Punching up

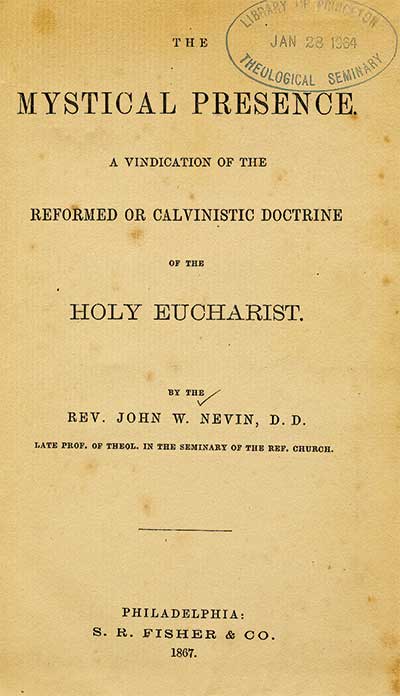

[Above: John Williamson Nevin, The Mystical Presence, 1867—Princeton Theological Seminary Library / Public domain, Open Library]

In a tiny town in south-central Pennsylvania, some 40 miles west of Gettysburg, several professors in a small theological seminary worked tirelessly in the 1840s. This seminary at Mercersburg, affiliated with the small and somewhat marginalized immigrant German Reformed Church, was far from the urban intellectual centers of the day. Nor did it have access to the financial and intellectual resources afforded to larger and better-connected schools, such as Princeton Seminary. Nevertheless it quickly earned the attention of the theological world.

Truth be told, John Williamson Nevin (1803–1886) and Philip Schaff (1819–1893) were swimming against the stream of nineteenth-century American Protestantism with its individualism, revivalism, and pragmatism. As they interacted with leading theologians of the nineteenth century, both in America and abroad, it became clear that Nevin and Schaff had no problem “punching above their weight” and were quite willing to challenge prevailing theological ideas.

In their own Reformed circles—that is, a theological tradition coming from the Protestant Reformation and often associated with John Calvin—they debated the New England Congregational Calvinists as well as the Princeton Presbyterians over their tradition’s nature and shape. They suggested a substantial alternative to New England’s evangelical moralism, as well as to Princeton’s scholasticism that foregrounded the doctrines of predestination and forensic justification. They also pointed to issues and themes ignored in the larger American church—the centrality of the Incarnation, the importance of the church as the people of God and the sphere of salvation, the sacraments as objectively real means of grace, and the importance of liturgical worship that proclaimed and mediated these objective realities to the faithful.

But as the Civil War erupted and American religion experienced dramatic shifts and changes in the postwar period, the Mercersburg movement and the theology it generated began to fade from view. Nevertheless the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries have seen a marked revival of interest in the theology of Nevin, Schaff, and their students, interest due not only to the formidable intellects of the two main protagonists—Nevin and Schaff—but also to the power and relevance of the theology they formulated. In 1955 historian Scott Francis Brenner wrote these effusive words:

The meeting of Schaff and Nevin was like the concurrence of two heavenly bodies of the first magnitude. The splendor which ensued is known as the Mercersburg Theology, for these two intellectual giants of the Presbyterian-Reformed household of faith wrought out a theological system of singular boldness, relevant to its time, distinctively ecumenical, and of unquestioned enduring worth.

Perhaps the Mercersburg theologians have something substantial and relevant to say to us today.

THE MERCERSBURG VISION

Founded in 1825 the German Reformed Seminary was located initially in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and housed in the facilities of Dickinson College. It moved to the nearby city of York in 1829, and then to the town of Mercersburg in 1837. (The seminary moved to its current location in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in 1871.) Money was tight, and at first a single theology professor, Lewis Mayer (1783–1849), taught the classes. Friedrich Augustus Rauch (1806–1841) arrived from Germany in 1832 and taught biblical literature and church history at the seminary. He was instrumental in introducing the idealism of the German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel to America. Hegel and other German thinkers, such as philosopher Friedrich Schelling and theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher, were seminal influences on the Mercersburg theology (see “How to speak ‘Mercersburg,’” inside front cover). These German modes of thought, alien to most Americans at that time, contrasted starkly with the empiricist philosophy of Scottish common sense realism that reigned in nineteenth-century America and shaped much of the theology of the period.

Rauch died suddenly in 1841 at the young age of 34, but by then, John Williamson Nevin had joined him at the seminary (see pp. 14–17). A native of southeastern Pennsylvania and a graduate of Princeton Theological Seminary, Nevin had taught biblical literature at the Presbyterian Western Theological Seminary for 10 years before being recruited by representatives of the German Reformed Synod to teach theology at Mercersburg in 1840. Already familiar with German theological scholarship upon his arrival at Mercersburg, Nevin would become, more than anyone else, the catalyst and theologian of the Mercersburg theology movement.

