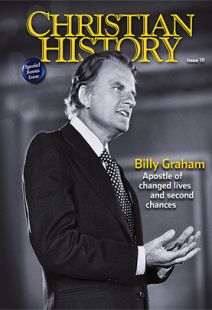

Confessor-in-chief

IN JULY 1950 31–year-old Billy Graham and three associates met with President Harry Truman. Unschooled in presidential protocol, they offended Truman by spilling the contents of their conversation to a waiting press. They then agreed to a much-photographed prayer session on the White House lawn.

As Graham’s fame spread and Democratic leaders noted his influence, Truman persistently refused further contact. He referred to Graham as “one of those counterfeits. He claims he’s a friend of all Presidents, but he was never a friend of mine when I was President.” Only much later did the two men find a modicum of reconciliation.

No one could have predicted that this first disastrous encounter with a president would establish an unparalleled legacy. Billy Graham stood in the glare of public scrutiny with US presidents and other heads of state more than any other Christian leader. Their friendships gave him unprecedented opportunity for spiritual influence that also came with great risk. It is easy to cross the line between pastoral presence and political partisanship, and several times during his storied life, Billy Graham had to redraw that line.

Graham met Dwight Eisenhower not long before Ike became the Republican nominee in 1952, but it took some special effort. A mutual friend encouraged their meeting and suggested that Graham give Eisenhower advice about how to “contribute a religious note” to his campaign speeches. The relationship soon took off, giving Graham opportunity for pastoral conversations.

Graham’s interactions with Eisenhower foreshadowed a regular pattern. Most conversations revolved around personal spiritual concerns and prayer, but in critical moments, a president would ask Graham’s perspective. When Arkansas governor Orval Faubas defied a federal order for African American students to integrate Little Rock High School, Eisenhower sought Graham’s advice about sending federal troops. “Mr. President,” he responded, “I think that is the only thing you can do.”

As Eisenhower’s trust in Graham deepened, he opened the door for personal concerns. After his first heart attack, he called Graham for pastoral conversation. He asked about heaven and admitted his lack of assurance. In 1968 he sought Graham’s help to reconcile with Richard Nixon.

This pattern of pastoral care with occasional forays into strategic matters became a temptation too great for Graham to resist. By the time Nixon made his first run for the presidency, he and Graham were fast friends, provoking Graham’s first serious temptation to political partisanship. John Kennedy’s Catholicism complicated the 1960 campaign. Other Protestant leaders like Norman Vincent Peale had made openly anti-Catholic statements in support of Nixon. Graham was by then a personal friend of Cardinal Francis Spellman and did not want to get caught in that controversy. Henry Luce, Time’s editor-in-chief, asked him to write a testimonial on behalf of Nixon. He did, then regretted it and asked Luce not to use it, narrowly avoiding a serious breach of his nonpartisanship rule.

When Kennedy defeated Nixon, Graham took it as God’s sovereign guidance that religious differences should not cause political divisions. Kennedy’s father, Joe, recognized the need for a good relationship with the Protestant evangelist and encouraged the president’s staff to arrange a meeting. When the day came, Kennedy had questions about the second coming of Christ, admitting it was a doctrine his church did not emphasize. He and Graham agreed to have a follow-up conversation that was fated never to happen.

The sleepless president

In the wake of Kennedy’s assassination, Billy Graham and Lyndon Johnson forged a lasting friendship. Had Graham succumbed, however, to the temptation to run for president, the friendship might never have developed. In 1964 the prospect of a Graham candidacy had a brief moment of life. Texas oil baron H. L. Hunt offered Graham $6 million to run. It was a real temptation, but he quickly resisted it.

A telegram of pastoral support from Graham to Johnson shortly after Johnson took office prompted an invitation to the White House. On more than 20 occasions, Graham, often accompanied by Ruth, was a guest. He also made numerous visits to the Johnson ranch in Texas. They often had spiritual conversations and prayer, occasionally in the middle of the night when the sleepless president wanted company and counsel. Johnson struggled with doubts about his salvation. On one of many car rides around the ranch, he parked the car and asked Graham to share the gospel with him once again.

Johnson also engaged Graham in social matters. In 1965 he asked him to go to Selma, Alabama, to help calm a desperately tense situation along with the placement of troops to protect the freedom marchers. Graham went.

After leaving office Johnson voiced the significance of Graham’s support: “No one will ever know how you helped to lighten my load or how much warmth you brought into our house. But I know.” Graham reminisced, “Although many have commented on his complex character, perhaps I saw a side of that complexity that others did not see, for LBJ had a sincere and deeply felt, if simple, spiritual dimension.”

Johnson’s decision not to run for re-election in 1968 freed Graham to support his old friend Richard Nixon. Nixon credited him more than any other person for his decision to pursue the presidency again. Nixon remembered Graham telling him: “If you don’t run, you’ll worry for the rest of your life whether you should have, won’t you?”

In Nixon’s 1972 re-election bid, Graham, by his own admission, overstepped his boundaries. H. R. Haldeman mentioned several occasions when Graham participated directly in campaign strategy. When word of the Watergate scandal broke, Graham could not believe that his friend knew about it or took part in the cover-up. Not until a Christianity Today interview in early 1974 did Graham acknowledge that Nixon had made mistakes, though he continued to believe that Nixon would be exonerated.

