Strangers in a strange land

[Young Patagonians / South American Missionary Magazine]

IN 1888 FRANCISCO PENZOTTI (1851–1925), a Uruguayan Methodist, began holding Protestant worship services in Peru. Word got around; in 1890 he was hauled off to jail for proselytizing, having violated Peru’s colonial restrictions on publicly exercising non-Catholic religion. As Panzotti starved in a dungeon, Peruvian elites heard of his case. The New York Herald took up his plight, and the whole world learned of Peru’s policies just as elites were seeking to encourage foreign investment and trade. By the time the case reached Peru’s Supreme Court, the climate was ripe for change. Peruvian Protestants and the Liberal political party’s leaders regarded Penzotti’s acquittal as a victory for religious freedom.

Continued struggle

Protestantism in nineteenth-century Latin America involved competing and converging national, political, religious, and economic interests on the part of state leaders, missionaries, and ordinary people. Two dominant political factions emerged following nineteenth-century wars for independence from European control: Conservatives, who sought to preserve colonial structures as much as possible; and Liberals, who worked to bring the emerging nation-states into the modern world.

Among other things they contended over religion. Conservatives favored maintaining the power of the Catholic Church, which paralleled their own power. Liberals challenged the traditional privileges of the church and took over maintaining its registry of births, marriages, and deaths and running schools and charities. Because the church remained one of the wealthiest landowners even after independence, both groups sought to exploit or control it and access its resources to support struggling governments or war efforts.

Early constitutions of the new republics upheld Catholicism as the state religion and sole legal religious institution. Conservatives thought the church created and preserved national unity and stability and bound people in a common worldview and morality—especially important in countries made up of people of European, indigenous, African, and mixed descents, and ranging from very wealthy to very poor.

Liberals did not aim to abolish the church, but they did want to limit its power for the good of the nation. They thought the popular religion of the masses and elaborate Catholic rituals caused Latin American stagnation and believed Protestantism contributed to the commercial success of the United States and Great Britain. Toleration seemed necessary to establish trade and diplomatic relationships with Protestant countries. As a compromise, religious freedom when granted was limited to foreigners and often stipulated that Protestant worship remain inoffensive to Catholics.

Take up and read

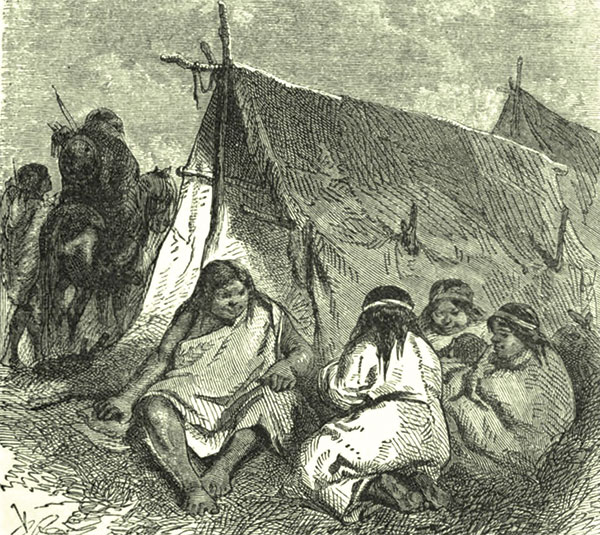

The first permanent Protestant immigrants to Latin America were British settlers taking advantage of an 1810 treaty between the United Kingdom and Portugal. Chaplains—Anglican, Methodist, and Lutheran—arrived at major ports and urban centers to serve expatriates. Initially they did not proselytize Catholics, but extended ministries to native populations who had never encountered Christianity. For example Anglican layman and British Navy officer Allen Gardiner (1794–1851) evangelized in the Bolivian Altiplano and later dedicated his life to spreading Christianity in Tierra del Fuego, founding the Patagonian Missionary Society in 1844.