In 1844 Philip Schaff joined Nevin at Mercersburg. Synod representatives recruited him from Germany to teach biblical literature and church history at the seminary (see pp. 19–22). Despite their differing backgrounds—Nevin, the Scots-Irish Presbyterian, and Schaff, the product of both Continental German Reformed and Lutheran influences—the two men quickly found that they shared a remarkably similar theological perspective on the issues of the day. Both were steeped in the Christocentric theology of the German mediating theologians and in German idealism, which informed their understanding of the church and church history.

They believed that history is the dialectical unfolding of ideal principles, and that the strife, struggle, and contradictions evident in the church’s history, from its ancient origins through the modern period, would be resolved in a more perfect expression in the church of the future. Therefore, both Schaff and Nevin insisted upon the theological importance of the church’s ultimate unity throughout history—a conviction that informed the budding ecumenism of the Mercersburg movement. For this reason the chaos of competing denominations and sects they saw in nineteenth-century America deeply disturbed them.

ANTIREVIVALIST ROMANIZERS

Such ideas were strange to many, both inside and outside the German Reformed Church, and Nevin and Schaff soon found themselves involved in controversy. However, they did not shy away from debate, and Nevin in particular was a formidable polemicist. Nevin’s critique of Second Great Awakening revivalism, The Anxious Bench (first published in 1843 and again in a much expanded second edition in 1844) attacked Charles Finney’s revivalist methods and the conversionist theology that undergirded them (see p. 30).

Schaff’s inaugural lecture, published as The Principle of Protestantism, argued against the apostasy theory, or the then-popular notion that the true church devolved into catholic darkness after the death of the apostles only to be rediscovered, wonderfully, by Martin Luther in the sixteenth century. He proposed a higher appraisal of Roman Catholicism, going so far as to argue that the church of the future must bring together the best qualities of Rome and Protestantism. Not surprisingly he was almost immediately condemned by some in the German Reformed Church as a “Romanizer.”

Nevin’s The Mystical Presence was published in 1846 and argued on biblical, theological, and historical grounds for a recovery of John Calvin’s doctrine of the real presence of Christ in the Lord’s Supper (see p. 18). Such Eucharistic ideas, however, stood in considerable tension with Zwinglian memorialism—a view that Christ’s presence in Communion was a mere remembrance, or a memorial, as opposed to a real presence of Christ’s incarnate humanity—which prevailed in much of American Protestantism. Again the charges of Romanizing came from Mercersburg’s opponents both inside and outside the German Reformed Church. A clash of titans ensued in Nevin’s memorable debate (1846–1850) with Charles Hodge (1797–1878) of Princeton on this topic. Many historians believe that Nevin won by a considerable margin.

In 1849 the Mercersburg Review was founded as a venue for Nevin’s and Schaff’s literary efforts. Nevin wrote prolifically, producing almost 50 articles in the first four years of publication. His evolving theological interests were evident in these first four volumes of the Review. Early on his work focused especially on the importance of the Apostles’ Creed and on the dangers of sectarian Protestantism. Then his attention shifted to Christology and to the history of the early church as Nevin pondered the discontinuity of the Protestantism of his day with early Christianity and considered becoming Roman Catholic. The dramatic break in Nevin’s literary activity after the 1852 volume of the Mercersburg Review reflected his personal struggles.

Physically worn out by his herculean literary efforts and his teaching and administrative labors at the seminary and Marshall College, and haunted by the possibility that the Protestant experiment was irreparably flawed, he entered a period of emotional breakdown that became known as “Nevin’s Dizziness.” Nevin contributed occasionally to the Review from this point on, but students of Rauch, Nevin, and Schaff carried the Mercersburg perspective forward in the Review.

Schaff’s contributions also grew, and his fruitful research into the history of the early church continued. By this point, however, the initial burst of Mercersburg’s theological creativity had subsided. But the task of systematizing the Mercersburg theology remained, undertaken most notably by Emanuel Gerhart (see pp. 35–37). Mercersburg thinkers also focused on generating liturgical resources for the German Reformed Church that reflected their insights and ethos.

DECLINE AND DETRACTORS

Though the liturgical sensibilities of Mercersburg continued to influence many German Reformed congregations, the distinctive theological agenda of Mercersburg began to wane. Post–Civil War America, dealing with rapid urbanization and massive immigration, looked much different from the antebellum period. In Germany a neo-Kantian theology displaced Schleiermacher and Hegel. Soon this classical Protestant liberalism, which was naturalistic and moralistic, arrived in the United States and helped generate the social gospel movement.

In comparison the Mercersburg theology—with its focus on the Incarnation and the Resurrection and its ecclesial regard for the church as a supernatural organism—seemed dated. Evidence of this eclipse even within the German Reformed Church is found in a 1912 article by Lancaster Theological Seminary church historian George Warren Richards (1869–1955), who wrote that “the formulas of the Mercersburg school are no longer pertinent and adequate” and that “the Mercersburg system has ‘had its day and ceased to be.’” The continuing significance of the movement, he suggested, lay in how Nevin and Schaff “paved the way for a transition from Puritanism to Modernism.”

