Sacred kingship

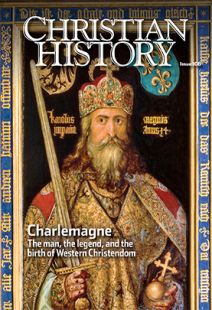

IT HAS ECHOED IN ART through the ages: Charlemagne, king of the Franks, at prayer in St. Peter’s Basilica before the tomb of the Apostle Peter on Christmas Day. Leo III, pope of the Roman Catholic Church, placing on his head a great jeweled crown and proclaiming him head of a Christian Roman Empire.

Then, a chronicle related, “all the faithful Romans, seeing how [Charlemagne] loved the holy Roman church and its vicar and how he defended them, cried out with one voice by the will of God and of St. Peter, the key-bearer of the kingdom of heaven, ‘To Charles, most pious Augustus [“the great”], crowned by God, great and peace-loving emperor, life and victory.’ This was said three times before the sacred tomb of blessed Peter the apostle, with the invocation of many saints. And so he was instituted by all as emperor of the Romans. Thereupon, on that same day of the nativity of our Lord Jesus Christ, the most holy bishop and pontiff anointed his most excellent son Charles as king with holy oil.”

On November 23, 800, Pope Leo had met the approaching Charlemagne 12 miles from Rome and accompanied him to the gates, evoking the entry of Caesar himself into Rome. Charlemagne then presided over the December 1 opening of a council in the Vatican that absolved of adultery and perjury no less a person than the pope himself. The same council originated (or confirmed) the decision to make Charlemagne emperor, for all that he later pretended to have been surprised about it.

The coronation ceremony blended Germanic kingship rituals, ancient imperial traditions, and Christian pomp and ceremony. The observers echoed ancient Roman custom and imperial law (which required “citizen witnesses”) when they acclaimed Charlemagne emperor. And Leo illustrated his subservience to the new emperor by performing the ancient ritual of bowing before a person of higher rank—in Leo’s case, flat on the floor on his face! But Leo still placed the crown on Charlemagne’s head—a reminder that while the emperor had divine right to rule, his temporal power was granted through the agency and authority of the pope. The lesson was not lost on Charlemagne.

Einhard suggested that he was annoyed: “[Charlemagne] came to Rome to restore the condition of the Roman church, which had been very much disturbed, and spent the whole winter there. At that time he received the title of emperor and Augustus, though he was so much opposed to this at first that he said he would not have entered the church that day had he been able to foresee the pope’s intention, although it was a great feast day.” Charlemagne saw that his last surviving son Louis did not make the same mistake in 813 when he joined his father on the throne as co-emperor. Charlemagne did not invite Leo to the coronation, or the party, and he crowned Louis himself.

Charlemagne became the central symbolic figure around which subsequent French kings and Holy Roman Emperors developed their own proof of their right to rule. Many subsequent coronations carefully echoed Charlemagne’s rituals. When the Capetian dynasty emerged (in the tenth century), it proclaimed its links with Charlemagne. And from the time of Louis XIII on, French coronation ceremonies employed objects associated with Charlemagne.

Tellingly, when Napoleon rose to power after the French Revolution, a thousand years after Charlemagne, he too self-consciously identified with the famous emperor. He used relics of Charlemagne in his own coronation. And, having learned from Charlemagne the need to subordinate the church while employing its pomp and power, Napoleon took care that it was he himself, not the pope, who placed the crown on his own head. He even announced to his ambassador to the Vatican, “I am Charlemagne.”

Holy kingship

Up until the coronation, Charlemagne’s title had been Rex Francorum, “King of the Franks.” This title had clear overtones of Frankish pride. The Franks viewed conquered peoples as subjects. They had no notion of broad citizenship within their borders as Romans had, which enabled many people—even freed slaves—to aspire to become Roman. Any notion of “Roman-ness” to the Franks was associated with the city of Rome and not with the historical Roman Empire. They saw themselves as having cast off the rule of the Romans, whom they did not revere.

The original title bestowed on Charlemagne, Imperator Romanorum, “Emperor of the Romans,” seems to have been as meaningless to Frankish nobles as it was offensive to Constantinople, the Byzantine capital and the seat of the eastern Roman Empire. But it soon changed to Romanum gubernans imperium, “[He is responsible for] governing the Roman Empire.”

This was intelligible and perhaps even impressive to the Franks, although hardly more palatable to Constantinople. Einhard wrote, “Nevertheless [Charlemagne] endured very patiently the envy of the [eastern] Roman emperors, who were indignant about his accepting the title, and, by sending many embassies to them and addressing them as brothers in his letters, he overcame their arrogance by his magnanimity.”

Charlemagne hoped that his coronation would mark the genesis of an Imperium Christianum, a “Christian Empire.” The Franks, unlike other Germanic tribes, were not Arians, but held the orthodox Trinitarian faith of Rome. They saw themselves as legitimate defenders of the “true faith.”

Charlemagne was trying to unify the far-flung and diverse regions he ruled in religious, rather than ethnic, terms: not the Frankish Empire, but what became the “Holy Roman Empire.”

And Charlemagne, according to Alcuin, his Anglo-Saxon court scholar and priest, was now the ultimate protector of all the churches of Christ. The transfer into Carolingian authority of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem in 802 suggests that even the Arab world recognized this status.

Pope, emperor, and the east

The papacy had maintained a long and complex relationship with Constantinople almost since the fall of the western empire in 476. The Byzantines had a military presence on the Italian coast right up to the time of Charlemagne. The Duchy of Rome itself was, at least in theory, Byzantine territory.

But by the time of Charlemagne, tensions between the pope and the Byzantine emperor were stretched to the breaking point. The Byzantines, occupied with Arab rivals, could spare little help against attacking Germanic tribes who repeatedly harried Rome. Charlemagne stepped into this power vacuum. When Leo became pope, he gave Charlemagne the keys of St. Peter’s tomb and the Banner of Rome, acknowledging him as Defender of the Holy See.

The council over which Charlemagne presided was part of this struggle. Leo had been temporarily deposed and maimed in 799 by politically powerful conspirators, who planned to blind him and cut out his tongue, a Byzantine practice used to end an adversary’s political power without outright murder. Leo escaped, and his enemies could not replace him without Charlemagne’s consent.

Although technically no one could stand in judgment over the pope, all parties agreed to the council. Leo was allowed to prove his innocence by taking an oath on the New Testament, but it is clear that it was Charlemagne’s support of Leo that mattered. His coronation sanctified that political reality.

But from the Byzantine perspective, Charlemagne’s coronation was the utmost in a long line of offenses against Constantinople, and the pope’s role in the ceremony a particular outrage. As Alcuin pointed out, both the Byzantine emperor and the pope had been humbled and savaged by their own inner circles. Charlemagne stood higher than both and had judged even the pontiff himself. By the time of the coronation, the pope owed his very life and office to the man he crowned emperor before St. Peter’s tomb. CH

By Christopher Fee

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #108 in 2014]

Christopher Fee is professor of English at Gettysburg College and the author of several books on medieval literature.Next articles

Christian History Chart: Not your parents’ Middle Ages

The Middle Ages had many renaissances before "The Renaissance"

the EditorsAlcuin of York

Alcuin reformed education at court and established a palace library

Jennifer Awes Freeman