Bible colporteurs (peddlers) also began to establish Bible societies and spread copies of the Scriptures. The most famous and well traveled was James “Diego” Thomson (1788–1854). The Scots Baptist trekked from Argentina to Mexico to the Caribbean, often invited by political leaders who wanted to increase literacy through the Lancasterian system (a teaching method using the Bible as a text). Colporteurs encountered mixed responses. Many Catholic clergy opposed their efforts, arguing that the Scriptures they distributed lacked the explanatory notes to prevent the faithful from falling into error (i.e., Protestantism).

Early on a translation from the Latin Vulgate was used, but eventually Bible societies moved to the Reina-Valera, translated from the original languages by Protestant converts in sixteenth-century Spain. Sometimes the Apocrypha (considered canonical by Catholics) was omitted, adding to the suspicion that Bible societies were Protestant infiltrators. However some, including clergy, welcomed and aided the opportunity to disperse the Scriptures to the people.

Among them were Mexican statesman and priest José María Luis Mora (1794–1850) and Colombian bishop Juan Fernández de Sotomayor (1777–1849). They represented a reformist strand of clergy who sympathized with Liberal goals, often breaking ranks with their superiors on matters related to church and state, education, or the role of the church in society.

Missions and modernity

In 1823 the United States’ declaration of the Monroe Doctrine essentially warned off European powers from colonial aspirations. Amid the United States’ increasing presence in the hemisphere, Protestant missionaries began to take a greater role in evangelizing the region.

The revivals of the Second Great Awakening (1795–1835) had energized US Protestantism with an emotional and optimistic faith expressed in grassroots movements throughout the country’s western frontier. Heir to Reformation theological debates and worried about increasing numbers of Catholic immigrants arriving on US shores, US Protestants were also stridently anti-Catholic and thought Latin Americans needed to be rescued from superstition. Missionaries brought with them an emphasis upon personal Bible study, justification by faith, iconoclasm, and the individual’s unmediated relationship with God.

As agents of their culture, they freely mixed sociopolitical assumptions with their religious convictions—just as surely as Spanish friars had done centuries earlier. Evangelization also meant “Americanization”—and “America” meant the United States. “Freedom” translated into the socioeconomic sphere as individualism, the “Protestant work ethic,” and capitalism; in politics, “freedom” meant democracy and republicanism. Protestant mission churches generally benefited from the Liberal governments in Latin America that advocated for religious freedom, the disestablishment of the Catholic Church, public education, and increased economic ties with the United States.

This evangelistic faith found motivating energy in Manifest Destiny, the popular nineteenth-century attitude conceiving of the United States as divinely destined to expand throughout North America by virtue of the faith, morality, and justice of the American people and their institutions. More a general mind-set than policies, Manifest Destiny was used to justify the takeover of Native American lands and the Mexican-American War (1846–1848). This war swallowed over half the territory of Mexico, making roughly 100,000 Mexicans into US citizens overnight.

Evangelists followed the expanding United States westward, but only after the Civil War in the 1860s did missionaries move southward in greater numbers, as well as overseas to Africa and Asia. As a newly invigorated and industrialized United States flexed its economic and military muscles, it made natural partners of Protestant denominations seeking new converts. Post–Civil War prosperity, industry, and advances in transportation and communication greatly aided this effort.

When Spain lost Puerto Rico and control of Cuba to the United States in the Spanish-American War in 1898, major Protestant denominations divided up the islands between themselves to establish churches and “save” people from Roman Catholicism. These missionaries generally began working among the poor and laborers, but soon moved on to the emerging middle classes—who tended to be more critical of Roman Catholic clericalism and more receptive to republican values.

A ready soil

By midcentury Mexican president Benito Juárez (1806–1872) was proposing the anticlerical Reform Laws of 1855–1860. Surprisingly, progressive Catholic clergy supported such laws. In some areas Protestant missionaries worked among these Catholic reformist clergy and with religious groups such as Mexico City’s Iglesia de Jesús (Church of Jesus) and Puerto Rico’s Bíblicos. The Iglesia de Jesús was organized in the 1850s by progressive Catholic clergy in Mexico City who supported the Reform Laws. Preaching a Christocentric message and rejecting clerical celibacy and papal authority, they eventually sought support from the Episcopal Church and in 1906 joined it.

