Centering Jesus

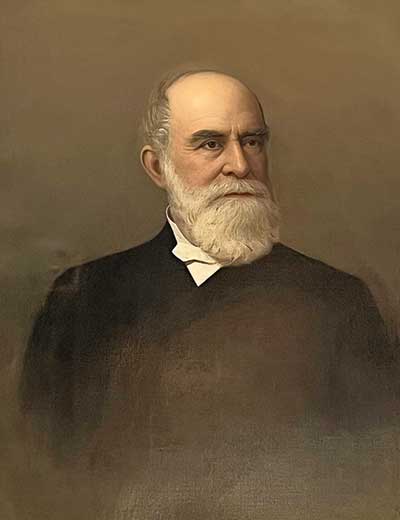

[W. A. Greaves, Reverend Emanuel Vogel Gerhart, 1894. Oil on canvas. Phillips Museum of Art Collection, #3519—Courtesy of Archives and Special Collections, Franklin and Marshall College, Lancaster, Pennsylvania]

In Mercersburg’s early days, controversy propelled its theology to public attention; the Civil War and national turmoil caused that attention to fade. Yet even after momentum waned, the movement continued, and in the present day, we see its theology as cohesive and systematic rather than as a collection of loosely related, similar ideas. What made this possible?

Mercersburg’s students, who sat under John Nevin’s and Philip Schaff’s teaching, later advanced it. Of those who went on to make distinctive contributions to the Mercersburg movement, and American religion as a whole, Emanuel Vogel Gerhart (1817–1904) is perhaps the most important.

A CHRISTOCENTRIC THEOLOGY

Gerhart was born in Freeburg, Pennsylvania, in 1817 to a family whose ancestors had immigrated to the United States from Alsace in 1730. His father, Isaac Gerhart (1788–1865), was one of the first German Reformed Church ministers in North America. His mother, Sarah Vogel Gerhart (1790–1861), was raised in a French Lutheran environment. Emanuel himself eventually raised four children with Eliza Rickenbaugh, whom he married in 1843.

After receiving a homeschool education from his father, Gerhart excelled academically at the Classical School of the German Reformed Church in York, Pennsylvania. He had the privilege of being educated by Frederick August Rauch (see pp. 38–41), another German immigrant. Rauch introduced Gerhart to many German intellectual traditions and philosophical ideas in his native language, resulting in Gerhart’s thorough knowledge of the works of German authors and of the foundational ideas underlying Romanticism and the Enlightenment.

After graduating from Marshall College in 1838, Gerhart continued his studies at Mercersburg Theological Seminary. There he first heard Nevin’s proposal that a theological system should be founded on the principle of the Incarnation. Gerhart was also introduced to German theology and the idealist philosophy of Hegel at Mercersburg.

Arguably Gerhart’s most important contribution to the Mercersburg movement was his dogmatic Christocentric work Institutes of the Christian Religion (1891, 1894), its title purposefully taken from John Calvin’s dogmatic text. Gerhart’s work on Christocentric dogmatics was the first of its kind published in America. He used this work to explain how Christology was at the center of his theology. Schaff described Gerhart’s Christocentrism and other theological insights as among the primary outcomes of the Mercersburg movement.

In addition to Institutes of the Christian Religion and a long list of journal essays, Gerhart published two influential texts: An Introduction to the Study of Philosophy with an Outline Treatise on Logic (1857) and Prolegomena to Christian Dogmatics (1891), the latter of which emphasizes Christocentric principles. For many American students, the former was their first encounter with modern philosophical ideas. The latter focuses on how the divine and human natures of Jesus Christ function as a cornerstone for Christian doctrine.

Gerhart, like his teacher Nevin, expressed great respect for early Christian creeds and the writings of the church fathers, especially Augustine. Gerhart synthesized the ideas of Augustine and Calvin with those of nineteenth-century German mediating theologians such as Isaak Dorner and Hans Lassen Martensen (1808–1884), combining the core principles of tradition and modernity to produce original ideas such as those found in Institutes.

PASTOR, PRESIDENT, PROFESSOR

Gerhart participated in all aspects of theological education, beginning as an instructor at an all-women’s seminary in Mercersburg and later as a lecturer at Marshall College. He also served as pastor at the Reformed Church of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, from 1843 to 1849, before moving to a small mission church in Cincinnati. By 1851 he was living in Tiffin, Ohio, to fulfill an appointment as president and professor of theology at Heidelberg College and Theological Seminary, an institution that addressed the growing need for Reformed Church ministers across the Midwest.

In 1855 Gerhart returned to Marshall (which had become Franklin and Marshall College in the meantime) to serve both as its first president and as professor of mental and moral philosophy. He retained his leadership position throughout the Civil War and Reconstruction. Among other accomplishments during his presidency, Gerhart collaborated with Schaff as coeditor of The Mercersburg Review. In 1868 he became professor of systematic theology and president of Mercersburg Theological Seminary.

Although Gerhart had never studied in Europe, he immersed himself in the European literature he had access to. This supported his active engagement with theologians associated with the new school of mediating theology that emerged from a group of German scholars interested in topics such as supernaturalism and rationalism, liberalism, and orthodoxy. One of the school’s primary motivations was to find a middle ground within the Protestant theological establishment. Mediating theologians viewed Christology as central to these dogmatic systems, but they also worked to create bridges connecting the Christian faith with modern science.

