“The power of a common life”

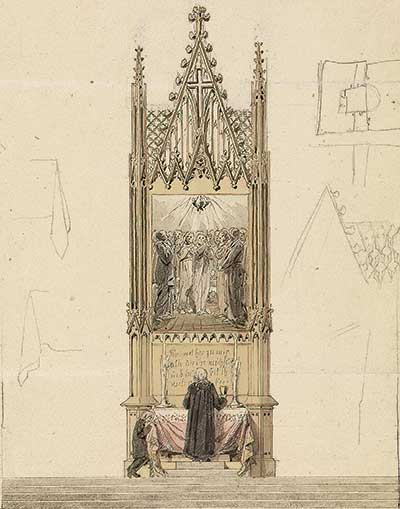

[Caspar David Friedrich, In Front of an Altar, 1817 or 1818. Drawing—Photo: Ivarsøy, Dag Andre / [CC BY 4.0] Nasjonalmuseet, Oslo]

The question of the Eucharist is one of the most important belonging to the history of religion. It may be regarded indeed as in some sense central to the whole Christian system. For Christianity is grounded in the living union of the believer with the person of Christ; and this great fact is emphatically concentrated in the mystery of the Lord’s Supper; which has always been clothed on this very account, to the consciousness of the Church, with a character of sanctity and solemnity, surpassing that of any other Christian institution.

The sacramental controversy of the sixteenth century then was no mere war of words. . . . It belonged to the inmost sanctuary of theology and was intertwined particularly with all the arteries of the Christian life.

This was felt by the spiritual heroes of the Reformation. They had no right to overlook the question which was here thrown in their way, or to treat it as a question of small importance, whose claims might safely be postponed in favor of other interests, that might appear to be brought into jeopardy by its agitation. That this should seem so easy to much of our modern Protestantism, serves only to show, what is shown also by many other facts, that much of our modern Protestantism has fallen away sadly from the theological earnestness and depth of the period to which we now refer. . . .

Any theory of the Eucharist will be found to accord closely with the view that is taken, at the same time of the nature of the union generally between Christ and his people. Whatever the life of the believer may be as a whole in this relation, it must determine the form of his communion with the Savior in the sacrament of the Supper, as the central representation of its significance and power. Thus the sacramental doctrine of the primitive Reformed Church stands inseparably connected with the idea of an inward living union between believers and Christ, in virtue of which they are incorporated into his very nature and made to subsist with him by the power of a common life.—Chapter 1

COMMUNION: THE INMOST SANCTUARY

A strong presumption is furnished against the modern Puritan doctrine, as compared with the [sixteenth-century] Calvinistic or Reformed, in the fact that the first may be said to be of yesterday only in the history of the Church, while the last, so far as the difference in question is concerned, has been the faith of nearly the whole Christian world from the beginning. It included indeed a protest against the errors with which the truth had been overlaid in the church of Rome. It rejected transubstantiation and the sacrifice of the mass; and refused to go with Luther in his dogma of a local presence. But in all this it formed no rupture with the original doctrine of the Church. . . .

The voice of antiquity is all on the side of the sixteenth century, in its high view of the sacrament. To the low view which has since come to prevail, it lends no support whatever.—Chapter 2

A CENTRAL ORDINANCE

The union of the divine and human in [the Church’s] constitution, must be inward and real, a continuous revelation of God in the flesh, exalting this last continuously into the sphere of the Spirit. Let all this be properly apprehended and felt, and it cannot fail at once to exert a powerful influence over our judgment with regard to the Lord’s Supper. For it is plain, that this ordinance holds a central place in the general system of Christian worship.

The solemn circumstances under which it was originally instituted, the light in which it has always been regarded in the Church, and the very instinct, we may say, of our religious nature itself, which no rationalism can effectually suppress, all conspire to show, that it forms in truth the inmost sanctuary of religion, and the most direct and close approach we are ever called to make into the divine presence. The mystery of Christianity is here concentrated into a single visible transaction, by which it is made as it were transparent to the senses, and caused to pass before us in immediate living representation. . . .

Low views of the sacrament betray invariably a low view of the mystery of the Incarnation itself, and a low view of the Church also, as that new and higher order of life, in which the power of this mystery continues to reveal itself through all ages.—Chapter 4

By John Williamson Nevin

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #155 in 2025]

John Williamson NevinNext articles

“An undivided kingdom of God”

Mercerburg’s preeminent historian, Philip Schaff, fought for a united Christendom

Theodore Louis TrostChristian History timeline: the Mercersburg movement

Chronology of Mercersburg theological movement

Anne T. Thayer