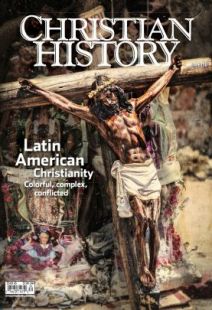

Making faith their own

[Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Peru / Wikimedia]

IN 2010 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC published an article about Nuestra Señora de Santa Muerte, Our Lady of Holy Death. A personification of death itself, this Mexican “folk saint” is portrayed as a female grim reaper who offers her followers protection from earthly trouble and an easy transition to the next world. Her image is found in street-shrines and jail cells, and her popularity is seen as a response to the rise of drug cartels and their associated culture of violence.

The Catholic Church has condemned the cult of Santa Muerte; even so the number of those who venerate her grows. Stories of folk saints like Santa Muerte and the possibly mythical “generous bandit” Jesús Malverde dramatically highlight a number of complex threads woven through Christian worship and devotion in Latin America.

Compel them to come in

Geographically Latin America is expansive, encompassing more than 7.4 million square miles, and it is home to about 640 million people today. When Europeans arrived a diversity of peoples, cultures, and religions already filled the land (see “Christianity converted,” pp. 6–11). Europeans also brought large numbers of enslaved Africans who added their own unique cultural and religious traditions to the mix—such as orixás, guardian spirits in the Yoruba religion who became associated with Catholic saints.

The Europeans, it is said, conquered with the sword and the cross; conquistadors arrived with priests, monks, and friars in tow. Many orders worked to bring the gospel to Latin America, including Mercedarians, Franciscans, Augustinians, Dominicans, and Jesuits. As colonies were established, Catholic ecclesiastical structures were put in place, and the church set out to convert the crown’s new subjects to the Catholic faith.

This evangelism often took place under the encomienda, which granted colonists land and allowed them to use the people inhabiting that land as forced labor. A priest was assigned to care for these people—teaching them the faith, baptizing, and administering the sacraments.

The priest Bartolomé de las Casas, a part of this system, came to care deeply for the laborers under his care. Eventually he gave up his encomienda and urged others to do the same. Some itinerant priests charged with the care of those outside the colonies traveled to remote villages, suffering great hardship to serve those communities by offering pastoral care, preaching, and even defending them against colonial abuses. De las Casas himself contributed through his lobbying to the legal abolishment of the encomienda system.

Thousands upon thousands of baptisms

Reports from the period describe mass conversions of thousands of Maya, Inca, and Aztec people at the point of a sword, but the public denunciation of one’s religious traditions did not necessarily reflect personal heart-felt conviction or genuine acceptance of the Christian God. In some instances the success of the Spanish in battle was a convincing display to indigenous people that the old gods had been defeated. But old beliefs and traditions lived on.

Eager European missionaries had to translate their message for a new audience and into new languages. In 1570, for example, the Aztec language of Nahuatl became the official language of New Spain, in part for use by the church. For the next century, the gospel would be presented in this native tongue, until the Spanish crown changed its mind in 1696 and made Spanish the official language of the entire empire.

Missionaries couched their teaching in the metaphors and imagery of the people they were trying to reach. The cross might be described and pictured with Tree of Life imagery, for example (see “Christianity converted,” pp. 6–11), or its shape pointed out in the flight of a condor, a bird unknown in Europe.

Language barriers and the mistaken belief that indigenous peoples were not as intelligent as Europeans led many priests to depend on “holy objects” such as rosaries, candles, and pictures. The ancient indigenous tradition of the huacas (see “Did you know?,” inside front cover) and the long-standing importance of the saints to lay Catholic immigrants combined to create something new—a calendar of saints replacing, yet not quite replacing, the sacred objects and gods of pre-Columbian religion.

As a result a constant tension developed between the orthodox doctrine of the priests (also generally the social and cultural elite, as the priesthood was reserved for “pure-blooded” Europeans) and the visions and devotional practices of lay Latin American Catholics, such as Mexican peasant Juan Diego who claimed in 1531 to have been visited by the Virgin Mary (see “Mother of Mexico,” p. 21). Such visions and images became increasingly associated with outcasts, the poor, and those of “mixed blood.”

For example in Cuba a slave boy and two indigenous men discovered a statue of the Virgin while caught in a storm, resulting in the story of the Virgin of Caridad del Cobre; she became the patron saint of Cuba. In Bolivia indigenous sculptor Francisco Tito Yupanqui (1550–1616) fashioned a statue of the Virgin as Our Lady of Candles. Yupanqui, who claimed descent from Inca emperor Huayna Capac, said the Virgin visited him in a dream and asked him to make the image. When the parish priest asked Yupanqui to give the statue a European look, the sculptor argued (successfully) that it needed to look Bolivian.

