State of Emergency

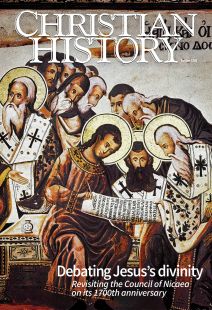

[ABOVE: Michael Demaskinos, The First Council of Nicaea. 1591. Agia Collection, Heraklion, Crete—C Messier / Public domain, Wikimedia]

Graffiti emblazoned on walls, a vicious war of pamphlets, riots in the streets, lawsuits, catchy songs of ridicule—this was the tumultuous atmosphere in which fourth-century Christians found themselves. For modern believers (and those with a tendency to romanticize the early church as a picture of perfect unity), such public turmoil created by an argument between theologians can be difficult to imagine. Moreover, how could God work through the messiness of this human conflict to bring the church to an understanding of truth?

To us, in retrospect, the Council of Nicaea is a mountain in the landscape of the early church. For the participants themselves, it felt more like an emergency meeting forced on hostile parties by imperial powers and designed to stop an internal squabble. After the council, many of the same bishops who had signed its creed appeared at other councils, often reversing their previous decisions according to the way the winds of government or church preference were blowing. They found themselves less in a domain of monumental clarity and more in a swamp of confusing arguments and controversies that at times seemed to threaten the very continuity of the Christian church.

To understand the significance of the Council of Nicaea, we need to enter into the minds of the disputants and ask why so much bitterness and confusion had been caused by one apparently simple question: In what way is Jesus divine?

Of course, like many “simple” questions, this was actually a highly complex and provocative issue. Theologians were almost beside themselves when they found that Scripture often gave very different-sounding notes when they applied to it for guidance. The disagreements this question provoked made many of the greatest minds of the era wonder to what extent the Christian doctrines of God, Christ, and the Holy Spirit were coherent and even to what extent Christians could trust in the canon of sacred text (which had hitherto seemed to them sufficient as an exposition of the faith).

Rather than being a symbol of clarity, peace, and order, the council called for difficult and messy work: a focusing of Christian thought across a church often as muddled and confused as ours still seems to be.

The Lord is one

The argument began innocently enough with a regular seminar that Alexander, the archbishop of Alexandria (250–326; see pp. 36–39), was accustomed to hold with his senior clergy.

Alexander was a follower of Origen, who lived a century before him. Origen had laid the basis for a vast mystical understanding of the relationship of the divine Logos to the eternal Father. Logos, the word the Greek Bible had used to translate “divine wisdom,” was also widely used in Greek philosophical circles to signify the divine power immanent within the world. To many Christians it seemed a marvelous way to talk about the eternal Son of God and became almost a synonym for the Son.

Like Origen, Alexander saw the Logos as sharing the divine attributes of the Father, especially that of eternity. The Logos, Alexander argued, had been “born of God before the ages.” Since God the Father had decided to use the Logos as the medium and agent of all creation (e.g., John 1:1, Eph. 1:4, Col. 1:15–17), it follows that the Son-Logos must have preexisted creation. Since time is a consequence of creation, the Son preexisted all time and is thus eternal like the Father, and indeed his timelessness is one of the attributes that manifests him as the divine Son, worthy of the worship of the church. Since he is eternal, there could be no “before” or “after” in him. It is inappropriate, therefore, to suggest that there was ever a time when the Son did not exist.

God is eternally a Father of a Son, Alexander argued, and just as the Father had always existed, so too the Son had always existed and is thus known to be “God from God.” The Christological confessions developed from Scripture about the Son (later to be inserted into the creed of Nicaea) make this all clear: “Born not created, God from God, Light from Light, True God from True God.” It is at once a high and refined scholarly confession of the faith and a popular prayer that sums up how Christians can be monotheists even as they worship the Son along with the Father.

Alexander knew he would face resistance from his church by saying that Christ’s divinity could no longer be understood in the old simplistic ways of a “lesser divinity” alongside a “greater divinity.” Alexander wanted to distinguish clearly between Christian and pagan theology by arguing that “divinity” is an absolute term (like pregnancy) that allows no degrees. One cannot say that the Son is “half God” or “part God” without making the very notion of deity into a mythical conception.

Given Alexander’s clarification, many traditional Christian pieties would need to be reforged in the fourth century. People sensed that they were on the cusp of a major new development—but they were not always quite sure what was happening, and more to the point, they lacked a precise or widely agreed-upon vocabulary to explain to themselves (and to others) what exactly was going on.

One of Alexander’s senior priests, the presbyter Arius (256–336), was scandalized at the direction in which his bishop was taking theological language. Arius, who had charge of the large parish of Baucalis in the city’s dockland, had also been an intellectual disciple of Origen, but had taken hold of a different strand of that early theologian’s variegated legacy.

Theological Niceties—or the Essence of Christianity?

