Courage, zeal, and faithfulness

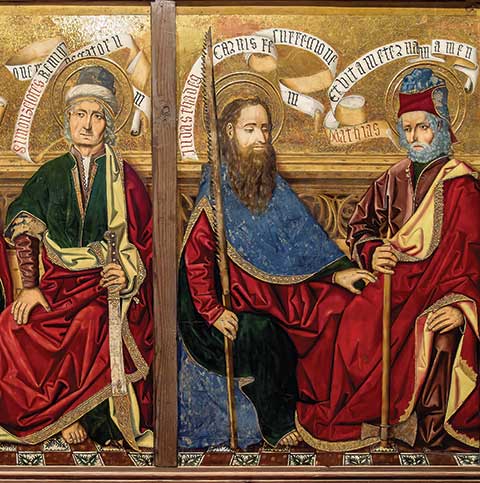

[ABOVE: Miguel Ximénez, Detail of Saints Simon the Zealot, Jude Thaddeus, and Mattias from Apostles and Annunciation. C. 1483 to 1487. Oil on panel—Zaragoza Museum, Spain / Public domain, Wikimedia]

Two of the remaining apostles always linked together are Judas Thaddeus and Simon the Zealot, both among the least known of Jesus’s disciples (see pp. 11–13). In Matthew 10:3 (King James Version), Thaddeus is listed as a surname for Lebbaeus; both of which are Greek versions of a Hebrew word meaning “beloved” or “courageous,” or possibly “big chested.” Judas Thaddeus speaks only once in the Gospels—a question in John (John 14:22–23). Simon is called “the Zealot” by Luke and “the Cananaean” by Mark and Matthew; the latter descriptor, instead of a geographical reference to Canaan, is an Aramaic translation of the Greek Zēlōtēs.

Matthias, chosen to replace Judas Iscariot, served as the new twelfth apostle; his election is reported by Luke in the first chapter of Acts. Mostly these three apostles receive only name mentions. Still each one is commemorated by various acts and tales of martyrdoms.

In his Church History, Eusebius mentions Thaddeus in a story about Abgar Uchama, the prince of Edessa, who allegedly sent Jesus a letter requesting him to come and heal his suffering (see p. 17). Abgar offered Jesus refuge, safe from the Jewish plots against him. Jesus declined Abgar’s offer but promised that, after his Ascension, he would send a disciple to Abgar to heal him. As a result Thomas took it upon himself to send his colleague, Judas Thaddeus, to Abgar.

Realizing that Thaddeus had come in response to his letter, Abgar confessed his faith in Jesus and the Father. Thaddeus placed his hand on Abgar in Jesus’s name, and the prince was healed immediately and miraculously, just as Jesus had healed the sick, without medicine and herbs. When Abgar asked for more information about Jesus, Thaddeus instructed him to assemble all the citizens of Edessa so that he could preach to everyone about Jesus’s mission, Crucifixion, Resurrection, and Ascension. Later Christians of Edessa pointed to Thaddeus’s mission as their church’s founding.

Judas Thaddeus and Simon the Zealot are paired together in a late story of martyrdom preserved supposedly by Bishop Abdias of Babylon. In the Acts of Simon and Jude, these two apostles partnered in a mission to Persia to the east of Edessa. There Judas and Simon encountered two magicians, Zaroës and Arfaxat, whom the apostle Matthew had driven out of Ethiopia. These Persian magi were Manichaeans, teaching that the God of the Old Testament was the god of darkness, that the body is evil and only the soul is good, and therefore, that the incarnation of Christ was in appearance only.

Proceeding further into Persia, the apostles and the magicians met General Varardach, leader of Xerxes’s army, preparing for battle with India. He asked for a prediction, and the magicians prophesied a great battle with many casualties—a likely scenario. But the apostles retorted that the Indians would sue for peace and submit to Persia. When the apostles’ prophecy came true, Varardach threatened to execute the false magicians, but the apostles interceded for their opponents’ lives. Once freed, however, the magicians continued to slander the apostles, sowing lies among the people.

