Dancing sickness, ancient gods

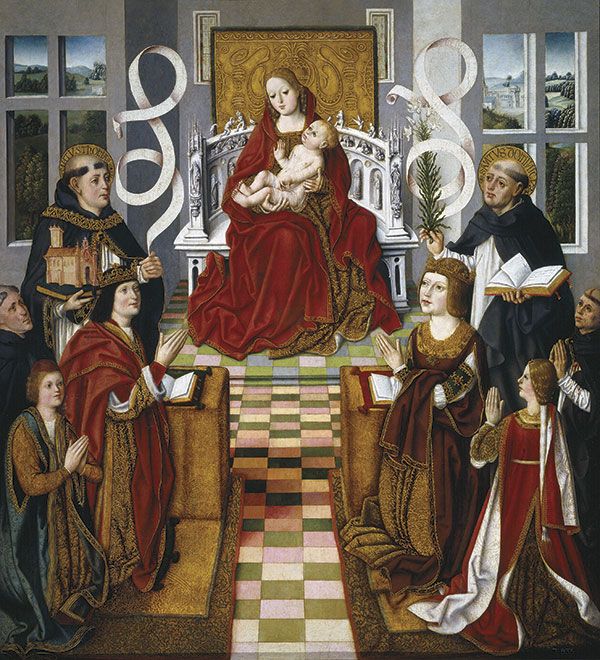

[The Spanish monarchs worship with their children/ Wikimedia]

MODERN CHRISTIANS still tend to think of first-contact missions in tidy, complete, and rosy terms. But this vision hides a more complicated reality. As carriers of a new culture—not just a new religion—the first missionaries to the Americas disrupted native peoples’ ways of marking time, living together, naming themselves and the world around them, and much more.

This was true for both indigenous Latin American groups and enslaved Africans. And to the dismay of colonial authorities, African and indigenous traditions gained acceptance among Spanish immigrants and others over time. Indigenous peoples tended to resist missionary demands to worship the Christian God alone, finding ways to combine this new faith with their own ancestral beliefs and rituals, weaving colorful—and sometimes clashing—threads into the colonial religious tapestry.

Conquistadors impose a new God

From the early days of conquest, Spanish colonizers saw Christian evangelization as the most important reason to be there. No clergy accompanied Columbus on his first voyage to the Caribbean, but he was convinced that the conversion of natives to Christianity would be swift and thorough. A misguided but similar optimism suffused other early expeditions.

Hernán Cortés brought two priests in the early 1500s, but it was not until Franciscans arrived in 1523–1524 that evangelization hit its stride. Convinced the end of the world was coming, the Franciscans sought to hasten the Second Coming by converting the natives. Although other conquistadors rejected this apocalyptic vision, all saw themselves as God’s chosen instruments to expand Christianity at whatever cost.

In Peru Dominicans organized the first missionary expedition accompanying Francisco Pizarro González (c. 1471–1541) in 1524. Mercedarian and Augustinian religious orders later joined the tumultuous first decades of colonization in the Andes. In Brazil Jesuit Manuel de Nóbrega (1517–1570) led the first missionary efforts in the area of Bahia from 1549 on; until expulsion from Brazil in 1759 and the Spanish colonies in 1767, Jesuits played a decisive role in expanding Christianity into the remotest regions.

Friars in charge

Resistance from native peoples was only the first of a bevy of conflicts. In the early decades of evangelization, the Spanish priests’ own ranks were divided. Heated disputes broke out between secular clergy (diocesan priests ministering to everyday people in the secula—the hurly-burly of “this age” ) and regular clergy (members of orders following a regula, or rule).

European ecclesiastical and political leaders muddied the waters further. With the blessing of Pope Adrian VI’s edict Omnimoda (1522), King Charles V granted regular clergy the ability to perform all sacraments in the New World, a task normally restricted to secular clergy in Europe. Friars were elevated to bishop status because of the lack of qualified secular clergy. Placed under the direct authority of the pope, these mendicant friars operated with relative autonomy.

In 1574, however, King Philip II issued a series of decrees, Ordenanza del Patronazgo, that shifted crown support to the secular clergy and ordered the replacement of missionaries by diocesan priests. As seculars increased in number in the late sixteenth century, they gained control of the bishoprics and fought the mendicants over diocesan boundaries, access to indigenous tithes, and control of other resources.

As so often happens, power inflamed the conflicts. Regular clergy competed with the encomenderos, Spaniards allowed to exact tribute and labor from the Indians provided they cared for them materially and spiritually in exchange. The ideal was to accelerate conversion to Christianity and European culture while protecting the natives; but in practice it turned into brutal exploitation of unpaid Indian labor.

In “Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies“ (1542), Bartolomé de Las Casas presented the king with horrifying details of Spanish cruelty and urged him to abolish the encomienda. His denunciations apparently led King Charles V to issue the New Laws (1542), which among other things prohibited encomienda inheritance. As expected this proved extremely unpopular. In Peru strong resistance triggered a bloody civil war.

Although the Franciscans did not oppose the encomienda system, they denounced Spanish violence. Seeing the natives as children, they were convinced that only segregation could save them from moral corruption and physical extinction by the Spanish. Partly responding to these concerns, the crown enacted a system of physical and racial separation that kept Indians and Spaniards in different administrative and fiscal orders known as repúblicas (commonwealths).

But it was already too late to separate in any lasting way. The Spanish continued their demands for native labor; the two groups were already intermarrying; and natives had a hard time keeping Spaniards out of their towns. In Brazil bands of slave-raiders attacked Jesuit missions with distressing regularity, and local landowners and government officials complained about Jesuit monopoly over Indians. By the 1750s relations between the Jesuits and the Portuguese soured, resulting in their expulsion from the empire.

