Christianity converted

[Columbus landing]

ON FRIDAY MORNING October 12, 1492, Christopher Columbus’s (1451–1506) expedition made landfall in the Bahamas, and he recorded the events of that day in his journal. After observing “naked people” on the island’s shores, Columbus and a group of armed men disembarked from their ships. He immediately claimed the island for Ferdinand and Isabella, the Catholic monarchs of Spain who had sponsored his voyage.

Next his thoughts turned toward religion, and he observed that the inhabitants (the indigenous Taino people) could be “more easily converted to our Holy Faith by love than by coercion.” Columbus and his men traded glass beads and other items of small value with the Taino and attempted to communicate through signs.

Reflecting on the day’s events, Columbus came to several conclusions. He believed the Taino were “very poor people in all respects,” but would “make good servants” because they were intelligent, that “they would readily become Christians” because “it appeared to me that they have no religion,” and that he should take some captive to learn Spanish and serve as translators.

Three-part plan

In his brief journal entry, Columbus foreshadowed later Spanish intentions for the Americas. First, the Spanish would claim already-inhabited land and extract its wealth for themselves. Second, they would incorporate indigenous populations into colonial society as servants, captives, and slaves. And third, they would Christianize them, not hesitating to use coercion as they deemed necessary.

The Spanish soon began to execute this implicit plan. On Columbus’s second voyage in 1493, Spanish explorers established a colony in Hispaniola and started to conquer Caribbean islands and enslave their populations. By 1511 they had invaded Cuba; soon after they started tenuous colonies in Panama.

By the end of 1521, Hernán Cortés (1485–1547) and his men, after helping to spark an indigenous civil war, captured Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztec Empire, and renamed it Mexico City; by the mid-1530s, Francisco Pizarro and other Spanish adventurers had seized control of the civil-war ravaged Inca Empire in South America. Spanish dominion, abetted by waves of European diseases that killed about 90 percent of the indigenous population by 1650, slowly expanded after these initial victories—bringing much of the Americas, at least nominally, under Spanish control.

Even so the “easy conversion” Columbus had envisioned proved illusory. Although many indigenous peoples adapted to Spanish rule and worked as forced or free laborers on Spanish estates and in Spanish mines, indigenous cultures and religions remained resilient. Some groups and individuals simply resisted Christianization—a few dramatically and violently, others cautiously and secretly. More often, however, people adopted Christian beliefs and practices but understood them within an indigenous framework.

The Spanish monarchy embraced the evangelization of the Americas. Priests often accompanied conquistadors or were dispatched to convert the recently conquered. To recognize the monarchy’s efforts and spur evangelization, Pope Julius II granted the crown the patronato real, or royal patronage, in 1508. This gave the crown the right to nominate all bishops and priests in its American territories, effectively giving Spanish monarchs unparalleled civil authority over the American church. Initially the Spanish crown sent Franciscan, Dominican, and Augustinian friars to missionize the Americas. After the Spanish colonies were more firmly established and more Spaniards had immigrated, the crown appointed bishops to administer newly created dioceses and sent more priests as parishes multiplied.

Spanish Catholics labored in missionary fields that eventually stretched from Texas and California in the north to Chile and Argentina in the south. Many priests lived in indigenous towns and villages, learned indigenous languages, taught the catechism, performed the sacraments, and preached to their flocks. They also destroyed indigenous temples, desecrated indigenous religious images, burned indigenous codices, and harried indigenous priests and shamans, believing the devil had inspired indigenous religions.

All the while they monitored their charges and meted out punishments for religious infractions. Although a few priests denounced conversion through force, most early modern Spaniards were steeped in the history of the long Christian reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula from the Moors—only completed in January 1492— and they naturally combined coercion and faith.

Many gods, one God

Contrary to Columbus’s assessment that the “Indians” had no religion, the indigenous peoples of the Americas had well-developed, deeply rooted religious cultures. In Mexico, the Aztec built grand pyramids topped by temples dedicated to the many divinities who populated their religious cosmos. Twin temples to Huitzilopochtli, the Aztec tribal deity and war god, and Tāloc, the rain god, sat atop the main pyramid of Tenochtitlan, known as Coatepec, or Serpent Mountain. At these and other temples, Aztec priests regularly sacrificed their own blood and human captives to nourish the gods so that they would keep the universe in balance.

In the Andes Inca priests and priestesses dedicated themselves to Inti, the Inca sun god; Illapa, the god of thunder; and Pachamama, the earth-mother, among others. Besides these imperial-level deities, Andean peoples worshiped huacas, physical manifestations of divinities and spirits. Huacas could take many forms, including mountains, outcroppings of rock, stones, springs, and the mummified remains of ancestors.

