Really God, really human

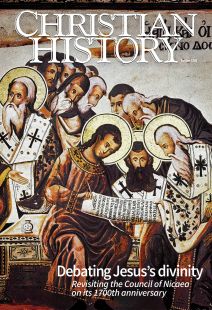

[ABOVE: A medieval manuscript imagines the Spirit-inspired apostles composing the Apostles’ Creed. Laurent d’Orléans, Illustration Comment li apostre font la credo in La Somme le Roi. 1279. MS 54180, f.10v—British Library / Public domain, Wikimedia]

If you grew up, as I did, in the 1970s mainline, you may not have thought a lot about creeds. I vaguely remember saying the Apostles’ Creed in the United Methodist church I attended. I also remember saying “A Modern Affirmation” equally as often and sometimes using what is usually referred to as the “Statement of Faith of the Korean Methodist Church.” It was Anglicanism that taught me the creeds—though at that point, no one talked about them any more than the Methodists had.

When I began attending Episcopal churches off and on in the late 1990s, I realized that creeds were part of every worship service I attended—the Apostles’ Creed at Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer and the Nicene Creed at Holy Eucharist. While no one knows the exact date the Apostles’ Creed came into use in something resembling its current form (the best we can do is the early Middle Ages, see “Did you know?”), we have a date and place for the Nicene Creed. It is named after the city where the council that produced its initial form took place: Nicaea. It was there that it was also adopted in 325.

The version we say today is not exactly that one. It was officially altered at some length at the Council of Constantinople in 381, mainly by adding much more material on the Holy Spirit, and—in the West—it was changed in a shorter but more controversial way during the High Middle Ages with the addition of the phrase filioque (and the Son) to the description of the Spirit’s procession from the Father (p. 12).

Nevertheless, what Anglicans worldwide recite in church every Sunday, allowing for translation into local languages, is visibly and unbrokenly still, basically, the same thing agreed on in council 1,700 years ago. For some, that fact—the 1,700 years separating us from people who were, after all, fallible human beings and who lacked the hindsight of all those centuries of enlightening history that we now possess—is enough to cast doubt on the significance of this anniversary. How can anything that old, that supposedly narrow-minded, that entwined with the realpolitik of its age (and it was entwined, as this issue has shown), possibly speak to the problems of the twenty-first century? For others—and I will lay my cards down on the table and admit that I am in this camp—the 1,700 years are the feature, not the bug.

So great a cloud of witnesses

What began to move me through those steady decades-long series of Eucharists, as I repeated the creed over and over, was the fact that I was rehearsing words said by so many others throughout the world and down through the ages to testify to their faith in the Christian God, and to describe—insofar as such a thing is even possible—what the Christian God is like. People had said these words in sadness and joy, wealth and poverty, on the decks of ships and in hidden upstairs rooms, in beautiful cathedrals, and at my church in rural Kentucky with an average Sunday attendance of 22 people. People had even died for them sometimes.

The Nicene Creed is not inspired Scripture. Only Scripture is Scripture. But the creed represents what the best theological minds of the early 300s came up with when they wrestled with seemingly irreconcilable things the inspired Scriptures told them about: a God who is powerfully and ineffably One, yet a God who became utterly and completely human. Somehow, Jesus of Nazareth is both “Light of Light, very God of very God,” and a human being who “suffered under Pontius Pilate.” He is the one “by whom all things were made” and yet also the one “who came down from heaven . . . and was made man.” As Jane Williams said in Seen & Unseen, an online cultural and theological journal:

There are not many 1,700-year-old documents that are read out loud every week and known by heart by millions of people across the world. . . . The radical suggestion of the Nicene Creed, trying to be faithful to the witness of the Bible, is that Jesus is really God, living among us, but also really a human being, born into a particular time and place in history and dying a real, historical death. And that must mean that the Almighty God doesn’t think it compromises God’s power and majesty to come and share our lives.

Yes, those best theological minds were quite possibly only sitting in council there in Nicaea in the first place because an autocratic emperor told them to get their theological messaging in order because their infighting was interfering with Christianity’s usefulness to empire. God has worked with less, sometimes. Yes, occasionally individual lines in the Nicene Creed strike me (and other modern people) as funny, and we wonder if we still believe them. While we’re wondering, the universal church still believes them for us. You can wander a lot of places in your life and think a lot of things. The Nicene Creed will still be there when you get back.

So, on this anniversary, I urge you to think about the Nicene Creed not as narrow-minded but broad, speaking to us of grace and Christian community. The creed reaches backward in time over millennia and goes all the way around the globe. It testifies to a God who walks beside us into an unknown future—both as the One who will finally set all things to rights and as our friend and brother. And that, I think, is well worth celebrating.

CH

By Jennifer Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #158 in 2026]

Jennifer Woodruff Tait is senior editor of CH, editor for the Theology of Work Project, and an episcopal priest in the Diocese of Lexington. This reflection, originally featured in Anglican and Episcopal History 94.3 (June 2025), is reprinted with permission.Next articles

Recommended resources: CH158 Nicaea

Study the Nicene council, its creed, and the figures around it with these resources written and recommended by our authors and editors.

the editors