In spite of missionary enthusiasm, Indian conversion to Christianity proved short-lived at best, with years of numerous baptisms, casual instruction in dogma, and perfunctory supervision. As the euphoria of the early years waned, disappointed missionaries resorted to coercion and corporal punishment. Acting as inquisitors they brutally chastised Indians in Acolhuacan (1522), Tlaxcala (1527), and other regions in Oaxaca and Yucatán. In 1539 Bishop Juan de Zumárraga famously sentenced Don Carlos Ometochtzin, a noble from Texcoco, to be burned at the stake on charges of heresy.

Indigenous acquiescence remained elusive, however. In 1562 Zumárraga’s fellow Franciscan bishop, Diego de Landa, conducted a violent three-month campaign against idolatry in Mani, Yucatán, overseeing the savage torture of more than 4,000 Maya. Hundreds died in the interrogations, and many others killed themselves in despair.

About the same time, a pan-Andean rebellion known as Taqui Onqoy (dancing sickness) announced the imminent defeat of the Christian god by the powerful huacas (see “Did you know?,” inside front cover) and urged natives to reject collaboration with the colonizers.

A golden age

In 1680 a medicine man named Popé told Pueblo Indians that the Spanish were to blame for the horrible drought, famine, pestilence, and deaths they had endured for years; only killing the colonizers would make the katsina (ancient gods) return and bring a golden age of prosperity. On August 10, 1680, an army of 8,000 Pueblo Indian warriors razed churches and pillaged Spanish settlements, killing more than 400 within hours. Not until 1692 did the Spanish finally rout the rebels.

In 1712 a pan-Maya coalition known as the Cancuc Rebellion inaugurated a new era of indigenous revolts. In contrast to its predecessors, it did not aim at revitalizing ancient religion but at defying Spanish control of Catholicism. It occurred during the era of the Bourbon Reforms, a period of crucial changes for Iberian America that tried to nationalize colonial exploitation, strengthen colonial links to the mother countries, improve tax collection, and revamp bureaucracy.

The reforms also discouraged popular expressions of piety and devotion as unnecessary and extravagant. When a 13-year-old Indian, María de la Candelaria, claimed to have seen the Virgin Mary in the outskirts of Cancuc, the local priest dismissed the apparition; but María’s father and others built a chapel on the spot.

Followers of the cult refused tribute to Spain and rejected the authority of king and bishop. A rebel confederation of 32 Tzotzil, Tzeltal, and Chol villages attacked Chilan, Ocosingo, and other towns. Internal differences and growing numbers of Spanish attacks weakened the movement, and it was finally crushed in November 1712.

The rebellion of Túpac Amaru II in Peru and Bolivia in the 1780s represented the climax of an impressive number of uprisings. Combining utopian Christianity with a cyclical worldview of renewal and destruction (pachatui) taken from traditional practices, Túpac Amaru II imagined a golden era of justice and harmony free of Spaniards, Creoles, and their allies and ushering in the return of the Inca king (the Inkarri). He commanded an army of 40,000 Indians, mestizos, black slaves, and even whites; but the Spanish defeated them within six months. Túpac Amaru II and his family were brutally executed in 1781, but his relatives continued rebelling for two more years. Rumors of the return of the Inkarri persisted through the colonial era.

Strike off the chains!

Colonial authorities frequently claimed that Christianizing African slaves would make them more docile and content, but Christian slaves still resisted, rebelled, and ran away. They even used Christian institutions such as confraternities (see p. 20) to organize uprisings.

In 1611 for example, an angry crowd of 1,500 belonging to the black confraternity of Nuestra Señora in Mexico City filed past governmental and Inquisition palaces carrying a female slave who had been flogged to death, then threw stones at the home of her master, Luis Moreno de Monroy. Later they selected an Angolan couple, Pablo and María, as king and queen and planned an ambitious rebellion for Holy Thursday of 1612 with the financial support of several black confraternities.

Portuguese merchants, learning of these plans by accident, reported them to the colony’s High Court, which ordered leaders arrested and tortured. Seven women and twenty-eight men were publicly hanged in the main square. Authorities quartered six of their bodies and scattered them on the roads, leaving their heads on display at the gallows.

Large-scale slave rebellions often created maroon communities known as quilombos (Portuguese), or palenques, manieles, and cumbes (Spanish). Consisting of runaway slaves, they were strategically located in mountains, dense forests, and other inaccessible areas.

Maroons usually re-created African religious traditions but also incorporated elements of Christian worship. At Yanga in Veracruz, Mexico, for example, they built a small church with a bell tower, adorned its altar with lighted candles, and planted arrows on the ground in front. Portuguese troops found several churches with statues and saints in the abandoned villages of Palmares in Brazil.

Ultimately although Catholic authorities frequently reported on eager conversions, these conversions often represented a desire for the religious power of the colonizers—not a decision to abandon old rituals and beliefs. The colonized tended to endow Christian saints and the Virgin Mary with African and indigenous attributes (see “Mother of Mexico,” p. 21). Authorities objected to this syncretism and deemed diabolic and superstitious the widespread use of divination, healing, and witchcraft; but the conjurers and healers paved the way for forms of folk Catholicism with strong African and indigenous content—a process neither tidy nor complete. CH

By Javier Villa-Flores

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #130 in 2019]

Javier Villa-Flores is associate professor of religion at Emory University and author or editor of several books on Latin American social history including Dangerous Speech and Emotions and Daily Life in Colonial Mexico.Next articles

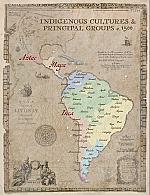

Map: Indigenous cultures & principal groups, c. 1500

Map of indiginous groups when Europeans arrived in the new world

the editors