Although these cultures were diverse, most shared three features distinguishing them from Judeo-Christian heritage. First, they were all polytheistic (worshiping many gods). Second, many were monistic—(balancing opposing sacred forces to achieve cosmic equilibrium). Last, they did not sharply separate the sacred and the mundane, so that aspects of the physical world, including the landscape, could be considered divine. These broadly shared religious features would complicate the Christianization of the Americas.

Corn, beans, and rain

In 1524 the first officially sanctioned missionaries, a group of 12 Franciscans, arrived in Mexico to convert the defeated Aztec. The Aztec lords and priests received the 12 ceremoniously, listened to their preaching politely, and acknowledged that the Christian God had sent the Franciscans among them and that the 12 acted as “his own eyes, ears, and mouth.” But they explained to the Franciscans that their ancestors had taught them to honor their gods and keep their rituals and sacrifices and that their gods provided them with corn, beans, and rain. They protested that “it would be a fickle, foolish thing for us to destroy the most ancient laws and customs” of their people and warned:

Watch out that we do not incur the wrath of our gods. Watch out that the common people do not rise up against us if we were to tell them that the gods they have always understood to be such are not gods at all. . . . As for our gods, we will die before giving up serving and worshiping them.

The Aztec laypeople did not resist evangelization as dramatically as the lords and priests predicted, but other indigenous groups did, openly rebelling against both Spanish political dominion and Christianity. The most public early rejection occurred in Peru in the 1560s and is known as Taki Onquoy (dancing sickness).

Participants believed the spread of Christianity had angered the huacas into leaving the mountains, stones, and streams they had previously inhabited and possessing humans as their messengers. The possessed trembled and danced in circles and demanded that Andeans resume sacrificing food to the huacas and renounce the Christian God. They proclaimed the huacas would overthrow the Christian God, kill the Spanish, and return the land to indigenous control. At least 8,000 joined the movement, but Spanish colonials eventually quashed it.

This kind of collective indigenous resistance to Spanish rule and Christianity occurred throughout the colonial period (see “Dancing sickness and ancient gods,” pp. 12–15). The Pueblo revolt, the most prominent rebellion in northern Latin America, took place in 1680 in present-day New Mexico. Organized by indigenous leader Popé (d. 1692), it linked indigenous peoples of differing ethnicities who lived in pueblos around Santa Fe. Many factors contributed to the rebellion’s outbreak, not least of which was drought; but hostility toward missionary Franciscans’ prohibition of traditional religious practices and destruction of religious artifacts also stoked resentment.

Popé proclaimed the rebellion would bring back the traditional gods to bless the participants with health and wealth. The rebels unleashed their assault in August 1680, killing many Spanish settlers and 21 of the 33 Franciscan friars in New Mexico. They held the territory for 12 years until the Spanish reconquered it.

Jaguar in exile

Most resistance was not open and violent. Rather many indigenous people preserved traditional religious practices quietly and in secret. The number who consciously rejected Christianity and furtively continued ancient rituals must have been significant in the first generation or two after conquest when first-hand knowledge of pre-Columbian religions remained common. However we only know about those individuals who came to the attention of missionaries.

For instance Martín Ocelotl “Jaguar Warrior” (1496–1537) trained as an Aztec priest before the arrival of the Spanish and apparently served as a soothsayer for Montezuma—the Aztec emperor who greeted Cortés and his men and invited them into Tenochtitlan. Ocelotl survived the conquest and was baptized in 1525, one year after the Franciscan 12 had arrived in Mexico.

After his baptism Ocelotl continued to perform traditional rituals and prayers individually and for small gatherings. (Surely others did likewise, but their practices were not always recorded.) The Aztec paid him for his services as a healer and diviner and revered him for his reported ability to transform himself into a jaguar (ocelotl). More ominously for the missionaries, Ocelotl also preached against the friars and Christianity.

In 1536 the first bishop of Mexico, Juan de Zumárraga, caught wind of Ocelotl’s activities and put him on trial, calling indigenous witnesses. Convinced of his guilt, the bishop exiled Ocelotl to Spain. But he never reached Europe; the ship carrying him went down at sea.

Somewhat later and a bit further south, the Maya people of the Yucatán suffered greatly once missionaries discovered their clandestine continuation of rites honoring traditional gods. Franciscans first began to missionize in the Yucatán in 1545, soon founding eight monasteries and baptizing countless Maya. But in 1562 missionaries in the province of Maní found evidence that baptized Maya maintained traditional sacred images and persisted in worshiping Maya divinities.

The friars questioned them, and they admitted that they still worshiped Maya gods and stated that others also participated in secret ritual practices. This information caused the Franciscans to launch an investigation, and they tortured those implicated into confessing their apostasy.