In Aguadilla, Puerto Rico, the Bíblicos consisted of a loose arrangement of clandestine groups meeting to study the Bible. They were led by Antonio Badillo Hernández (d. 1889), who converted to evangelicalism after attending religion classes held by a Protestant merchant. Presbyterian missionaries arriving in the region after 1898 encountered these “Bible people,” who would form the nucleus of the Presbyterian effort in western Puerto Rico.

The rise of Protestantism was also connected to the rise of free-thought and radical societies. These societies formed in Mexico, Chile, Colombia, and Brazil in the 1850s. Their members tended to be miners, textile workers, and railway laborers; those in urban service industries such as clerks, bankers, and teachers; coffee producers of Colombia and São Paulo; and former soldiers and artisans of Mexico.

Neither the established middle class nor rural peasants, these groups were part of the burgeoning industrialization of cities and suburbs and keenly felt economic uncertainties. Agitating for liberal and democratic reforms and sometimes associating with Freemasons, some also expressed anti-oligarchical, anticlerical, anti-Catholic, or dissident religious opinions and activities.

As with the Iglesia de Jesús, which supported the Liberal 1857 Constitution and a vision of a reformed Christianity, these societies sought to create a non-Catholic religious alternative. When Protestant evangelists arrived, they built upon the efforts of these groups, eventually integrating them into missions. Thus Protestantism did not necessarily represent an invasive, alien presence, but rather the evolution of a process already in motion—joining economic and religious demands of reformist clerics, religious liberals, and an anticonservative emerging middle class.

US Protestants also took advantage of aggressive Liberal regimes throughout Central and South America in the latter nineteenth century to establish missions, charities, schools, clinics, seminaries, and other resources. At this stage though, the US missionary enterprise tended toward paternalism and sometimes outright prejudice. Despite the development of native leaders, North American missionaries and their denominations maintained control and would do so until the mid-twentieth century.

Expatriates find homes

Throughout the nineteenth century, Liberal governments encouraged European immigration to stimulate national economies and promote agricultural development; immigrants were guaranteed religious freedom. In his Essay on Religious Tolerance (1831), Ecuadorian Vicente Rocafuerte (1783–1847) argued:

The English, Swiss, German, and Dutch take with them an admirable spirit of order, of cleanliness, and of economy wherever fortune may take them that is worthy of imitation. . . . [This] exercises a benign influence upon the morality of the people, and one should not neglect the means of promoting it.

For example by midcentury British subjects had established Anglican churches in Argentina, Venezuela, Chile, Uruguay, Costa Rica, and Peru. German Mennonites arrived in Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay, while Russian Mennonites went to northern Mexico. Italian Waldensians found new homes in the Southern Cone. After the Civil War, African Americans, fleeing rampant racism, settled in Haiti and the Dominican Republic and established Methodism, while disaffected Confederates found homes in Brazil.

These communities tended to be isolated, forming their own churches and hiring pastors from abroad. Services were held in the mother tongue, and little evangelistic work was conducted outside the community. Only later did second and third generations identify more with the New World than the Old.

Clearly, emergent Latin American nations and new immigrants aided one another’s goals. Immigration helped these countries expand and settle the hinterlands, though tragically at the expense of the native peoples living there. At the same time, the republics served as a haven for Protestants fleeing persecution or hardship. Today Latin America still draws people in search of opportunity. Denominations once “strangers in a strange land” now meet the spiritual and material needs of communities as different as Hungarian expatriates in Brazil and Chile, and Korean Presbyterian expatriates in Chile, Argentina, Costa Rica, Paraguay, and Bolivia. CH

By Joel Morales Cruz

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #130 in 2019]

Joel Morales Cruz is adjunct professor of theology at the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago and author of The Mexican Reformation and The Histories of the Latin American Church.Next articles

“¡Llegaron los pentecostales!”

How Pentecostalism spread in Latin America and the Caribbean

Carlos F. Cardoza-OrlandiThe delicate balance of church and state in Latin America

The role of religion in Latin America remains strong, and religious voices on all sides can be heard amid current political debates.

Joel Morales Cruz