Pursuit of “the common and the constant”

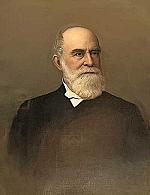

[Portrait of John Williamson Nevin in The Reformed Church in Pennsylvania by Dubbs and Hinke, 1902—Princeton Theological Seminary Library / Public domain, Internet Archive]

Perhaps no movement has shaped the piety, practice, and theology of American Protestant Christianity more than revivalism. As revivals swept the nation, thousands heard and received the gospel; hundreds were inspired to take the gospel westward across the country and eastward across the Atlantic. And yet amid revivalistic triumphs, excesses and failures alarmed the movement’s detractors. In this context heated controversy over revivalism and its effect on German Reformed churches in Pennsylvania emerged and, in response, so did the Mercersburg theology. But why exactly did Mercersburg theologians such as John W. Nevin come to loggerheads with revivalism?

FROM “NEW BIRTH” TO “NEW MEASURES”

American revivalism’s distant roots lie in the Puritan concern for heart religion and true conversion. Upon their arrival in New England, Puritans began to require a convincing “relation” or narrative of one’s conversion as a condition for church membership. Composing such relations involved considerable introspection, and they reflected an understanding of conversion found in the writings of English Puritans such as William Perkins (1558–1602), who had identified 10 stages of true conversion. These Puritans were Calvinists—they regarded this process as the work of a sovereign God who chooses some for salvation. But this Puritan understanding of the conversion process often took considerable time to play out in a person’s life, and the need to discern and chronicle it often fostered an introspective piety.

The First Great Awakening in the 1740s marked a new stage in the development of American revivalism (see CH #151). The most prominent figure here was the “Grand Itinerant”—the evangelical Anglican George Whitefield (1714–1770), whose preaching attracted large crowds throughout the colonies. A new style of preaching emerged, involving dramatic sermons designed to elicit conversion. Listeners were exhorted to experience the “new birth” then and there, rather than wait for the Puritan process of conversion to unfold. Whitefield also embodied the job description for a new and lasting figure in American religion—the itinerant or traveling evangelist.

Like their Puritan forebears, Whitefield and ministerial colleagues such as Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758) and Gilbert Tennant (1703–1764) were Calvinists who affirmed the sovereignty of God in salvation. But the Puritan emphasis on introspective subjectivity was, if anything, heightened. Whitefield, for example, insisted that the “new birth” was an intense experience that one could not fail to recognize. These two emphases—a stress on divine sovereignty and an increasing focus on human experience and agency—would eventually come to stand in tension.

The Second Great Awakening cemented revivalism as a dominant stream in American religion. Revivals sprang up in upstate New York during the 1820s and 1830s with Charles Grandison Finney (1792–1875) driving the action. Finney, as part of a broader trend during this period, moved away from Calvinism and toward an emphasis on human freedom and agency. Americans increasingly began to believe that human beings are sovereign in politics and in religion. Consistent with this, Finney contended that nothing is miraculous about a revival of religion; it is the result of applied techniques appropriate to the task. In his Lectures on Revivals of Religion, Finney wrote: “It is not a miracle, or dependent on a miracle, in any sense. It is a purely philosophical [i.e., natural] result of the right use of the constituted means.”

And so Finney utilized methods, or “New Measures,” designed to elicit conversions: direct and accessible preaching, public calls to repentance, evocative public prayers by women, house-to-house canvassing, and, most famously, the “anxious bench”—a bench or row of pews at the front of the church to which the unconverted were urged to come and contemplate their need for salvation. Through New Measures, Finney succeeded in converting thousands.

Itinerant Methodist ministers had long preached in similar fashion, and a host of imitators of Finney traversed the region of upstate New York. This area came to be known as the “burned-over district” because of how revivals swept through, leaving the populace emotionally exhausted, the area spiritually barren, and the people susceptible to a variety of unconventional religious movements.

