Reformers of Rome

[Jacques Maritain—Public domian, Wikimedia]

JOHN HENRY NEWMAN, CONVERTED CARDINAL (1801–1890)

Born in London to a banker father and a mother with Huguenot ancestry, John Henry Newman began his faith journey as an evangelical Christian with deep Calvinist leanings.

He attended Oxford and was ordained as an Anglican priest in 1825, and throughout the years became more convicted of church authority. In particular he sought to purge all nonconformists (Protestants who did not want to conform to the Church of England’s governance model) from the Church Missionary Society, of which he was then secretary. Newman later became an activist in the Oxford Movement.

By 1842 Newman had withdrawn to a community in Littlemore, where he lived a semimonastic life with other like-minded Anglicans. Slowly these men converted to Catholicism, and Newman was received into the Roman Catholic Church on October 9, 1845. Eventually he settled into a religious community outside Birmingham, where he served for almost 40 years, first as a priest and then as a cardinal.

Newman was passionate about scriptural theology and the theology of the ancient church fathers. This contrasted with the emphasis on scholastic theology typical of mid-nineteenth-century Roman Catholicism. Newman, who some consider the most important Catholic convert since the Reformation, was alive during the First Vatican Council and is sometimes referred to as “the father” of the Second.

Pope Leo XIII named John Henry Newman a cardinal in 1879. Newman died in 1890 at age 89 and was canonized in 2019 by Pope Francis. Pope Leo XIV proclaimed him Doctor of the Church in 2025.

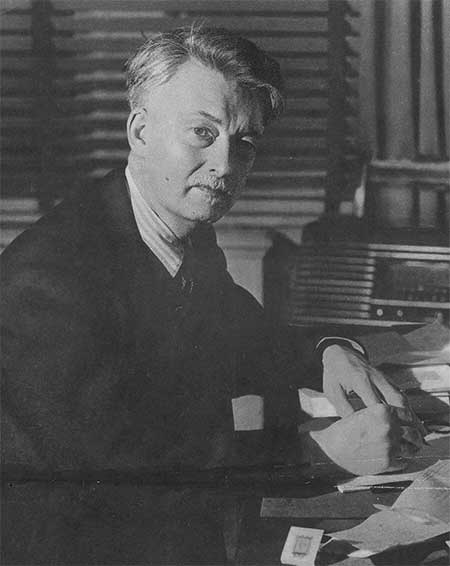

JACQUES (1882–1973) AND RAïSSA MARITAIN (1883–1960), INTEGRAL HUMANISTS

Jacques Maritain and Raïssa Oumansoff came together as young students at the University of Paris. Jacques was the descendant of a prominent French politician, Raïssa the daughter of Jewish immigrants. The purely materialistic philosophy they were learning left them unsatisfied. They concluded that if they found nothing to meet their hunger, they would kill themselves. Through Catholicism they discovered the spiritual reality they sought. They married in 1904 and were baptized in 1906. After their conversion, first Raïssa and then Jacques discovered Thomas Aquinas, whose philosophy would be central to their work.

Jacques Maritain used the phrase “integral humanism” to express the Christian understanding of human dignity as people made in God’s image, and this exercised a significant influence on Vatican II. Involved in the right-wing Action Francaise movement in the 1920s (see p. 21), Maritain rethought his far-right position due to the pope’s condemnation. He came to see democracy as the best expression of Christian beliefs about human dignity. Rather than seeking dominance, as the church had historically done, Catholics should take part in democratic societies as partners alongside nonbelievers, working for justice.

The Maritains spent the war years in Canada and the United States, where Jacques taught philosophy while denouncing the Vichy government and working to help refugees fleeing the Nazis. After the war Jacques became French ambassador to the Vatican and attended the UNESCO conference in 1947 that drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. His thought influenced many, including Martin Luther King Jr. (1929–1968). Raïssa died in 1960; Jacques lived with the Little Brothers of Jesus in Toulouse, France, until his own death in 1973.

