Mercersburg’s “worship war”

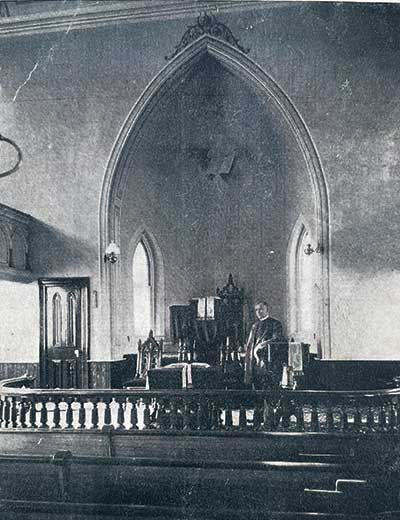

[Postcard of Chancel of Christ Reformed Church, Indian Creek, Pennsylvania, 1905—Photo by Melody Belk / Christian History Institute Archives]

Any attempt to change a church’s worship is fraught with conflict. In recent decades many books have been written about the “worship wars” in American Protestantism. But conflicts over worship are nothing new. One might even read the Bible itself as a narrative about one worship war after another, from Genesis to Revelation: arguments over whom God’s people are to worship, how they are to worship, and even where they are to worship. The history of the people of God is, among other things, the history of worship wars.

One such worship war broke out in the German Reformed Church in the mid to late nineteenth century when the denomination embarked on a process of revising its liturgy. By any measure its results were mixed, with some in the German Reformed Church embracing these revisions and others denouncing them. Yet the liturgical manual they produced has had far-reaching significance for Reformed churches around the world.

A LITURGY LOST. . .

When the German Reformed Church first began to establish congregations in America in the early 1700s, they lacked many resources. While they had a liturgical tradition going back to the Reformation, shaped by the Reformed liturgy from the German Palatinate (centered in Heidelberg), this liturgy was largely unavailable for these colonial congregations. It became a distant memory by the middle of the nineteenth century. The worship of the German Reformed Church varied from one congregation to another, as was the case in other American Reformed denominations.

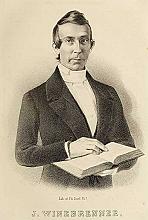

In 1849 the Synod of the German Reformed Church (its national assembly) appointed a committee to produce a revised liturgy for the denomination. Philip Schaff served as the committee’s chair, and John Nevin was a member of the committee as well. As the two figures at the center of the Mercersburg movement, they had significant influence on the shape of the liturgy the committee proposed. The worship manual they produced was a liturgical expression of Mercersburg theology. The first edition of the liturgy was published late in 1857 under the title The Liturgy or Order of Christian Worship, though it was known better as the “provisional liturgy,” given its interim nature. The final revised liturgy, published with the title Order of Worship for the Reformed Church in the United States, came out in 1866.

While some in the German Reformed Church wished simply to resurrect the liturgy of the Palatinate and go no further back than the Reformation, the committee sought to produce a liturgy that drew on the history of the Christian church from its earliest days to the present. At the same time, the committee realized that any form of worship they included had to be relatable to those who were expected to use it. To this end the committee drew from the worship life of the ancient, medieval, and Reformation periods, looking for what would be useful to a denomination planted in the United States.

In addition the work of the committee reflected the reading of church history shared by Schaff and Nevin. While they both agreed that the Reformation remained a profoundly important period, they thought that even the Reformation was but one part of the larger history of the church that should not be broken off from what preceded it. For Mercersburg theology the Reformation was a reform movement within the holy catholic church, and not simply a rejection of all that had come before.

. . . A LITURGY REIMAGINED

This approach led the committee to produce a liturgically rich form of worship. Its critics, however, saw in this liturgy a rejection of certain Reformed doctrines. For example, the Communion “table” was referred to as an “altar,” which drew the ire of some. The Communion prayer used language some saw as too similar to a Roman Catholic notion of eucharistic sacrifice. Many of the same critics judged that the ordination service introduced a doctrine of ministry that was too priestly and out of keeping with the traditional doctrine and practice of the Reformed tradition. Even the fact that the proposed liturgy provided set responses for the worshipers became an object of criticism.

