Memory and preparation

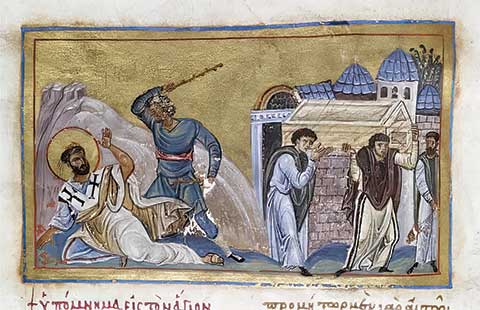

[Illumination of The Martyrdom of Saint Timothy, 11th Century, Byzantine. W.521, f. 203, v.—Walters Art Museum, Public domain, Wikimedia]

Sometime around the year 155 (or possibly 167), Polycarp, aged bishop of Smyrna and former disciple of John the Evangelist, was martyred by the Roman government. His martyrdom account, one of the earliest we have, states that his own disciples took his bones and placed them in “a fitting place”; there, they added, “the Lord shall grant us to celebrate the anniversary of his martyrdom, both in memory of those who have already finished their course, and for the exercising and preparation of those yet to walk in their steps.”

This is the earliest reference to honoring both the death date and the earthly remains of someone who had died for Christ. What began with Polycarp’s disciples meeting for prayer at his grave, grew, after the legalization of Christianity in the fourth century, into a much more systematic engagement with both the memory of saints and the relics (body parts and possessions) they were believed to have left behind.

RELICS AND SHRINES

Christians began to attribute miracles to the saints’ intercession and to nearness to their relics, and a devotion to the “cult of the saints” became a huge aspect of medieval Christianity. As historian Bryan Ward-Perkins notes:

Churches were built over their graves; pilgrims flocked to the major shrines, many of them seeking a specific remedy; saints’ relics were assiduously collected and distributed; their lives and miracle stories were written; altars, chapels and churches were dedicated to them; communities adopted them as their special protectors.

Saints were initially locally recognized (canonized) as worthy of veneration, especially on the date of their death, by bishops and other leaders; in 993 the pope began to make this determination for the Latin church, and in 1170 it became the pope’s sole prerogative.

The apostles were no exception to this process. All the apostles (except Judas Iscariot) are recognized today as saints with feast days in both Roman Catholicism and Orthodoxy, and numerous places became famous for having the apostles’ relics. (Relics were often moved for reasons of civic pride, fluctuating Christian control of Jerusalem and Constantinople, and the fear of lack of access for pilgrimage or desecration of

the relics.)

• St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome was erected over the apostle’s grave by Constantine; remains believed to be Peter’s were found there in the 1930s. Relics of Jude and Simon the Zealot, both believed to have been originally martyred in Persia, also rest at St. Peter’s.

• The basilica of St. Paul Outside-the-Walls in Rome possesses bones that it attests to be Paul’s.

• John’s grave in Turkey was covered by a succession of buildings, ending with a mosque that was destroyed in the fifteenth century. The tomb there is empty today.

• James the Less was buried in Jerusalem, but his relics were later moved to Constantinople and then Rome. Philip was buried in Turkey, but his relics, like James’s, went to Constantinople and then Rome, where the two are now interred together.

• Relics of Thomas are venerated in a basilica named for him in India, but a portion of them also went to Turkey and to a basilica in Ortona, Italy.

• Matthias’s grave was supposedly discovered in Jerusalem in the fourth century by Helena who took some relics to Trier, Germany, where they remain.

Devotion to all the saints, including the apostles, was both widespread and widely criticized; no matter how many times church leaders tried to distinguish veneration (i.e., reverence) for holy (but human) people from the worship due only to God, the history of medieval Christianity proves that many of the laypeople were not listening. The way that miracles had to be attributed to a holy person to launch the process of canonization, and the extensive practice of pilgrimage, were both processes that were easy to corrupt and exploit (see more on relics in issues #12 and #39).

Nevertheless beneath the centuries of structure and earthly power that grew up around the stories and relics of the apostles and thousands of other saints and martyrs, we can still glimpse the desire of those first disciples of the early church as they gathered around the grave of Polycarp two millennia ago: let us honor this person who followed Christ, and let us pray to be made like this person when our time comes to suffer too.

By Jennifer Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #156 in 2025]

Jennifer Woodruff Tait, senior editor, Christian HistoryNext articles

Sons of Alphaeus

Facts and myths About “brothers” Matthew and James, disciples of Jesus

Thomas G. Doughty Jr.“Doubting” or “daring” Thomas?

History’s most famous doubter recovered his faith and pioneered a bold mission to the East

Bryan M. Litfin