HENRI DE LUBAC, NEW THEOLOGIAN (1896–1991)

Henri de Lubac was born in Cambrai, France, to an aristocratic French family. He attended a Jesuit school and joined the Society of Jesus at age 17. In 1914, de Lubac was drafted into the French Army during the beginning of World War I. After being discharged in 1919, de Lubac continued his theological education in both France and England, and he was ordained a priest in 1927.

In 1929 de Lubac became a professor of fundamental theology at the Catholic University of Lyon, where he taught until 1961. With the rise of Nazism, de Lubac began to write for an underground journal resisting the Nazi regime called Christian Testimony. These dissident writers asserted the many ways Christianity was discordant with the regimes set up in both Germany and Vichy France. Throughout much of World War II, de Lubac was in hiding, but he continued to write even as other cowriters were captured and killed.

In June 1950 Jesuit superior general Jean-Baptiste Janssens ordered that some of de Lubac’s publications be removed from all Jesuit libraries, due to his promulgation of nouvelle théologie (see pp. 17–20). Pope Pius XII later issued an encyclical against modernism, which heavily implied an attack on nouvelle théologie, and the church did not allow de Lubac to return to his professorial role until 1958.

His favor changed 10 years after his original censure. In 1960 Pope John XXII made de Lubac a consultant, then a theological expert, and finally a member of the Theological Commission for the Second Vatican Council. Two of de Lubac’s ideas were particularly influential on the council. One was the insight that the church is the Body of Christ as a community gathered around the Eucharist, so that “the Eucharist makes the Church.” The other was his denial of a sharp distinction between nature and grace, so that all of human life was seen as ordered toward the vision of God.

De Lubac later cocreated the journal Communio with Joseph Ratzinger and became a cardinal in 1983. He died in 1991 in Paris at the age of 95.

JOHN COURTNEY MURRAY, CONSTITUTIONAL CATHOLIC (1904–1967)

Born in New York City, John Courtney Murray entered the New York Province of the Society of Jesus as a teenager in 1920. Ordained as a priest in 1933, Murray earned his doctorate in 1937 from Georgetown. The same year he became a professor of theology at the Jesuit seminary Woodstock College in Woodstock, Maryland, and was named editor of the journal Theological Studies in 1941. He maintained his professorship and role as editor until his death.

In addition to specializing in trinitarian theology, Murray was interested in the intersection of the church and pluralism: how can Catholicism flourish in a modern, pluralistic society? He believed that the US Constitution was correct in both limiting government’s power and separating church from state. He believed constitutionalism gave people their own moral agency over their faith instead of relying on top-down paternalistic structures, and he presented his views in We Hold These Truths: Catholic Reflections on the American Proposition. The idea that a “new moral truth” could be wrought outside of the Roman Catholic Church was too far for the Vatican at the time, however. The Vatican forbade Murray from publishing his last two articles on the subject.

However, almost a decade later, the Vatican invited Murray to the second session of the Second Vatican Council. He worked on his document for religious freedom, and in 1965, the council officially endorsed his work in Dignitatis Humanae Personae. The document articulates the church’s support for secular states to have religious freedom. The final document states, “Religious freedom . . . which men demand as necessary to fulfill their duty to worship God, has to do with immunity from coercion in civil society.” Murray continued working and writing until his death from a heart attack in 1967. He was 62.

KARL RAHNER, PHILOSOPHER THEOLOGIAN (1904–1984)

Karl Rahner was born in Freiburg, Germany, in 1904 and lived a largely uneventful life dedicated to writing, teaching, and pastoral ministry. He joined the Jesuit Order in 1922 and worked as a theology professor at various Austrian and German universities for most of his life. He also wrote prolifically, producing thousands of works during his career. This quiet life was the basis for an adventurous theology. Rahner integrated the theology of Thomas Aquinas with the philosophy of Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) and Martin Heidegger (1889–1976). He taught that our very existence is a manifestation of God’s grace and that we have a fundamental awareness of God beyond words and concepts; people who respond to God’s manifestation of himself within their hearts are, in Rahner’s terms, “anonymous Christians.”