As was typical among third-century thinkers, Origen had a deeply ingrained sense of the absolute primacy of God over all other beings. This means that the Father is superior to the Son in all respects—in terms of essence, attributes, power, and quality. The Son might be called divine insofar as he represents the Father to the created world as the supreme agent of the creation (something like one of the greatest of all angelic powers), but he is decidedly inferior to the Father in all respects. This means that the Son does not possess absolute timelessness, a sole attribute of God the Father.

Thinking that he was defending traditional values, Arius pressed this view of Origen’s even further. The Son-Logos, Arius allowed, might well have predated the rest of creation, but it is inappropriate to imagine that he shared the divine preexistence. Thus, Arius confessed the principle that “there was a time when he (the Logos) was not.” Arius quickly put this axiom into a rhyme, which he taught his parishioners and so made it into a party cause. Soon slogans were ringing round the dockland, and the diocese of Alexandria was in serious disarray. Arius’s supporters chanted, “Een pote hote ouk een” (there was a time when he was not) and wrote the slogan on the walls. Overnight Alexander’s camp added a Greek negative to the beginning: “Ouk een pote hote ouk een” (There was never a time when he was not).

Everyone, skilled theologian or not, seemed to have been caught by surprise that a controversy over so basic a matter (is the Son of God divine? And how?) could have arisen in the church and even more surprised that recourse to Scripture was proving so problematic. For every text that shows the divine status of the Son (“I and the Father are One,” John 10:30; “And the Word was God,” John 1:1), another can be quoted back to suggest the subordinate, even the created, status of the Son (“In the beginning he created me [Wisdom],” Prov. 8:22; “Why do you call me good? No one is good but God alone,” Mark 10:18). If Jesus is not fully God, he is not really God at all, and thus to worship him is not piety but simply idolatry.

Alexander (applying good pastoral sense) would not allow a theological dispute to mushroom out publicly in this alarming way, so he censured Arius for appearing to deny the Son’s eternity and true divinity and deposed him from his priestly office. Arius immediately appealed against that disciplinary decision to one of the most powerful bishops of the era, Eusebius of Nicomedia, a kinsman by marriage to Constantine the emperor. Arius and Eusebius had been students together and shared a common theological view. Eusebius, the court theologian at the imperial capital, knew that if Arius was being attacked then so was he. From that moment onward, he was determined to squash what he regarded as a “foolish Egyptian piety.” By elevating the Son of God to the same status as God the Father, he argued, Christianity would compromise its claim to be a monotheist religion. Eusebius marshaled many supporters.

The bitterness of the dispute seemed remarkable to many observers, but what was at stake was no less than a major clash between two confessional traditions that had been uneasy companions in the church for generations. One tradition stressed the subordination of the Son (Christ the Servant of God). The other emphasized the salvific triumph of the Savior (Christ the Lord of Glory in his most intimate union with the Father).

So notorious had the falling out of Eastern bishops become over this matter that it was brought to the attention of Emperor Constantine (d. 337) who, in 324, had defeated his last rival to become sole monarch of all the Roman Empire. Constantine decided to use the occasion of the twentieth anniversary of his claiming of the throne in 306, which would be celebrated in 325, to help settle the embarrassing dispute among his allies, the bishops. He felt (rightly) that their disarray compromised his desire to demonstrate that he had effectively “brought peace” to the eastern territories.

The Anniversary Council

So it was that he summoned bishops to his private lakeside palace at Nicaea (Victory City) in Asia Minor (now Iznik in Turkey), offering to pay all their expenses, to supply them with the traditional “gifts” that followed an invitation to the court, and even to afford them the prestigious use of the official transport system, a privilege that had always been strictly reserved for officers of state. The buzz this created was all the more remarkable among the bishops of the East, who only a year or so before had lived under a persecutor’s oppression.

Though Constantine envisaged a truly international meeting of minds, in fact very few Latin bishops attended—only representative delegations from leading sees such as Rome.

Some sources say the council opened on June 19. Tradition has it that 318 clergy were in attendance, but many modern historians think that 250 is a more accurate figure (see “Did you know?”). As the meeting opened, Constantine took his place on the imperial throne and greeted his guests. He spent the opening session accepting scrolls (secret petitions for favors and for redress) from the many bishops in attendance and then startled them all the next day by bringing in a large brazier and burning the whole pile of scrolls before them—saying enigmatically that in this way the debts of all had been cancelled. By this he implied that most of the petitions from the bishops were aimed at one another, and rather than put many on trial, he gave a common amnesty.

The order of the day was to resolve the question about the eternity and divine status of the Son of God. Many of the bishops were not well educated, but a few of them were highly skilled rhetoricians and theologians, and they were determined that if anything theological was to be settled by the large council, it would be in favor of the pro-Alexander lobby.

For this reason they pressed for a refinement of the baptismal creed of Jerusalem, which had been submitted by Eusebius of Caesarea as a blueprint for a “traditional statement of faith.” Eusebius had been deposed at an earlier synod for having publicly attacked Alexander’s theology. Under pressure from Constantine, the assembly at Nicaea pardoned him and restored him to office after he offered the creed of his own church as evidence of his change of heart.

