Mercersburg’s architect

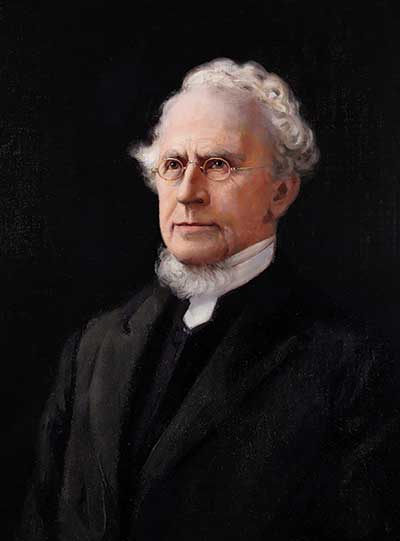

[Walter Greaves, John Williamson Nevin, 1898. Oil on Canvas, Phillips Museum of Art, #1118—Courtesy of Archives and Special Collections, Franklin and Marshall College, Lancaster, PennsylvaniA]

John Williamson Nevin (1803–1886) returned to his family farm in Herron’s Branch in 1821 near Shippensburg, Pennsylvania, broken and miserable. He had left his quiet farming community at just 14 years old—against his will, but in obedience to his father—to enter Union College in Schenectady, New York. He entered Union the youngest and smallest in his class, deeply shy and sickly. In fact Nevin’s “dyspepsia,” as it was diagnosed, was an early symptom of a lifelong anxiety about his health.

As if the stress of that was not enough, he was subjected to a coerced conversion experience that left him physically and emotionally scarred and in doubt of his faith. Young men at Union, most of whom had been raised and confirmed in the faith, were told they were hopeless sinners in need of conversion—a conversion expected to be visible and dramatic. The pressure was so great that most of them fell in with the practice. (Later, Nevin would write critically of these high-pressure conversion tactics, known as New Measures revivalism—especially as practiced by Charles Finney. See pp. 26–29.)

It was after this affair that the young Nevin came home, depressed, lacking direction, and with no hope for the future. But once again his father prevailed over him, and so he agreed to study at Princeton Seminary.

“MOST DANGEROUS MAN”

Unlike Union, Princeton provided a genuine sanctuary from Nevin’s miserable physical and emotional state. During that period he had a life-changing experience. His roommate, Matthew Fuller, advised Nevin not to drop the Hebrew course as he intended. “God might have a purpose for it,” Fuller said. Not only did Nevin persevere, he excelled and became the best Hebrew scholar at Princeton, even better than his teacher, Charles Hodge. When Hodge left Princeton temporarily for further language study in Europe, Nevin took over his class in Hebrew. This encouraged him to pursue teaching as a career.

In 1830 Nevin became professor of biblical literature at the Presbyterian Western Theological Seminary near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. During his time there, he edited a small literary and morals weekly called The Friend (meaning friend of the American antislavery movement), and he immediately was branded an antislavery crusader. His journal brought angry denouncements from Pittsburgh’s wealthy slave owners, and a prominent physician described him as “the most dangerous man in Pittsburgh.”

At Western Seminary he was required to teach church history, prompting him to study the German scholarship on the subject. Soon he mastered the German language, and through his study, became captivated by the more orthodox mediating school of German teachers. The mediators wrote in reaction to the extreme rationalism of many prominent German scholars, seeking to mediate or navigate a safe course between modern science and Christian faith.

In 1840 he was called to lead the German Reformed Seminary in Mercersburg, where he met the headmaster of the denomination’s college, Frederick Augustus Rauch, recently emigrated from Germany. Rauch left a deep philosophical impression on Nevin and contributed to his change of thought from Scottish common sense realism and Puritan tendencies to his German idealism and high-church sympathy. Influenced by German sources including August Neander, Nevin began to emphasize Christology and with it the central doctrine of the Incarnation over the more common Reformed emphasis on the Atonement. At the same time, the Oxford Movement (a nineteenth-century Anglican retrieval of Catholic ideas) influenced Nevin’s high view of the church with emphasis on ceremony, vestments, and sacraments.

MAKING WAVES AT MERCERSBURG

Soon after their meeting, Rauch died and Nevin took over leadership of both the seminary and the college. He was then joined by Swiss German scholar Philip Schaff, who would go on to become one of America’s preeminent church historians (see pp. 19–22). Immediately they were involved in one controversy after another, some minor but many as volatile as Nevin’s former stand against slavery. Nevin’s polemics included criticism of the hugely popular New Measures revivalism (see p. 30), as well as his insistence on the real spiritual presence of Christ in the Eucharist as taught by Calvin and published in Nevin’s masterpiece, The Mystical Presence (1846).

Nevin viewed the church as a divine institution given by Christ to the world for its salvation as he believed it was described in the Apostles’ Creed. This alleged “softness on Rome” led to the Classis of Philadelphia (a group of local churches within the German Reformed Church) to accuse both Nevin and Schaff of teaching doctrines foreign and harmful. Clergy gathered at the synod of 1845 overwhelmingly exonerated the professors, and Mercersburg theology continued to be taught at the seminary.

The Mystical Presence, written in the aftermath of the synod debate, clarified remaining confusion over Nevin’s views, vindicated his and Schaff’s position, articulated both Calvin’s and the later Reformed Church’s historical theology of the Lord’s Supper, and promoted the cause of evangelical catholicism (see “How to speak ‘Mercersburg,’” inside front cover).

As Nevin’s most important work, it received international recognition and lifted Nevin to prominence as one of the foremost theologians in America. But it was also the book that finally turned Hodge and Princeton Seminary against Mercersburg (see p. 12). In collaboration with Schaff, Nevin would go on to produce controversial material on the early church where he commended a great deal of Roman Catholic history and practice. Broadening his ecumenical interests, he sought to discover the “genius” of both the ancient church and the church of the Reformation. His research nearly led him to convert to Roman Catholicism, but in the end, he decided he could find fault with both systems, and he remained in the German Reformed Church.