When Vatican II began, Rahner was under “pre-censure” by the Vatican and the Jesuit Order, which meant that he was not allowed to publish anything without prior approval. He was not initially invited to be one of the scholar-experts advising the bishops, but Pope John XXIII appointed Rahner as a theological consultant. From being a theologian under a cloud, Rahner became one of the most influential figures at the council, and his concept of “anonymous Christians” in particular influenced how the church spoke of the salvation of those outside the faith. In 1984 Rahner fell ill and died, just after his eightieth birthday. This prayer of Rahner’s summarizes his life’s work: “You are the first and last experience of my life. Yes, really You Yourself, not just a concept of You, not just the name which we ourselves have given to You!”

YVES CONGAR, ECUMENICAL REFORMER (1904–1995)

Yves Congar was born in France and experienced most of his childhood under German occupation during World War I. He entered seminary as a youth and, after a short stint of required military service, joined the Dominican Order at Amiens. He was ordained as a priest in 1930 and wrote his dissertation on the unity of the church.

Congar was a professor at Le Saulchoir, a Dominican school, from 1931 to 1939, where he taught theology and ecclesiology. When World War II broke out in Europe, Congar was drafted as a chaplain in the French Army. The Germans captured and held him as a prisoner of war from 1940 to 1945, during which he attempted many failed escapes. Following his release, he was awarded numerous medals for bravery.

After the Second World War, Congar continued his theological work and teaching. He increasingly focused on ecumenism and encouraged collaboration and understanding among the Roman Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, and Protestants. He criticized what he viewed as overextended papal powers and advocated for stronger lay leadership within Catholicism.

The Vatican limited Congar’s writings from 1947 to 1956, especially his 1950 book True and False Reform in the Church. In 1954 he was banned from teaching or publishing by Pope Pius XII. The tide turned under Pope John XXIII, however, as Congar was invited to participate in the Second Vatican Council. In retrospect numerous Catholic thinkers believe that of all the Catholic theologians who took part in Vatican II, Congar had the most influence. He participated in primary writing roles on some of the most important conciliar documents, including Unitatis Redintegratio (see pp. 35–37), which was close to Congar’s heart.

In 2021 Pope Francis said before the formal opening of the Synod on Synodality, “There is no need to create another church, but to create a different church.” These words were from Congar’s once-disregarded True and False Reform in the Church. Made a cardinal deacon before his death, Congar once said, “I am a man of tradition. This does not mean I am a conservative. Tradition, as I understand it, is like the Church itself: It comes from the past but looks forward to the future and sets the stage for a new eschatology.” He died at the age of 91.

THOMAS MERTON, RADICAL MONK (1915–1968)

Thomas Merton was born in France to a father from New Zealand and an American mother; both were artists. Merton was likely baptized in the Church of England per his father’s wishes, but of this, Merton had no proof. When he was still an infant, the family moved to Queens, New York, due to World War I. He was 6 when his mother died of cancer and 15 when he lost his father to a brain tumor.

After a brief and unhappy stint at Clare College, Cambridge, Merton returned to the United States to study at Columbia University. Shortly after graduating in 1938, Merton met and was impressed with Hindu monk Mahanambrata Brahmachari (1904–1999). Instead of encouraging Merton to explore Hinduism, however, Brahmachari encouraged the young man to reestablish his connection with Christianity. Merton was baptized as a Roman Catholic at Corpus Christi Church in New York later that year, and by 1941, had joined the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance. Now a Trappist monk in the most ascetic Catholic order, he began his ministry at the Abbey of Gethsemani near Bardstown, Kentucky.

Merton was a prolific writer; his most famous book was The Seven Storey Mountain, his 1948 autobiography. He also strongly supported the American civil rights movement, believing that race and peace were the most important issues of his time. He described the nonviolent movement as “certainly the greatest example of Christian faith in action in the social history of the United States.”

As the tumultuous 1960s played out in the United States, Vatican II was also in session. Though Merton had qualms about where the church would ultimately land after the council, he was most concerned with war, peace, and the church’s view and treatment of non-Christian religions. But ultimately Merton agreed with John XXIII’s ideas and ideals, writing in 1965 ahead of the final council that the Catholic Church’s task is “proclaiming the Gospel of love and hope to modern man in a language that he will understand, without any alteration or distortion of the essential Gospel perspectives.”