All the bishops recognized how unarguably “authentic” this statement of faith was, but the Jerusalem creed did not really resolve the precise issue under consideration: that is, how the Son of God relates to the divine Father. To this end the bishops decided that extra clauses would be interpolated into the old creed as “commentary,” to amplify the bare statements about the mission of Christ and to show how Jesus could be confessed as God. Alexander’s party had originated these “confessional acclamations” of Christ (“God from God, Light from Light,” etc.), but since it had become clear that even their opponents could accept Christ’s title as “god from God” (as meaning a nominal, inferior deity from the superior, absolute deity), many of the Alexandrians demanded a firmer test of faith.

Creed and catchword

It was possibly Ossius (256–359), the theological adviser of the emperor, who suggested that the magic word to nail the Arian party would be homoousios. The term means “of the same substance as,” and when applied to the Logos, it proclaims that the Logos is divine in the same way as God the Father is divine (not in an inferior, different, or nominal sense). In short, if the Logos is homoousios with the Father, he is truly God alongside the Father. The word pleased Constantine, who seems to have seen it as an ideal way to bring all the bishops back on board for a common vote. It was broad enough to suggest a vote for the traditional Christian belief that Christ is divine, it was vague enough to mean that Christ is of the “same stuff” as God (no further debate necessary), and it was bland enough to be a reasonable basis for a majority vote.

It had everything going for it as far as the politically savvy Constantine was concerned, but for the die-hard Arian party, it was a word too far. They saw that it gave the Son equality with the Father without explaining how this relationship works. (In fact it would be another 60 years before anyone successfully articulated the doctrine of the Trinity.) Therefore they attacked it for undermining the biblical sense of the Son’s obedient mission. The intellectuals among the group (chiefly Eusebius of Nicomedia) also attacked homoousios for its crassness—it attributes “substance” (or material stuff) to God, who is beyond all materiality. Moreover the term is unsuitable because it is “not found in the Holy Scriptures,” and indeed this did disturb many of the bishops present for the occasion.

The great majority of bishops still endorsed the idea, however, and so with Constantine pressing for a consensus vote, the word entered into the creed they published. It was not that the bishops at Nicaea were themselves simply looking for a convenient consensus in the synod’s vote. Many synods had been held before this extraordinarily large one at Nicaea, and ancient bishops predominantly worked on the premise that decisions of the church’s leadership required unanimity. Their task was to proclaim the ancient Christian faith against all attacks, and this was not something they felt they had to seek out or worry over—they simply had to state among themselves a common and clear heritage, one that could be proclaimed by universal acclamation. They believed that they were the direct continuance of the first apostolic gathering at Jerusalem, when the Holy Spirit led all the apostles to the realization of the gospel truth.

Because of this, when a few bishops dissented and refused their vote, the remaining bishops excommunicated and deposed them, accusing them of having refused to be part of the family of faith. Among this group was Eusebius of Nicomedia. All the deposed bishops received harsh sentences from the emperor (although Eusebius was confident he could wiggle out of his disgrace, as soon he did).

The End? Not Quite

Once the main item of controversy was settled (the acceptance of Alexander’s clauses and the admittance of the word homoousios), the other items fell into place quickly. The newly amplified creed was given a set of six legal “threats” attached to it (named anathemas), which spelled out in great detail all the classic marks of Arian philosophy and threatened with excommunication any who maintained them thereafter.

The meeting then turned its attention to what most bishops had originally wanted to do anyway—set up reforms to consolidate a church in the East that had long been torn apart by oppressors and had not been able to regulate its affairs on the larger front for many years. To resolve such problems, the bishops drew up a list of laws (named canons, from the Greek word for “rule” or “normative measure”). These 20 canons have never attracted as much attention as the doctrines of Nicaea, but actually had immense importance, as they were the reference point around which all future collections of church law were modeled and collated (see pp. 18–20).

After all doctrinal and canonical work was finished, the emperor concluded the council with great festivities. Hardly was the council closed when the old party factions broke out with as much rancor as before. Even stalwart advocates of the Nicene council—men like Athanasius the Great, Eustathius of Antioch, and Ossius of Cordoba—wondered, as the fourth century progressed, whether this had been a good idea or not. Those who attended the Council of Nicaea might well have felt at first that they had achieved a lasting settlement. As we shall see, however, the controversy was far from over.

CH

By John Anthony McGuckin

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #158 in 2026]

John Anthony McGuckin is an archpriest of the Orthodox Church in the Patriarchate of Romania’s Western-European Archdiocese; professor of theology at Oxford University; and Nielsen Professor Emeritus at UTS and Columbia University New York. This article originally appeared in CH #85 and was adapted for this issue.Next articles

Which creed is which?

The “Nicene Creed” used in church hymnals and liturgies is a different creed from the one accepted at Nicaea in 325

D. H. WilliamsDo you know whom you worship?

How the Nicene Creed sharpened understanding and confession of the faith

D. H. Williams“And in one Lord Jesus Christ”

Arguments on the relationship of Father and Son

various ancient authors