to see a gathered worship that recovered ancient practices and a Christianity that centered the presence of Christ, namely, in its understanding of the Incarnation and the Lord’s Supper. Again controversy ensued as some saw their views as far too Catholic. But along with their students, the two thinkers defended their hopeful vision of a recovered and united Christendom for the rest of their lives, facing off against various factions—Charles Hodge and the luminaries of Princeton Seminary, Charles Finney and his fellow revivalists, and finally, influential leaders of the German Reformed Church.

A VISION OF A UNITED FUTURE

What came of these strivings might not be readily apparent, as America’s civil war eclipsed the movement’s discourse and influence. And yet as the twentieth century dawned, rife with greater evils outside the church than the conflicts within, the Mercersburg vision of Christian unity looked more appealing to believers both in the United States and around the world.

As I have had the opportunity to learn about the thinkers of this movement myself, I am surprised by the fingerprints I see in both my local Pennsylvania history and in theological thought throughout American Christianity. Like the unassuming but beautiful gravestone I found in Woodward Hill Cemetery (see p. 17), the ideas of Mercersburg are present but unnoticed.

Today as Christians seek to find their roots in the ancient church and interpret what that means for a common future, many are discovering the writings of Schaff, Nevin, and other Mercersburg thinkers for the first time. A Mercersburg revival might just be at hand. CH

By Kaylena Radcliff

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #155 in 2025]

Kaylena Radcliff is managing editor of Christian History