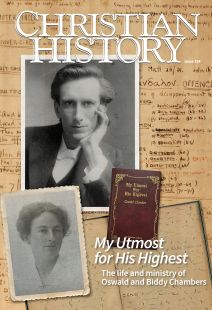

From typewriter girl to publishing powerhouse

[Above: Woman Typist, c. 1900—Public domain, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division]

Widowed, in the foreign field, mother of a toddler, and administrator of an international ministry, Biddy Chambers stared down a mountain of unopened mail and wondered how to carry on after the death of her husband, the charismatic preacher Oswald (see pp. 18-20). Would she stay at the Zeitoun YMCA camp? Would she return to England as a pensionless widow to eke out a living in a secretarial pool? What would happen to the international ministry she had built with her husband during their seven years of marriage? As she sorted through letters on the morning of January 7, 1918—barely two months after burying Oswald in a Cairo cemetery—“the way opened.”

The director of the Nile Mission Press wrote that “he was printing The Place of Help in Arabic for their magazine, and also that he wanted a psychology book to study for his talks.” The Place of Help was originally printed in the newsletter of the Chamberses’ ministry in England. Now printed in Arabic, missionary publishers wanted more of Oswald’s words to help their work across northern Africa and beyond.

This request marked a significant turning point in Biddy Chambers’s life and career (see pp. 24–26). But what enabled this former secretary to become an unprecedented publishing phenomenon?

THE WHITE BLOUSE REVOLUTION

Women’s work was changing in turn-of-the-century England. Chambers was one of over 60,000 women called “white blouses” who revolutionized the workplace. From 1850 to 1914, the number of clerks in Britain increased from 95,000 to 843,000. Women accounted for nearly 20 percent of the swelling ranks, their ranks growing from 2,000 to 166,000 by the start of World War I.

This growth also coincided with a technological innovation: the typewriter. A corresponding workplace innovation—the female typist—was dramatized in Grant Allen’s The Typewriter Girl. Published in 1897, this novel depicts the journey of a lower-middle-class woman who was trained as a secretary and typist before filling a central role in the growing British economy.

Chambers, then Gertrude Hobbs, took a clerical position at the Woolwich Royal Arsenal the same year The Typewriter Girl was published. A correspondence stenography course from Pitman Metropolitan School made her excellent at shorthand, but it was her additional skill as a typist that set her apart. As The Typewriter Girl dramatizes, “every girl in London can write shorthand.” Women like Hobbs who were trained stenographers and typists were in high demand, and their multipurpose skills were compensated accordingly. In industrial centers like Manchester, female stenographers and typists could earn up to double the wages of other secretaries. Even then their earnings were still significantly lower than men’s.

Work for middle-class women was assumed to be a temporary situation, either to add supplementary income to a male-headed household or as an economic stopgap before marriage. “Marriage bans” against married women working reinforced the assumption that working women were single women. Ironically women entered the workforce in part to make up for the lagging population of working-age—and marriageable—men.

At the start of her career, Hobbs had no serious prospects of marriage and likely considered her career as a long-term plan for financial stability. Her friend and fellow secretary Marian Moore had similarly ambiguous marriage prospects. Their shared work and friendship led Hobbs across the Atlantic to join Moore as a secretary in a New York legal firm. In 1905 Hobbs boarded the Baltic and headed for America—coincidentally alongside Oswald Chambers (see pp. 11–13).

Their shared religious devotion was an easy talking point, but a new conversation began over the potential for professional (and personal) collaboration. As Oswald repeatedly told her, “I want us to write and preach; if I could talk to you and you shorthand it down and then type it, what ground we would get over!”

The two were married in 1910. Biddy joined Oswald on his preaching tours in America where she developed a dual vocation: preacher’s wife and secretary.

FROM SECRETARY TO LADY SUPERINTENDENT

In 1911 Oswald’s itinerancy stabilized in a permanent position as the head of the Bible Training College (BTC) in London. Mary Harris, widow of Richard Reader Harris and head of the League of Prayer, “had long been feeling the need for a Training College where scholarly teaching of the Bible would be given . . . and also where practical holiness would be taught and demonstrated” by Chambers himself. This hope was postponed during his bachelorhood. Now married, Oswald had “the helpmeet he needed.” With Biddy as “Lady Superintendent,” the Bible Training College opened its doors.