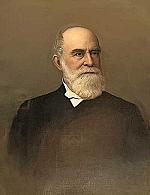

All of this led to a series of articles, monographs, letters, and debates on the floor of the synod and the classes (regional bodies of the denomination). Some parts of the denomination accepted the Order of Worship, but others rejected it. John H. A. Bomberger (1817–1890), who served on the committee, eventually became its fiercest critic (see pp. 38–41). He argued that the committee’s finished product was an attempt to impose “ritualism” on the German Reformed Church. But Nevin himself was among the most avid and able defenders of the new liturgy.

Broadly speaking the eastern portion of the German Reformed Church, which was in closer proximity to Mercersburg (and Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where the seminary later relocated in 1871), supported and appreciated the liturgy. Much of the opposition was among congregations and ministers in the western portion of the denomination (in states like Ohio) and in the South (particularly in North Carolina). By 1881 the synod of the denomination appointed a “Peace Commission” to work toward reconciliation in the denomination because of the conflict produced by the liturgical controversy.

(RE)ORDERING WORSHIP

In the end diversity of practice continued to characterize the liturgical life of the German Reformed Church (later simply the Reformed Church in the United States, or RCUS). But even the liturgies created by critics of the Order of Worship used much of what was in it, though they removed the portions they found objectionable. The RCUS came out of the liturgical controversy with a deeper sense of the meaning of its worship. So while not a complete success by any measure, the Order of Worship had a long-lasting impact on the life of the denomination.

One may find, still today, congregations with an architecture inspired by Mercersburg theology and the liturgy of the Order of Worship among old German Reformed Churches now within the United Church of Christ (UCC). These church buildings have a “divided chancel” (with a lectern and pulpit on either side of the chancel) with the Communion table at the center, with altarlike woodwork on the wall behind the table.

But perhaps the most significant and longest lasting influence of the Order of Worship was its international, ecumenical impact. In the latter part of the nineteenth century, many Reformed denominations in the English-speaking world (including North America and Great Britain) began to reassess the worship life that they had inherited. While many Reformed Protestants simply assumed that their worship was a continuation of the practices of the Reformation, more scholars and pastors became acquainted with the older liturgies of the Reformation and saw a difference.

They discovered that the worship they had inherited (“the worship of our fathers,” as they would say) was largely shaped by a kind of antiliturgical Puritanism. This led to something of a liturgical “recovery” movement on both sides of the Atlantic among Reformed Protestants.

Elements that had disappeared from Reformed worship under the censure of Puritanism (like the regular use of the Ten Commandments, the Lord’s Prayer, the Apostles’ Creed, the Doxology, etc.) had been present in the liturgies of the Reformers. Thus the latter half of the nineteenth century became a time of liturgical study, discovery, recovery, and adaptation for Reformed denominations. Interested pastors began to produce unofficial books of worship, and denominations later followed with official versions.

The German Reformed Church, in many ways, led this movement. In fact the liturgies appearing in the Order of Worship became resources for both American and Scottish Reformed denominations as they produced their own Book of Common Worship or Book of Common Order. So while the influence cast by the work of the Liturgical Committee of Schaff, Nevin, and others may have had limited immediate impact in their own denominational world, it contributed to a rich recovery of Reformed worship internationally. It also served as a catalyst for an ecumenical interest in recovering more ancient practices of worship.

The Liturgical Committee, gathering as it did in the homes of its members or in the church buildings where they served, probably could not have imagined that the work they were doing would develop beyond just one more worship war—becoming instead an influence on liturgy and worship practices across denominational lines and around the world. CH

By Walter L. Taylor

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #155 in 2025]

Walter L. Taylor is the pastor of Oak Island Evangelical Presbyterian Church.Next articles

Mystic, sweet Communion

Excerpts from the liturgy for Holy Communion from the provisional Mercersburg liturgy of 1857

German Reformed Church in the United States of AmericaCentering Jesus

Emanuel Vogel Gerhart, a student of Mercersburg, became one of its key advancers

Annette G. AubertPerspectives on Mercersburg

A theological roundtable

Jennifer Woodruff Tait, William B. Evans, John H. Armstrong, and the editors