Nevin remained at Mercersburg Seminary, but in 1841 also became president of Marshall College (later Franklin and Marshall College). While juggling his responsibilities, he published the academic journal The Mercersburg Review to bring his views to a wider audience. The Mercersburg Review began publication in 1849 as a way of publicizing the scholarship of Nevin, Schaff, and their students.

During this period Nevin utilized Schaff’s idea (derived from philosopher Friedrich Schelling) of a “Church of St. John,” which would bring together the best of the earlier Catholic “Church of St. Peter” and the Protestant “Church of St. Paul.” This journal effectively disseminated and popularized the Mercersburg theology.

While Nevin’s influence was expanding, the church question, the stress of controversy, the workload, and the precarious financial state of Marshall College all weighed heavily on him. From 1851 to 1852, he experienced what was likely a nervous breakdown, described at the time as “Nevin’s Dizziness.” Due to economic necessity, the college relocated to Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in the spring of 1853, while the seminary remained in Mercersburg. This resulted in Nevin’s first retirement, which lasted until 1861.

Having sufficiently recuperated on his farm, Nevin participated in a revision of the church’s liturgy. Naturally this prayer book reflected his high-churchmanship, and its forms radiated his evangelical catholicism. In 1857 the liturgical committee published the provisional liturgy he had helped develop (see pp. 31–33). Once again controversy surrounded Nevin. He was directly responsible for the Ordination Rite that some believed made ordination a third sacrament, something Reformed believers would not abide. The published liturgy, which was likely the most high-church leaning liturgy ever produced in America by a Reformed church, was never widely used. But the amended prayer book had lasting appeal in the denomination.

LINCOLN AND NEVIN

In 1862 Confederate troops raided the quiet farms around Mercersburg, and fierce warfare forced the closing of the seminary in 1863. Schaff took a teaching position at Andover, and Nevin gave up most of his denominational obligations. The Civil War proved to be a watershed moment in the history of America, but it had an enormous personal impact on Nevin as well. An astute student of history and politics, he often preached jeremiads criticizing much of the politics of the day and decrying what he called the “Party Spirit,” which he described as runaway pluralism. He also spoke of the Confederacy as a revolution against the legitimate government.

In practice Nevin was a Whig—one of the two main political parties at the time—however, with the rise of Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), he joined the new Republican Party (an ancestor of the current party, though with many ideological differences). Though Nevin never met Lincoln, the two probably would have been easy friends. Both hated the Jacksonian Party (Democrats, also an ancestor of and ideologically different from the Democratic Party today), especially its support of slavery. And both retained their Whig sensibilities even after the party collapsed.

They both believed in divine providence and the Romantic notion of inevitable progress toward America’s destiny as a global leader. As for the all-important issue of slavery, Nevin and Lincoln followed the same trajectory. Initially they made preservation of the Union a priority, as did most Americans. However, once victory was at hand, Lincoln would settle for nothing less than the abolition of slavery throughout America. As for Nevin, it was well known how much he desired abolition. Personally and ideologically Nevin shared much with Lincoln, including a fondness for philosophy.

WAR AND PEACE

Nevin spent most of the war despondent. Denominational strife added to his desperation. It seemed to him society was collapsing into chaos, and he often thought the central government was inept and incapable of restoring order. He initially thought the South should go its own way. But when his sons, William and Robert, joined the Union Army, he stood firmly with Lincoln on both the Union and slavery questions.

From 1862 to 1866, Nevin lectured at Franklin and Marshall College primarily in the department of history, but he was in demand as a lecturer in a variety of fields. Three years later the chapel of Franklin and Marshall College was opened and Nevin became its pastor. Former president James Buchanan (1791–1868) was frequently in attendance, and Nevin became a spiritual mentor to him.

Buchanan lived close by at Wheatland, and so he gave serious consideration to joining the chapel that had become a church. In the end he decided to join the Presbyterian Church where he had made his profession of faith. When Buchanan died in 1868, Nevin gave the eulogy.

At that time the college once again experienced financial difficulty, and Nevin was called upon to be its provisional president. The war had drastically depleted enrollment. For a short time, the college did well, but soon it was again steeped in financial trouble. Ultimately Nevin resigned in frustration in 1876.

Toward the end of his life, Nevin pursued what had always been an interest of his, mysticism, by way of the controversial Swedish mystic, Emanuel Swedenborg (1668–1772). In 1876 he wrote several articles for the Reformed Church Review having to do with “deep issues of spirituality.” They cannot be said to be mystical per se, but rather reflect Nevin’s interest in the subject in his declining years and the influence Swedenborg had on him. Although he continued to write for the Review from time to time, in 1883 his failing eyesight ended his brilliant contributions to American religious studies. Three years later, in 1886, John Williamson Nevin died, finally finding peace after a life of precarious health and bitter controversy. CH

By Linden J. DeBie

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #155 in 2025]

Linden J. DeBie is a philosopher, historian, and author of John Williamson Nevin: Evangelical Catholic and Speculative Theology and Common-Sense Religion. He edited Nevin’s The Mystical Presence and Nevin’s debate with Charles Hodge in Coena Mystica.Next articles

“The power of a common life”

Nevin’s doctrine of the Eucharist in The Mystical Presence focuses on union with Christ and on the reality of the Incarnation

John Williamson Nevin“An undivided kingdom of God”

Mercerburg’s preeminent historian, Philip Schaff, fought for a united Christendom

Theodore Louis TrostChristian History timeline: the Mercersburg movement

Chronology of Mercersburg theological movement

Anne T. Thayer