Though not without controversy, Merton remained a devoted Trappist monk for 27 years. He died in Bangkok, Thailand, at a monastic conference in 1968. He was 53.

JOSEPH RATZINGER, CONTINUITY POPE (1927–2022)

Born in Germany, Joseph Ratzinger attended seminary starting at age 12 until his school was closed for military use in 1942. Ratzinger’s father was a police officer, despised the Nazi regime, and he was continuously demoted as a result. At the age of 14, Ratzinger was conscripted into the Hitler Youth, but he often refused to attend meetings. Forced to participate in the German infantry, Ratzinger was captured by Americans as a prisoner of war. He was released on June 19, 1945, and resigned his post.

After the war Ratzinger and his brother attended Saint Michael Seminary and were ordained on the same day in 1951. Ratzinger also studied philosophy at the University of Munich, where he was a curate before moving on to professorships in both Bonn and Münster. From 1962 to 1965, Ratzinger was asked to participate in the Second Vatican Council. He was considered part of the church reform movement of nouvelle théologie. Ratzinger was concerned with the pope’s profound authority, liturgy, religious freedom, ecumenism, and how the Catholic Church approached the secular world around it.

Though during the 1960s many viewed Ratzinger as a progressive, Catholic thinkers today believe “progressive” is a misnomer in context. Ratzinger was interested in going back to the sources of the early church fathers and the Bible itself, while separating the Catholic Church from the dry neoscholasticism so popular the century before. When he was accused of having morphed into a conservative in the 1990s, Ratzinger responded, “I see no break in my views as a theologian.”

When he was elected Pope Benedict XVI in 2005, Ratzinger carried this view with him as he sought continuity with the pre-conciliar church. He served until his resignation in 2013 due to poor health. He was the first pope to resign in almost 600 years. He died in 2022 at the age of 95.

HANS KÜNG, LIBERAL ADVISOR (1928–2021)

Swiss-born Hans Küng was the youngest of the periti at Vatican II—the scholar-experts who advised the bishops. He was also the most radical of the major theologians at the council. His 1960 book The Council and Reunion correctly predicted many of the directions the council would take, but the council failed to live up to Küng’s hopes. In particular he had hoped that the council would lead to reunion with Protestants.

Küng wrote his doctoral dissertation on Karl Barth, and was convinced, like Rahner, that Protestant theology was not fundamentally incompatible with Catholicism. However, while Rahner became the voice of the post–Vatican II consensus, Küng faced censure after his explicit denial of papal infallibility in 1971. Küng argued that the church was “indefectible” rather than infallible. God would never abandon the church, but no specific church teaching could be enshrined as beyond question.

Rahner expressed sympathy with Küng’s criticism of papal authority but believed he went too far in denying infallibility altogether. In 1979 Küng’s former colleague Joseph Ratzinger, acting as prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, stripped Küng of his license to teach Catholic theology. The University of Tübingen responded by making Küng’s Institute for Ecumenical Research independent of the Catholic theology faculty, and Küng continued to teach there until he retired in 1996.

Küng’s condemnation made him a hero for liberal Catholics and a symbol of dashed hopes for more radical church change. Küng’s Christology was also controversial, since he spoke of Jesus in primarily human terms and was accused of downplaying or even denying his divinity. He also criticized priestly celibacy, advocated a liberalization of church teaching on sexuality, and defended the legitimacy of euthanasia under some circumstances. CH

By Jennifer A. Boardman and Edward Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #157 in 2025]

Jennifer A. Boardman is a copyeditor and writer. She holds a master of theological studies from Bethel Seminary with a concentration in Christian history. Edwin Woodruff Tait is a contributing editor to CH and scholar advisor of this issue.Next articles

Recommended resources: Vatican II

Learn more about the Second Vatican Council with these resources written and recommended by our authors and editors.

the editors and authors