After the First World War, the dialectical theology of Karl Barth (1886–1968) and others emerged. Whereas Mercersburg had embraced historical consciousness and scholarship, Barth sought to flee from the acids of historical criticism by locating the historical foundation of Christianity in the realm of “suprahistory,” where it could not be proven or disproven by historical inquiry. Doubtless Mercersburg’s regard for Schleiermacher, whom Barth criticized, was an embarrassment as well. Finally Mercersburg’s high ecclesiology and view of the church as the sphere of salvation did not mesh well with Barth’s low-church, Zwinglian sensibilities.

“SPARK OF PROPHECY”

But even during the heyday of the dialectical theology, the stage was being set for revived interest in Mercersburg. By the early twentieth century, the ecumenical movement was spreading in the United States and in Europe. The great 1937 ecumenical meetings at Oxford and Edinburgh expressed sentiments regarding church unity similar to the conclusions of Nevin and Schaff. Church historian George Warren Richards, who ironically had dismissed the significance of Mercersburg theology four decades earlier, noted now: “Schaff and Nevin were far-sighted men who had at least a spark of prophecy in their theology.”

Around the same time, a liturgical renewal movement within Roman Catholicism was spilling over into Protestant denominations, sparking interest across denominational lines in the recovery of ancient church practices. Just as Nevin and Schaff had done a century earlier, liturgical-renewal scholars drew heavily on the worship traditions of the early church.

Soon articles and books appeared, praising Nevin and Schaff as theologians of enduring significance and suggesting that the Mercersburg thinkers had something to offer the contemporary church after all. Particularly significant were lectures presented at Austin Presbyterian Theological Seminary in 1960 by University of Chicago’s church historian James Hastings Nichols (1915–1991). These lectures were published in 1961 as Romanticism in American Theology: Nevin and Schaff at Mercersburg. Nichols’s volume provided the first extended scholarly analysis of the Mercersburg theology. He said that Nevin and Schaff were “major prophets of the twentieth-century ecumenical movement,” adding that “they ranked easily among the first half dozen American theologians of their generation.”

But many of the Mercersburg writings were long out of print or found only in the musty pages of the Mercersburg Review. Text accessibility was a real problem, and so in the mid-1960s the reprinting of significant Mercersburg writings began. Schaff’s The Principle of Protestantism and a collection of Nevin’s The Mystical Presence and Other Writings on the Eucharist appeared in the never-completed Lancaster Series on the Mercersburg theology in 1964 and 1966 respectively.

Anthologies that collected key Mercersburg texts on important doctrines—the church, Christology, the sacraments, ministry, and human freedom—as well as Nevin’s and Schaff’s significant writings, were published and began circulating in the 1960s and 1970s. The task of republishing Mercersburg texts continues today in the Mercersburg Theology Study Series.

MORE THAN A REFORMED REFRESHER?

While initially concerned with problems facing the German Reformed Church in America and the character of the Reformed tradition, the Mercersburg theology also spoke to issues relevant to American evangelicalism and to mainline Protestants. Both Nevin and Schaff, though recognizing the Christian’s vital experience of salvation, harshly critiqued the revivalist excesses, rampant subjectivity, low sacramentology, historical amnesia, and lack of liturgical sensibility that they thought characterized American Protestant evangelicalism. More than a few evangelicals have found these traits that Nevin and Schaff considered so troubling present in the church today and have turned to Mercersburg for an antidote.

Thus, the contemporary revival of interest in the Mercersburg theology has brought together a remarkably broad spectrum of Christians—from members of liberal mainline denominations interested in ecumenism and liturgical renewal to evangelicals seeking a deeper and more historically informed experience of the Christian faith. Reflecting on the formation of a society devoted to the discussion and preservation of Mercersburg distinctives, liturgical scholar Howard Hageman (1921–1992) wrote in 1985:

The larger majority of those present were working pastors (and some laypeople) who are uneasy about the integrity of the Reformed tradition in today’s America. Repelled by the sterility of a fossilized Calvinism, appalled by the success of a mindless evangelicalism, and discouraged by the emptiness of classic liberalism, they are looking for a fresh understanding of the Reformed tradition. Mercersburg, with its emphasis on incarnation, church, sacraments, and ministry as essential elements of that tradition, seems to offer at least an interesting possibility.

Could it be that Mercersburg’s “evangelical catholicism” is as provocative and intriguing today as it was in the time of Nevin and Schaff? CH

By William B. Evans

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #155 in 2025]

William B. Evans is the Eunice Witherspoon Bell Younts and Willie Camp Younts Professor of Bible and Religion Emeritus at Erskine College. This article is adapted from A Companion to the Mercersburg Theology: Evangelical Catholicism in the Mid-Nineteenth Century.Next articles

“The power of a common life”

Nevin’s doctrine of the Eucharist in The Mystical Presence focuses on union with Christ and on the reality of the Incarnation

John Williamson Nevin