Failed Protestants, exiled Jesuits

Protestant colonies were also established, but they died out quickly and made little impact on popular devotion. A short-lived French Huguenot colony, for example, was established in Brazil in 1555. Decades later in 1630, a Dutch colony began in Brazil but lasted only 24 years. Yet changes—small but dramatic—were in the air. In 1767 a religious struggle between the Jesuit order and Charles III led him to expel them and confiscate their property. (The order would be suppressed in Europe as well in 1773 and would reorganize in the nineteenth century.)

Much Jesuit property went to other religious orders, increasing their holdings and creating a new target for the king’s authority. Some of those expelled were from the criollo casta and had to leave their birthplaces. Towns lost priests, and parishes lost confessors in the resulting leadership vacuum. The Jesuits had also been among the most sympathetic to miraculous stories and events.

A little over a hundred years later, the rejection of European political rule in the early 1800s created yet another crisis. Many local priests sympathized with revolutionary ideas, while church leadership often sided with the foreign monarchies of Portugal and Spain.

When new governments were established, the close relationship the church had maintained with the Iberian crowns came into question. Property was seized and sold. In some places tithes were abolished, and in others clergy lost certain rights and privileges. In Guatemala the Jesuits—back since 1801—were expelled again in the 1870s. The availability of worship, schools, and other services from Catholics or Protestants shifted with the political climate.

Protestantism took permanent hold in the early nineteenth century (see “Strangers in a strange land,” pp. 29–33); it too would become thoroughly Latinized. James “Diego” Thomson, who arrived in Argentina in 1818, visited nearly every country in Latin America and advocated for translating the Bible into indigenous languages. Other Bible societies saw Thomson’s success and followed his example. It is estimated that 80 years later, two million Bibles had been distributed throughout Latin America.

Other missionary groups were also at work. Methodists established congregations in Argentina and Chile. African Americans seeking to escape racist policies in the United States immigrated to Haiti and the Dominican Republic, bringing the African Methodist Episcopal Church with them.

“The crazy father”

While some Protestant missionaries focused on converting indigenous groups practicing non-Christian traditions, others focused explicitly on converting Catholics. Ex-priests and ex-friars occasionally became missionaries. José Manouel da Conceiçao (1822–1873), called by his former colleagues “the crazy father” and “the Protestant father,” hoped to spark a renewal within Catholicism from his new status as a pastor in the Presbyterian Church of Brazil.

The twentieth century saw even more immigration along with more directed missionary efforts. Mennonites, for instance, fled south to escape required Canadian military service. They ended up ministering to those caught in war between Bolivia and Paraguay; their nonviolent witness brought them over 8,000 new converts, although as late as the twenty-first century, German and indigenous language speakers still worship separately.

In the early part of the twentieth century, Pentecostalism—a charismatic expression of the faith that highlights the gifts of the Holy Spirit, in particular glossolalia (speaking in tongues)—arose in several places. In the United States, Pentecostal revival sparked at the Azusa Street Mission in Los Angeles in 1906. Three years later at a large Methodist church in the city of Valparaiso, Chile, a Pentecostal revival began during a regular meeting. The pastor of the church was Willis Hoover, an American Methodist Episcopal missionary and founder of the congregation (see “Charity toward all,” pp. 44–47). Soon people began speaking in tongues in other churches across Chile.

Pentecostal revival meetings also arose in Brazil and Mexico. In Mexico the movement led to, among other things, the creation of the Iglesia Apostólica de la Fe en Cristo Jesús (Apostolic Church of Faith in Jesus Christ) through the work of Romana Carbajal. From humble beginnings the denomination grew to over a million members in less than a hundred years.

Pentecostal worship in Latin America, as in the United States, features not only tongue-speaking but prophecy, miraculous healings, extensive prayer, testimony (testimonios), and other ecstatic manifestations; there is a tendency sometimes toward preaching the “prosperity gospel,” which maintains that God will bless his followers with material wealth. Some groups, including those stemming from Carbajal’s work, baptize in the name of Jesus only. Nearly all groups make heavy use of lay preachers and missionaries who raise their own support.

In the end the story of Christian devotion in Latin America is less about the straight line of Christian faith piercing old traditions and more about how faith in both orthodox and unorthodox ways becomes the faith of the people who hold it. CH

By Matt Forster

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #130 in 2019]

Matt Forster is a freelance writer living in Houston.Next articles

Christian History timeline: Latin American Christianity

Christianity in Latin America has a rich and complicated, history encompassing many different countries, traditions, and political situations. This timeline offers a brief introduction to both church (in bold) and state (in italic).

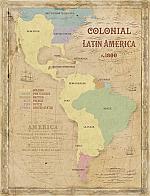

the editorsCentral and South America 20th century map

Map of Central and South America in the twentieth century

the editorsStrangers in a strange land

Protestantism and power in nineteenth-century Latin America

Joel Morales Cruz