Upon hearing this news, newly elected Franciscan Provincial of the Yucatán Diego de Landa (1524–1579) intensified the inquisition and expanded it into neighboring provinces. Under his guidance the Franciscans tortured over 4,500 people, killing 157, and confiscated numerous Maya images. The Maya confessed under torture that they continued to practice human sacrifice—on a much reduced scale—behind the friars’ backs. But these reports are impossible to substantiate.

Why would the Maya so readily confess? Aware that missionaries sought to eliminate all vestiges of native images, codices, temples, and religious rites, they had practiced their ancient rituals in secret. But as polytheistic worshipers, they did not perceive a sharp distinction between old and new. Like other indigenous peoples, their religions easily accommodated new deities and added the gods of conquering states to their pantheons. They recognized the new gods’ powers and sought to harness them for their own benefit or at least to placate the gods to avoid harm.

For this reason most conquered indigenous peoples did not reject the Christian God—they simply added him to what they viewed as his divine indigenous counterparts. The fact that the Spanish had defeated them militarily testified to his might; so they deemed him worthy of worship and began to worship the Trinity and venerate the Catholic saints introduced by the missionaries—even as they rejected Christian exclusivity.

The sacred tree

After the first generation of evangelization, widespread conscious maintenance of indigenous religions declined significantly. Individuals and isolated groups continued traditional ways, but their numbers dwindled after decades of colonial rule accompanied by waves of Old World disease and years of extirpation campaigns.

By the early 1600s, most indigenous peoples in populace areas of the Spanish Americas accepted Christianity and its exclusivity and considered themselves good Catholics. Their parents and grandparents had no direct knowledge of ancient religions and temples; monasteries had stood in their towns since before they were born. They had grown up participating in Catholic sacraments and learned at least the rudiments of the faith since childhood. For them Christianity had become the given order of the world.

Despite this naturalization of Christianity, by the mid-seventeenth century, indigenous worshipers practiced forms of Catholicism that would have appeared odd to Europeans. Most indigenous peoples over time submitted to the Christian God’s demand for exclusive worship. But they thought about and honored him and his saints in indigenous ways.

A striking example of this is a magnificent stone cross carved by an indigenous artisan for the courtyard of the monastery of San Agustín in Acolman, Mexico. It clearly represents the crucifixion, and the artisan carved symbols of the Passion (nails, a rooster, a whip, and a ladder) into its shaft. At its base the Virgin mourns Christ’s death. But unlike European crucifixes, the Acolman cross depicts Jesus’s head emerging from the cross itself; floral designs cover the crossbar and buds sprout from its ends, as in the indigenous sacred World Tree.

Sweeping up for the Trinity

Similarly an unsigned gift of land written in Nahuatl in 1621 in Coyoacan, near Mexico City, notes that an unnamed (probably female) indigenous person had been “sweeping up [in her house] for [the image of] the Most Holy Trinity,” an image that was to be moved to the school housed in the town’s Dominican monastery. She donated her house to honor the Trinity and directed the school children to continue “to sweep for” the image.

The donation revealed this woman’s long-standing devotion to the Christian God; but the demonstration of devotion by sweeping displayed something more. Aztec priests and priestesses had regularly swept their gods’ temples for cleanliness and ritual purification; Aztec women also swept homes for the same reason. This unnamed woman, 100 years after the conquest of Tenochtitlan, served the Christian God through traditional Aztec practices.

In a final example, The Virgin Mary and the Rich Mountain of Potosí, painted by an anonymous indigenous artist in Bolivia around 1740, depicts the Trinity crowning Mary the queen of heaven in front of the king of Spain, the pope, and others. All this, except for the indigenous figures, would not have been out of place in a European painting. But the Virgin is shown as the Mountain of Potosí, the world’s richest source of silver for most of the seventeenth century. In the ancient Andes, the mountain had been identified with Pachamama, the Inca earth-mother goddess. It is likely that the artist revealed here a persistent understanding that the landscape manifested sacred power.

In the end indigenous peoples of the Americas largely accepted Christianity after some early resistance; within a few generations of Spanish conquest, they also acknowledged Christianity’s monotheistic exclusivity, a transition eased by early modern Catholicism’s penchant for venerating saints. But although they readily adopted Christian ideas, they understood them within local frameworks. By and large they were good Christians by the early seventeenth century. But they were Latin American, not European, ones. CH

By Brian Larkin

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #130 in 2019]

Brian Larkin is professor of history at the College of Saint Benedict/St. John’s University in Collegeville, Minnesota, and author of The Very Nature of God: Baroque Catholicism and Religious Reform in Bourbon Mexico City.Next articles

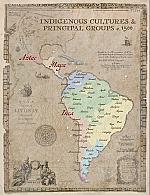

Map: Indigenous cultures & principal groups, c. 1500

Map of indiginous groups when Europeans arrived in the new world

the editors