CHOOSING THE PALM

Nonetheless Thaddeus and Simon remained in Persia, preaching throughout the empire. They healed the sick and performed many miracles. In Babylon alone they converted 60,000 new believers and ordained new ministers, including Abdias. The final ministry for Thaddeus and Simon occurred at a temple dedicated to the sun and moon, which the Persians worshiped. Zaroës and Arfaxat aroused the people to demand that the apostles sacrifice to the gods or be executed. The apostles, however, preached that the true God whom they serve created the sun and moon, and they proceeded to exorcise the temple’s demons. Although two demons, appearing as gruesome black figures, fled the temple, the people attacked the apostles.

Judas then said to Simon: “I see the Lord calling us.” Simon replied: “I see him also among the angels.” An angel then gave the apostles a choice: either the death of all present, or the palm of martyrdom (the palm was a symbol for such a death, as referenced in Revelation 7:9 and seen in martyr icons). According to the Acts, “they chose the palm.”

The deaths of Judas and Simon were described variously as being effected by sticks and stones, or by swords and spears, with Simon additionally being sawn in two. In St. John Lateran Basilica in Rome, Judas is depicted with a spear (more specifically, a halberd) and Simon with a saw.

GIFT OF GOD

After Judas Iscariot died, the other apostles needed to choose another disciple to complete the Twelve (see p. 49). Matthias, whose name means “gift from God,” served as the providential replacement. But the New Testament says little of Matthias after this: Luke writes that he had accompanied the Lord Jesus from his baptism to his Resurrection and Ascension (Acts 1:21–26). Once he was elected as an apostle, he would have served alongside the other 11 during the preaching at Pentecost (Acts 2:4, 37), the ministries of teaching and praying (Acts 2:42–43), and the persecutions instigated by the Sanhedrin and Saul (Acts 5:18, 40; 8:1). According to Eusebius, Matthias had originally been included among the 72, the larger group of Jesus’s disciples.

IMAGINING MATTHIAS'S MINISTRY

One of the earliest accounts of Matthias’s mission work is the Acts of Andrew and Matthias. In this story Matthias was assigned to preach in Myrmidon, the Scythian city of cannibals. When he entered the city, the pagans drugged, blinded, and imprisoned him, intending to eat him in three days. Jesus, however, appeared to Matthias, healed him, and promised to send Andrew to him. Andrew arrived and rescued his fellow apostle, and together they healed other blinded men in prison. Andrew remained for a time in Myrmidon, but a cloud appeared and took him and Matthias to a city to the east where they met up with Peter.

Another Eastern tradition claims that Matthias and Simon teamed up with Andrew on a mission to Georgia, located to the west of modern-day Russia. In Asparos, Georgia, a gravestone marks the spot of Matthias’s alleged death and burial.

With so little known about Matthias, writers felt free to invent details. For example a late account from a Byzantine historian claimed that Matthias journeyed to Ethiopia. There he preached and then died as a martyr by crucifixion. Hippolytus of Rome wrote, however, that Matthias died naturally: “And Matthias, who was one of the Seventy, was numbered along with the eleven apostles, and preached in Jerusalem, and fell asleep and was buried there.” In another tradition Matthias was stoned to death by the chief priests and Pharisees in Jerusalem. Still others claim that he died by axe or lance.

One fantastic legend by Abdias records that Matthias preached in Damascus, where the men of the city seized him and tried to burn him alive on a griddle. He endured this torture for 25 days. The citizens finally declared that Jesus must be a mighty God. Through Matthias’s survival many converted. The new Christians tore down idols, razed temples, and built a church. Abdias concludes: “After this preaching and proclaiming of good news, he slept a good sleep and rested from his labors in the city of Phalaon, which is among the cities of Judah.”

From these varied and contradictory traditions, we see that very little can be known for certain about Matthias’s later ministry and death. Most likely he evangelized in Jerusalem with his fellow apostles and then traveled beyond Judea, possibly to Damascus, Myrmidon, Georgia, or Ethiopia. Whether Matthias died of natural causes or as a martyr, he was at the least a confessor, who remained a faithful witness to his Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ.

Despite the obscurity of these three apostles, churches still sought prestige from their memories by claiming their evangelization of the region or their martyrdoms nearby. In spite of conflicting stories and various accounts of martyrdoms, we can be certain that early Christians honored the memories of these apostles. CH

By Rex D. Butler

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #156 in 2025]

Rex D. Butler is recently retired as professor of church history and patristics at New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary.Next articles

Acts of Paul

Anonymous; translated by Bryan M. LitfinWomen of the Way

Who were the women who followed Jesus, and what roles did they play in the fledgling church?

Rex D. Butler