Theology was also being retooled to fit these revivalist practices; human agency and ability were emphasized, and traditional Calvinist notions of total depravity and helplessness in the face of sin were downplayed. Key here was Nathaniel William Taylor (1786–1858), who taught at Yale from 1822 to 1857.

In his 1828 sermon “Concio ad Clerum,” Taylor contended that depravity does not consist in a sinful human nature inherited from Adam, or in any disposition or tendency to sin. Rather human sinfulness consists simply of the act of sinning and depravity in the fact that “such is their nature, that they will sin and only sin in all appropriate circumstances of their being.” In other words sin cannot be explained by any antecedent cause; while all human beings do sin, they have the power to do otherwise. Thus Taylor softened traditional Reformed teachings on human depravity and laid a foundation for revivalist techniques that assumed a more optimistic anthropology. Revivals were increasingly seen, not as a sovereign work of the Spirit of God which “bloweth where it listeth,” but as the scheduled work of preachers who encouraged people to repentance and faith.

“IRREVERENT QUACKERY”

When Nevin arrived in Mercersburg in 1840, methodological revivalism was making inroads in the German Reformed and Lutheran churches of Pennsylvania. A visiting minister attempted to implement Finney’s methods at the German Reformed church in Mercersburg, which Nevin opposed. In 1843 the first edition of The Anxious Bench was published, followed quickly by an expanded second edition in 1844. This work was simultaneously an analysis of the psychology of revivals, a critique of the theology informing revivalism, and the first extended presentation of the Mercersburg theology.

Nevin indicates at the outset that his concern is not so much the anxious bench itself; rather that the bench symbolizes a system of religion coming to expression in New Measures revivalism. The anxious bench, he continues, is a novelty and incompatible with the historic practices of the church. He rejects pragmatic arguments from the apparent efficacy of revival techniques, insisting instead that the anxious bench is a form of “quackery” that substitutes transient psychological manipulation for lasting spiritual power. As Nevin describes this revivalist perspective, “Conversion is everything, sanctification nothing. Religion is not regarded as the life of God in the soul that must be cultivated in order that it may grow, but rather as a transient excitement to be renewed from time to time by suitable stimulants presented to the imagination.”

In Nevin’s polemic we sense a bit of cultural elitism at work—he clearly regarded Finney’s revivals as tacky and unrefined. “As the spirit of the anxious bench tends to disorder, so it connects itself also naturally and readily with a certain vulgarism of feeling in religion that is always injurious to the worship of God, and often shows itself absolutely irreverent and profane.” And echoing a common theme in the antirevivalist literature of the day, Nevin viewed the expanded role of women in revivalist circles as further evidence of “grossness and coarseness in religion.”

“A WASTING FIRE”

More substantial is Nevin’s psychological and theological analysis of revivalism. The bench, he argues, poses a false issue for the conscience in that it substitutes the outward act of going forward to the anxious bench for an actual encounter with God, and it creates distractions in the minds of those who are genuinely concerned about their spiritual state.

Nevin references that portion of upstate New York where the efforts of Finney and others had been concentrated. Methodological revivalism, with its enervating focus on emotional subjectivity, had “passed as a wasting fire” through the area. Ironically this region spawned a variety of new religious sects such as the Mormons and the Oneida perfectionists, which, for all their differences, viewed religion as a matter of behavior rather than emotional experience.

Most important for Nevin, the anxious bench is a “heresy.” The problem here is an overestimation of human ability and an underestimation of the problem of sin: “Finneyism is only Taylorism reduced to practice, the speculative heresy of New-Haven actualized in common life. A low, shallow, pelagianizing theory of religion runs through it from beginning to end.” Pelagius, we will recall, was the early fifth-century theologian who emphasized free will and held that “original sin” is nothing more than bad examples that we choose to follow.

