The Dark Ages? Think again

THE ROMAN EMPIRE in the second century AD stretched from southern Scotland to present-day Iraq. It gleamed with painted marble, and its economy bustled vibrantly. While it maintained its ancient republican institutions in name, in reality strong emperors ruled. A third of the Italian population lived in cities, where local aristocrats paid for public works out of their own pockets as a civic duty and to build their own prestige.

But in the late second century, crisis came. Philosopher-emperor Marcus Aurelius left power to a son who was an unhinged spoiled brat. His murder touched off a civil war, won by the general Septimius Severus, who took power. But Severus’s dynasty too went down in blood. The cycle repeated itself throughout the “terrible third century.”

Military pressures built on the frontiers. In the east, a new Persian dynasty, the Sassanids, challenged Roman claims. In the west, Germanic Goths migrated from present-day Ukraine and invaded the Balkan Peninsula. Out-of-control inflation and the collapse of Rome’s international trade networks shattered the economy.

Out of this crisis, a series of strong military emperors arose. They saw themselves as images of the gods from which all order and authority flowed. They separated military and civilian chains of command to decrease the power available to usurpers like those who had knocked off their predecessors. They passed laws binding people to the professions and land of their parents.

From outlaws to leaders

In previous centuries, Christians had been a marginal annoyance, just one among many dubious cults attracting the masses. But throughout the 200s Christians grew in numbers and influence. Under Diocletian (reigned 284–305), the only truly large-scale, deliberate, systematic persecution of Christians in the ancient world occurred. Constantine, his successor (reigned 306–337), was also concerned with order and unity. But he concluded that Christians, rather than being a threat to order, could hold the empire together by prayers, moral influence, and organization.

So Christianity became the empire’s official religion, and the church took on a new role as the moral glue of society. Bishops functioned as spiritual advisors to emperors, and as judges and community leaders. The empire, in turn, helped build grand and beautiful church buildings. Sharp tensions arose between the apocalyptic, otherworldly claims of the church and its new role as a force of social order.

By 400 the empire looked very different than it had 200 years earlier. It was much less urban. Local leaders who had built public buildings and paid for elaborate games to entertain their people now faced financial hardship. Aristocrats retreated to live in leisure on their great estates. Taxes crushed middle and lower classes. Little distinction held between slaves and free, as rural lower classes worked the same estates year after year. The burden of military service to guard the empire’s vast frontiers was too great to be borne by this declining population. So Romans hired soldiers from Germanic tribes who lived along the Roman frontier. Romans regarded these soldiers as inferior, and the soldiers often responded with violence and extortion in return. The leader of one tribe, the Goths, even sacked Rome in 410 after Rome refused his demands.

The eastern half of the empire, initially ravaged, managed to deflect these barbarians westward. The official date of the “fall” of the Roman Empire was 476, when Germanic warlord Odoacer overthrew boy emperor Romulus Augustulus (himself of barbarian origin). From 476 until Charlemagne’s coronation in 800, no Roman emperor had his capital in the west. But this seems more important to us than it did at the time. Emperors had not lived at Rome for some years. People didn’t think the empire ceased to be united just because it had several rulers. Nor did they think of it as fallen because there was no longer an emperor in the west. The emperors living in “New Rome,” the glorious Greek city built by Constantine and named Constantinople after him, would still rule in the east for nearly a thousand years.

Western authority now rested largely in the hands of barbarian warlords. Many had learned Roman ways and risen to high positions in the empire. But the sharp division between military and civilian authority structures segregated Germans and Romans. Germans were army, Romans civilians. In some territories laws forbade Romans to carry weapons. Germans held the power of the sword.

Germans brought a radically different culture. Roman society valued law and order, punishing crimes in the name of the sacred State. Germans valued personal dignity and honor, treating crime as a conflict between two people. In Germanic society, theft was punished severely, usually by amputation. Murder, on the other hand, often came from feuds between families. Executing the murderer only prolonged the feud. So instead a murderer paid weregild—monetary compensation to the family of the victim. Roman society put all authority in a family in the hands of the oldest male. Germans distributed property among a dead man’s sons (and to a lesser extent daughters). Territorial boundaries shifted with each generation. Germanic rulers were surrounded not by official bureaucracy but by a band of warriors who had sworn personal loyalty (think The Godfather).

Cities continued to exist, but few people lived in them. Buildings crumbled and ruins were hauled away. A world of marble and concrete was replaced by a world of wattle and clay. Scattered settlements were divided by forests roamed by wolves and wild boar. Power rested in the hands of warrior bands loyal to a leader who rewarded them with plunder.

