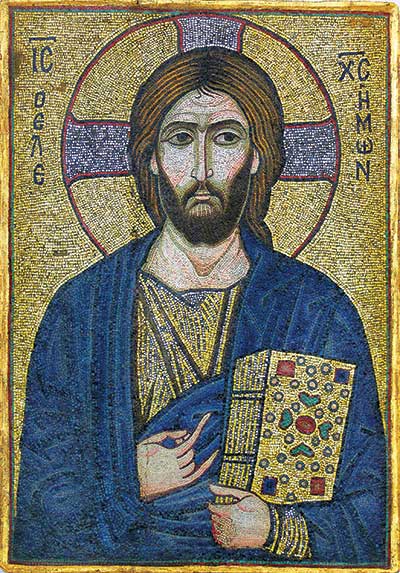

“The new creation in Christ”

[Christ the Merciful, Twelfth Century. Mosaic Icon, Byzantine—Photo: Andreas Praefcke, 2007 / Museum for Byzantine Art, Bode-Museum, Berlin / Public domain, Wikimedia]

In these excerpts from the January 1850 Mercersburg Review, Nevin argues against the American Protestant tendency to downplay the Incarnation and discount the real spiritual union between Christ’s incarnate humanity and the Christian.

But why should we go on to multiply proofs in this way, for what no unsophisticated reader of the New Testament surely will pretend to deny? What can the New Testament be said to teach at all, if it does not teach the fact of the mystical union, the true and actual formation of Christ’s life into the souls of his people? Men may get rid of this teaching, if they choose, by willfully turning the whole of it into barren metaphor and figure. But it is with a very bad grace they then turn round and say: We go by the Bible. . . .

The question of election, the question of the perseverance of the saints, and many other questions made to be of primary account in one orthodox system or another, are of far less clear representation in the Bible, than this view of the Christian salvation as involving “Christ in us the hope of glory.” Nor is it, by any means, of new acknowledgment in the Church, however strange and transcendental it may now sound to some “evangelical” ears. It runs through the universal theology of the old Christian Fathers. It forms the key-note to the deepest piety of the Middle Ages. It animates the faith of all the Reformers. Luther and Calvin both proclaim it, in terms that should put to shame the rationalism of later times, pretending to follow them and yet casting the mystery to the winds.

NO PASSING REVELATION

The Jewish dispensation had respect to the wants of the universal world, and was intended from the beginning to make room for the coming of Christ; which took place, accordingly, at last, when the “fullness of the time was come” (Gal. 4:4), “in the wisdom of God” (1 Cor. 1:21), and “according to the riches of his grace, wherein he hath abounded, toward us in all wisdom and prudence” (Eph. 1:7–10). The Incarnation, in this view, was no passing theophany [visible manifestation of God] or avatar. It was the form in which the sense of all previous history came finally to its magnificent outlet. This outlet, however, when it did come, involved a great deal more than was comprehended in the actual constitution of the world, the living human world, as it stood before; for it was brought to pass by the real union of the everlasting Word with our fallen life.

The mystery of the Incarnation had been coming through 4,000 years; still the coming was not the presence of the fact itself; as little as the aurora which gilds the eastern heavens may be taken for the full orbed splendors of the risen sun. Christ is the sense of all previous history, the grand terminus towards which it was urged from the beginning. . . . He is the true basis thus of the period going before, as well as of the period that follows.

HE MUST BE ALL

Two conceptions, in this way, enter jointly into the idea of the Incarnation as it challenges our faith throughout the New Testament. First, it is a fact which unites itself really with the living constitution, the actual concrete and organic history, of the world as it existed previously; it was no phantasm, no spectrum, no abstract symbol only played off to the eyes of men supernaturally for the space of 33 years. Secondly, however, it is in this form a new creation; not the continuation simply of the old, but the introduction into this of a higher life (the Word made flesh), which all its powers, as they stood previously, were inadequate to reach.

Can there be any doubt, in regard to the scriptural authority of both these conceptions? They form the poles of the universal Christian consciousness as it starts in the Apostles’ Creed. They rule the whole process of theology in the Church, from the beginning, in opposition to Gnostic supernaturalism on the one hand and Ebionitic naturalism [denying the Virgin Birth and divinity of Christ] on the other. Both are presented to us from every page of the New Testament.

Christianity, shorn of either, falls at once to the ground. To make Christ an intrinsic result simply, or an extrinsic accident only, for the old creation, is to go full in the face of the whole Bible. He must be all or nothing here; the deepest and most central fact of the world, or no fact at all; the alpha and omega of humanity, or no part of humanity whatever.

By John Williamson Nevin

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #155 in 2025]

John Williamson NevinNext articles

“The power of a common life”

Nevin’s doctrine of the Eucharist in The Mystical Presence focuses on union with Christ and on the reality of the Incarnation

John Williamson Nevin“An undivided kingdom of God”

Mercerburg’s preeminent historian, Philip Schaff, fought for a united Christendom

Theodore Louis Trost