Initially the movement experienced a mixed reception among Reformed theologians in America. However, Gerhart used the knowledge he had accrued through reading many European texts to support an original dogmatic work describing the importance of mediating theology. His successful defense of mediation did not overlook Calvin or classical texts written by the church fathers. Indeed, they formed the foundation upon which he built mediating ideas into his theology, ideas he considered useful for addressing modern cultural challenges and for navigating tensions between religious beliefs and contemporary concerns.

GERHART AND THE PROFOUND MYSTERY

When advocating for a sacramental theology in the tradition of Mercersburg, Gerhart declared that any ecclesial body lacking the sacraments had lost its identity as a church. Rather than mere “empty forms,” he argued that the sacraments are significant “signs and seals of God’s covenant” with believers and described eucharistic and baptismal functions as vital “means of grace.” Similar to the views of his Mercersburg colleagues, his argument diverged from the Zwinglian interpretation of the Eucharist as a memorial meal—a prevalent perception among American Protestants at the time. Like Nevin, Gerhart articulated a dual understanding of the Lord’s Supper as both a commemorative rite and spiritual nourishment, focusing on its role as an act of grace sustaining the spiritual lives of believers.

Gerhart relied on Calvinist theology and Reformed confessions in his analyses of the sacraments, describing each one as a way for believers to receive spiritual blessings from Christ. Unlike the Anabaptist perception of baptism as an ordinance, Gerhart viewed it as a profound mystery offering God’s grace to believers. However, he did not believe that baptism exerts any effect on ethical human nature; instead he argued that ethical changes require repentance and faith. He emphasized that the spiritual meaning of baptism is due to the work of the Holy Spirit.

Gerhart also expressed concern about the failure of many American churches to prioritize essential church principles. In a time when both sectarianism and New Measures revivalism occupied most American denominations, Gerhart noted with dismay the absence of focus on church doctrine.

According to his Institutes, the church is best viewed as Christ’s body, an idea emphasizing its spiritual nature. He depicted the church as both a supernatural and an organic communion—an establishment of God’s kingdom composed of the elect. In his book he further described the church as a “new or second human race” originated “by spiritual birth from the glorified Christ” and supported by “the immanent presence of His Holy Spirit.”

Drawing from biblical tradition, Gerhart incorporated the New Testament’s mustard seed metaphor to describe its progressive development. Other images he used included “the mystical body of Jesus Christ” and “a living mystery” that is both “divine and human.”

Like other Reformed theologians, Gerhart was concerned about a correct presentation of the doctrine of Atonement, and he returned to this task in various texts. He approached the atonement as an organic concept encompassing Christ’s Incarnation, death, and Resurrection. Rather than treat them as isolated events, he emphasized their unity as essential components of a singular redemptive act—a view that set him apart from other American Protestants.

THE "SEED OF RELIGION"

Reflecting his interest in apologetics, Gerhart proposed an inherent inclination toward religion in humans, a view similar to Calvin’s assertion that all of humanity possesses a natural awareness of divinity, or “seed of religion.” Gerhart argued that this awareness is part of human nature rather than something acquired through study or contemplation and that the inclination toward worshiping a divine being is a universal experience that all people share.

Gerhart agreed with Nevin’s critique of the external practices of modern revivalists, warning that they might lead followers to overlook the core message of the gospel. He felt that modern revivalists gave too much weight to personal and subjective religious experiences at the expense of important teachings about Christ. He responded by underscoring the importance of sermons and education, insisting that young people apply themselves to learning the catechism as a means of countering the limitations of modern revivalism.

On April 28, 1904, Emanuel Gerhart suffered a bad fall while entering a building at Lancaster Theological Seminary. The books he was carrying eased his fall, perhaps preventing an immediately fatal head injury. After giving a lecture a few days later, his health suddenly declined, and he died on May 6. As a key leader in the German Reformed Church community, his death was a considerable loss.

Gerhart lived during a period of significant intellectual and social upheaval that positioned the church at a crossroads. His substantial contributions of systematizing and developing Mercersburg theology received serious attention during the nineteenth century, offering glimpses into the movement that anticipated Karl Barth’s neo-orthodoxy. In the April 1918 issue of Reformed Church Review, he was called Mercersburg’s “great instructive genius.” Like the mediating theologians before him, Gerhart became a mediating figure himself, emphasizing Christocentric perspectives as he tackled the challenges faced by the church during this era. CH

By Annette G. Aubert

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #155 in 2025]

Annette G. Aubert is a historian, lecturer at Westminster Theological Seminary, Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, and author of The German Roots of Nineteenth-Century American Theology and Christocentric Reformed Theology in Nineteenth Century America: Key Writings of Emanuel V. Gerhart, from which this article is adapted with permission from Wipf & Stock Publishers.Next articles

Perspectives on Mercersburg

A theological roundtable

Jennifer Woodruff Tait, William B. Evans, John H. Armstrong, and the editorsRecommended resources: Mercersburg movement

Learn more about the Mercersburg movement’s main figures, critics, influences, and legacy with these recommendations from Christian History’s authors and editors.

the authors and editorsQuestions for reflection: Mercersburg movement

Questions to help you reflect on the legacy of the Mercersburg movement

the editors