Biddy fused her professional skills with new opportunities in administration and education. As a “white blouse” revolutionary, she was the college’s central administrative engine and kept detailed notes of as many of Oswald’s teachings as she could. This role also gave her access to another working world: education. Women were considered to be naturally inclined toward nurturing the next generation and therefore capable of becoming educators. Forster’s 1870 Education Act expanded this professional opportunity for qualified women as new council schools across Great Britain required a large number of qualified teachers.

Biddy was not a trained teacher. However, Oswald considered her to be such an authority on the Psalms that she regularly lectured on the subject. She was one of many women in evangelicalism who found greater opportunity to teach and preach to audiences of both women and men, but as wife to the head of the BTC, she had unique access to a professional role that was unthinkable to her at the start of her secretarial career.

As the BTC grew, so did demand for greater access to Oswald’s teaching. Biddy translated her shorthand notes into typed pamphlets, then disseminated them through parachurch networks. The future, first imagined on the deck of the Baltic, came to fruition as Biddy’s notes-turned-text carried Oswald’s teachings beyond the doors of the BTC.

World War I relocated Oswald from London to Egypt, and he closed the BTC. By Christmas 1915 Biddy and daughter Kathleen joined him in the dusty huts of the camp and rebuilt their ministry of sermons and shorthand. When Oswald died suddenly, Biddy refashioned her dual vocation as secretary and wife to publisher and widow (see pp. 18–20; 24–26).

THE WORK GOES ON

Back in England Biddy Chambers entered a market ready to receive her religious publications. The book trade in interwar Britain was booming in the 1920s. Books were an accessible form of entertainment as well as religious teaching tools for the increasingly literate population. The Religious Tract Society published women writers like Nellie Hellis, Rosa Nouchette Carey, and editor Anne Hepple, who produced “wholesome” literature as an alternative to pulp fiction and romances frequently targeted at women.

Like these publishing women, Chambers struck out into the literary world to edify a Christian audience. A group of supporters formed the BTC Publishing Committee in 1922 to help connect her manuscripts to willing publishers.

Chambers typed and organized her notes into publishable works from the basement of her Oxford boarding house. She began the most significant of these—My Utmost for His Highest—in the early 1920s. After the success of this instant best-seller, the BTC Publishing Committee reorganized as the Oswald Chambers Publications Association to better support Chambers’s publication project and ensure financial stability. With this she effectively established her own publishing house.

After World War II and the end of wartime paper rationing, a new demand arose for Oswald’s words. Chambers frequently sent books to Bible colleges and missionaries in India, China, Italy, and the United States; even the Church of England requested permission to include various quotations in its devotional materials! Chambers indeed covered “such ground” through her publications, reaching the farthest corners of the mission field as well as the nooks and crannies of English churches.

WORDS OF "SPIRIT AND LIFE"

“My store of notes seems inexhaustible. ‘The trees of the Lord are full of sap.’ And the joy and privilege of the work increases as the years go by and letters come from all over the world telling of the way God is making the words ‘spirit and life’.”

Biddy wrote this in her 1934 biography of her husband, Oswald Chambers: His Life and Work. Compiled from memories of friends and Oswald’s own journals and letters, she published it to correct a case of mistaken identity: grateful readers consistently wrote to her as though she were Oswald himself! Though she published over 40 books and countless articles in Oswald’s name, Biddy never considered herself the author. As wife and secretary, she felt it was merely her duty to record and disseminate her husband’s words.

By her death in 1966, Biddy Chambers had transcribed nearly all of the notes taken during her marriage. Her 50-year publishing career was birthed out of grief, tested during war, and endured countless cultural transformations. Through it all the secretary gave her utmost to produce some of the most highly respected devotional publications in twentieth-century Christianity. CH

By Katherine Goodwin Lindgren

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #154 in 2025]

Katherine Goodwin Lindgren is assistant professor of women’s and gender studies at Hope College.Next articles

My search for Oswald Chambers

Discovering the man behind My Utmost for His Highest

David C. McCasland