In the final chapter, Nevin presents his comprehensive alternative to the “system of the anxious bench”—what he terms the “system of the catechism.” Just as the anxious bench is a symbol for the larger system of revivalism that viewed conversion as the key moment in the Christian life, so also the catechism symbolizes the system of Christian nurture involving catechetical instruction, pastoral care, and the ministry of the word and sacrament—in short, the traditional means of grace found in the bosom of the church. Here Nevin contrasts what are, in his understanding, two distinct models of Christian piety—one focused on self-generated isolated experience, the other on a process of churchly nurture assisted by divine grace throughout life.

According to Nevin the deeper problem with New Measures revivalism is that it assumes an abstract individualism in which the convert is seen as a willing agent apart from the concrete situation in which he or she exists. For example the problem of sin is not simply in the act of sinning (as Taylor maintained). Rather it is a sinful condition, an organic disease, that all human beings share with Adam. Thus the general (the human condition in which all share) precedes and shapes the individual. Nevin goes on to argue that the “generic life,” the organic state of being “in Adam,” must be countered by a union with Christ that is just as deep and organic:

[Human] nature is restorable, but it can never restore itself. The restoration to be real, must begin beyond the individual. In this case as in the other the general must go before the particular, and support it as its proper ground. Thus humanity fallen in Adam, is made to undergo a resurrection in Christ, and so restored flows over organically as in the other case to all in whom its life appears. The sinner is saved then by an inward living union with Christ as real as the bond by which he has been joined in the first instance to Adam.

Here Nevin reveals the focus of Mercersburg theology: the person of Christ. This Christ-centeredness implies, moreover, the centrality of the church as the body of Christ. The source of this saving restoration, Christ himself, is to be found in the life and ministry of the church. Once again the general precedes the individual. The church is not to be thought of as merely the aggregate of individual Christians, as a “sandheap” as Nevin often terms it:

Due regard is had to the idea of the Church as something more than a bare abstraction, the conception of an aggregate of parts mechanically brought together. It is apprehended rather as an organic life springing perpetually from the same ground, and identical with itself at every point. In this view the Church is truly the mother of all her children. They do not impart life to her, but she imparts life to them.

For Nevin, this churchly sensibility has substantial practical implications. Children are baptized into the church with the expectation that they will grow into faith as they are nurtured by the means of grace, and this without need for the “sudden and violent” emotions of the revival service:

[I]t is counted not only possible, but altogether natural that children growing up in the bosom of the Church under the faithful application of the means of grace should be quickened into spiritual life in a comparatively quiet way . . . without being able at all to trace the process by which the glorious change has been effected.

Of course family life, and the spiritual nurture it provides, is fundamental to this view of the church.

CATECHISM IN ACTION

The pastoral ministry of the word and sacrament are central to this “system of the Catechism” that Mercersburg preached and practiced. This, for Nevin, includes not only the stated weekly church services, but also household visitation by ministers. Nevin concedes that this ongoing pastoral care may be less exciting than the sound and fury of the anxious bench, but he avers that “the common and the constant are of vastly more account than the special and transient.”

In Nevin’s exposition of the “system of the Catechism,” we see important themes that would be central to the Mercersburg theology as it developed—organic union with Christ, the generic humanity of Adam and Christ that determine the identity of those joined with them, the mediation of the church, the priority of the general over the particular, and the corporate church over the individual Christian. CH

By William B. Evans

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #155 in 2025]

William B. Evans is the author of A Companion to the Mercersburg Theology: Evangelical Catholicism in the Mid-Nineteenth Century, from which this article is adapted.Next articles

Revival, rightly understood?

John Williamson Nevin and “New Measures” revivalism

John Williamson NevinMercersburg’s “worship war”

Crafting a new liturgy for the German Reformed Church created conflict, but also a lasting legacy

Walter L. TaylorMystic, sweet Communion

Excerpts from the liturgy for Holy Communion from the provisional Mercersburg liturgy of 1857

German Reformed Church in the United States of AmericaCentering Jesus

Emanuel Vogel Gerhart, a student of Mercersburg, became one of its key advancers

Annette G. Aubert