When Graham read through the Watergate transcripts, he saw the gravity of Nixon’s misdeeds. Biographer William Martin wrote: “What he found there devastated him. He wept. He threw up. And he almost lost his innocence about Richard Nixon.”

Nixon’s pervasive profanity repulsed Graham. Eventually, Nixon’s deceptions got to him too: “I’d never heard him tell a lie. But then the way it sounded in those tapes—it was all something totally foreign to me in him. He was just somebody else.” Years later he acknowledged, “Nixon’s candidacy . . . muffled those inner monitors that had warned me for years to stay out of partisan politics. I could not completely distance myself from the electoral process that was involving such a close friend.”

In the crisis Billy Graham responded to critics with characteristic generosity and recommitted himself to nonpartisanship. Two comparatively brief presidencies gave him time to regroup. Though he knew Gerald Ford, he was careful to keep his distance. When he held a crusade in Pontiac, Michigan (Ford’s home state), Graham chose not to invite him to speak from the platform (a mistake he had made with Nixon). Ford did consult with Graham about pardoning Nixon, something Graham said was in the best interest of the country. He did not develop a close friendship with fellow Southern Baptist Jimmy Carter, though they both spoke later of strong mutual respect.

Graham found another longtime friend in Ronald Reagan. He saw Reagan as a man of “quick wit and warm personality,” and he respected “his insight and tough-minded approach to broad political issues.” Despite the renewal of Cold War tensions in the 1980s, Graham dreamed of preaching the gospel behind the Iron Curtain. Through a complicated and persistent strategy and with diplomatic influence, he realized that dream in 1982. Having the president of the United States as a close friend helped dramatically.

Gulf war blessing

Billy Graham’s relationship with the Bush family was almost three decades old by the time George H. W. Bush became vice president, and it became even closer as Bush made his run for the Oval Office. By the late 1980s, the “evangelical vote” had become very desirable, and this fact complicated their relationship. The staunchly Episcopalian Bush did not know how to present himself to evangelicals. He studiously avoided using Billy Graham for political gain, but also depended on him to understand this powerful voting bloc.

The Bushes deeply appreciated Graham’s transparent faith and fruitful ministry. They began inviting him to Kennebunkport for family gatherings. He often fielded questions about the Bible in after-dinner conversations. During one such session in August 1985, the topic of being born again arose, which caught the attention of George and Barbara’s eldest son, George W. Bush. The following day he and Graham took a walk on the beach. His presidential memoir credits that conversation as the significant turning point in his spiritual life.

By 1990 America appeared headed toward war in the Persian Gulf. In contrast to criticisms from prominent liberal clergy, Graham voiced public support for Bush’s policies. He also provided private support. When the war began in January 1991, Graham was a guest in the White House. Barbara Bush invited him to watch television with her that day, and he quickly realized that she wanted him with her as the war began. The president joined them, and Graham offered prayer. Years later, Bush said, “We wanted Billy Graham by our side.”

Diplomatic courier

Bill Clinton often credited Graham’s insistence on racially integrated crusades, which Clinton witnessed in Little Rock as a boy, as a significant factor in his decision to enter public service. As governor of Arkansas, he met Graham at the National Governor’s Conference in 1985. At Clinton’s inauguration in January 1993, Billy Graham offered prayer.

Clinton, like others before him, reached out to the evangelist for more than personal help. When Graham told the White House that he intended to visit North Korea in 1994, President Clinton engaged him to help ease tensions with Kim Il-Sung’s regime. Graham met with Kim as a kind of courier between heads of state.

Graham’s pastoral care for Clinton did not waver through the president’s highly publicized moral failings. In Graham’s memoir, Just As I Am, published at the end of Clinton’s first term, his pastoral compassion shone through as he described a conversation with Clinton: “It was a time of warm fellowship with a man who has not always won the approval of his fellow Christians but who has in his heart a desire to serve God and do His will.”

Perhaps because of the role Graham had played in George W. Bush’s spiritual renewal, he bent his rule about endorsements. On the cusp of Election Day 2000, news media fixed on Bush’s earlier problems with alcohol and irresponsible behavior. He was campaigning in Florida, and Graham was preaching a crusade there. A private conversation between them produced a public photo of candidate Bush with the evangelist. It could not have come at a better moment. We remember the 2000 election for “hanging chads” and its long-delayed resolution. Who can tell what this public moment with Billy Graham meant for Bush’s election?

In April 2010 President Obama visited Billy Graham at his Montreat home, making it 12 presidents that Graham has known and for whom he has prayed. By that time, Graham’s strength had waned and his public appearances had ceased, yet his influence remained strong. As a Christian leader he entered extensively into the circles of power and through all exemplified commitment to principle coupled with transparency. During a Newsweek interview in 2006, Graham offered this judgment: “Much of my life has been a pilgrimage—constantly learning, changing, growing and maturing.” The record reveals the truth of these words. CH

By Stephen Rankin

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #111 in 2014]

Stephen Rankin is chaplain of Southern Methodist University and author of Aiming at Maturity: The Goal of the Christian Life.Next articles

“Go forth to every part of the world”

Billy Graham’s early missions to Europe helped shape a global evangelical movement

Uta BalbierWatershed: Los Angeles 1949

The revival that took Billy Graham from anonymity to national fame

Grant WackerBilly Graham, Did you know?

Billy Graham’s political temptation, his friendships with entertainers and heads of state, and the impact of his music team

the editors