This transition naturally appeared tragic later, and people labeled the time from the “fall” of Rome to the revival of urban society in the eleventh century the “Dark Ages.” But in fact many things continued just as they had been. The professional Roman army, for all its impressive armor and discipline, had been corrupt: soldiers supplementing a meager income by extorting money from civilians. Now Germanic warriors did the extorting. Peasants already tied to the land by the decree of Roman emperors now worked for Germanic masters. The new world took root inside the withering shell of the old, and when the shell fell away, people barely noticed. The primary source of continuity was the church, whose power remained based in Rome. Roman aristocrats furnished the western church with leadership. Steeped in classical culture and learning, with a strong sense of civic responsibility, they mediated between old and new. They spoke for the civilian Roman population to Germanic overlords, intervening in endless feuds among the new masters. Sixth-century bishop Gregory of Tours spent much time trying to keep members of the Frankish royal family from killing each other.

Initially, most Germanic tribes were Arians, who rejected the full divinity of Jesus. By 600 the Arian kingdoms collapsed or converted to Catholic Christianity. From the standpoint of the Catholic Church, pagan tribes were even more promising converts than Arian ones. In the fifth century Christian missionaries such as St. Patrick converted the Irish to Christianity, and the Irish sent out missionaries in turn. Around 600 Pope Gregory the Great sent the monk Augustine to England, where he established Canterbury as a Christian center.

An advancing tide

Typically, Christian missions began when Christian slaves or traders established a presence in a pagan country. (St. Patrick was initially taken to Ireland as a slave.) Pagan kings then married the daughters of Christian rulers, linking themselves to Roman Christianity’s economic and social prestige. With Christian queens came monks and priests, who began attracting converts. In time kings would usually agree to be baptized, followed by important warriors and, in some cases, nearly the entire population.

This initial conversion was often fragile and superficial. If a ruler with a different political agenda took the throne, or if a neighboring king launched a successful invasion, paganism might return for a time. But Christianity was like an incoming tide—it advanced and receded, but each wave came further than the one before.

With King Clovis (reigned 481–511) of the Frankish tribe, history turned a corner. Clovis, baptized in 496, chose to become Catholic rather than Arian. From Clovis on, Frankish kings—Charlemagne one day included—saw themselves as specially related to the bishops of Rome and the Catholic Church. But the relationship was rocky. The church disapproved of Frankish violence and refused to condone Frankish kings taking multiple wives (usually one at a time) and then divorcing them at will.

Meanwhile, another Christian force was arising: monasteries. Many monastics lived in uninhabited places as hermits. Others wandered the roads. But those who established communities—men and women joined by commitment to a common rule of life and the authority of an abbot or abbess—eventually transformed the medieval landscape most dramatically.

Benedict of Nursia (480–543) wrote the rule adopted by most western monastic communities. Like many western Christian leaders of the period, Benedict was a Roman aristocrat. He gave up his privileged lifestyle for radical asceticism, soon attracted followers, and founded the great monastery of Monte Cassino (in modern Italy), a center of learning and spirituality for centuries.

Benedict’s Rule taught monks to seek union with God not through ecstatic experiences or extreme self-denial but through a disciplined routine of work, prayer, and study. Monasteries soon dotted the landscape, providing education, the protection of strong walls, and prayer and spiritual guidance—and preserving the scholarship of the Middle Ages. As they spread Christianity throughout western Europe, they also spread the use of Latin and Roman culture. But even as they did, they translated Christian concepts into Germanic, Celtic, and Slavic terms, where Jesus, as in the Old Saxon epic Heliand, became a lord and the disciples his warriors.

Alongside the monasteries, hermits remained. All over Europe, holy men and women lived by wells or on mountains, talked to birds and beasts, gave spiritual counsel, and brought fame to their homes both in life and in death.

When Charlemagne stepped onto this stage, the Christian Frankish kingdom he inherited had already ruled for longer than all of US history. It was Roman, Germanic, and Christian; monastic and warrior; pagan and devout. Little did he know—though he might not have been unhappy—that this unique fusion would give Europe its shape for more than a thousand years to come. CH

By Edwin Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #108 in 2014]

Edwin Woodruff Tait is a contributing editor at Christian History.Next articles

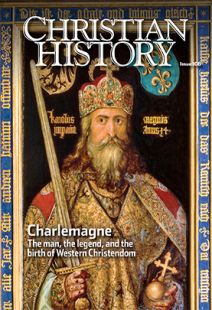

The man behind the empire

Charlemagne was a paradox: a warrior who fostered scholarship, a man capable of ruthless rule and devout piety

G. R. EvansCharlemagne vs. the Saxons

Were the Saxon wars really driven by the desire to convert these pagans?

G. R. EvansHow the Irish saved (Carolingian) civilization

Irish scholars, bards, and scientists were recruited to serve in Charlemagne’s court

Garry J. CritesSacred kingship

The coronation of Charlemagne entwined state and church from his day to ours

Christopher Fee