Delighted in God

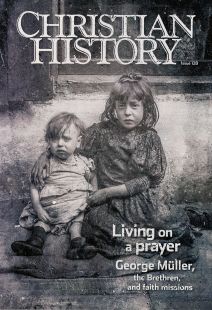

[Young George Müller]

IN JANUARY 1822 a police officer looked up from his desk in one of the old half-timbered buildings of Wolfenbüttel. The once glorious medieval castle now served as the town’s prison, where two soldiers stood guard over a handsome Prussian youth.

“What is your name?”

“George Müller.”

“Age?”

“Sixteen.”

“Place and date of birth?”

“Kroppenstaedt, Prussia, September 27, 1805.”

“Is it true that you have been living in style at Wolfenbüttel and that you are unable to pay the innkeeper? Is it also true that you spent last week at another hotel near Brunswick, living in similar luxury, and that when asked for payment you were forced to leave clothes as a security?”

The young man could say little in his defense; he was penniless and in debt. After three hours of questioning, the two soldiers marched him away to prison. The warden locked Müller in his cell day and night and gave him no work and no exercise. “Could I have a Bible to read?” Müller inquired to help pass the time. The answer was a sharp “No.”

pastoring for profit

In the silence Müller began to reflect on his life. His earliest memory went back to January in 1810 when, at the age of four, his family had moved from Kroppenstedt to Heimersleben where his father was appointed collector of taxes. Before his tenth birthday, he had begun to steal government money from his father. Herr Müller had hoped that George would become a clergyman: not to serve God, but to have a comfortable living.

In his Wolfenbüttel cell, George reflected on his five years at the cathedral classical school at Halberstadt and remembered—with some shame—a Saturday night two years prior, when he had played cards until 2:00 a.m. on Sunday morning. Then, having quenched his thirst at a tavern, he toured the streets with friends, half drunk, before attending the first of a series of confirmation classes.

On returning to his rooms, the 14-year-old found his father waiting for him. “Your mother is dead,” Herr Müller told him. “Get yourself ready for her funeral!”

In the 20 months following his confirmation, George spent some of his time studying, but a great deal more time playing the piano and guitar, reading novels, drinking in taverns, and alternately making and breaking resolutions for self-improvement.

On January 12, 1822, Müller’s reflections were interrupted when the heavy bolt of his cell slid open. “Follow me. Your father has sent the money you will need,” the police commissioner told him. “You are therefore free to leave at once.” Herr Müller welcomed his son home with a severe beating.

Müller’s great ambition was to enter Halle, the famous university that also happened to be the seat of Pietist theology and practice—a theology that emphasized new birth, personal faith in Christ, and the warmth of Christian experience.

Müller fulfilled his ambition in the spring of 1825, but the freedom of university life offered too many temptations; the 20-year-old was soon riddled with debt once more and had to pawn his watch and some clothes. He felt utterly miserable, worn out by his constant unsuccessful attempts to reform himself.

In one of Halle’s taverns (where he had once drunk 10 pints of beer in a single afternoon), Müller recognized Beta, a quiet and serious young man from his old school at Halberstadt. Müller reasoned that a close upright friend might help him to lead a steadier life. And he was right. Beta led Müller to the turning point of his life at the house of Beta’s friend Herr Wagner (read “Nothing but the blood of Jesus,” p. 13, for Müller‘s own description of his conversion).

That night Müller became a Christian. The next day after his conversion and on several days during the following week, Müller returned to Wagner’s house to study the Bible.

missionary vision

In January 1826 six or seven weeks after becoming a Christian, and after much prayer, Müller returned to his father with an important decision: “Father, I believe God wants me to become a missionary. I have come to seek your permission as is required by the German missionary societies.”

His father exclaimed, “I’ve spent large sums of money on your education hoping to spend my last days with you in a comfortable parsonage. And now you tell me that this prospect has come to nothing. I can no longer consider you as my son!” Müller returned to Halle and resolved to take no more money from his father for his remaining two years.

He also embarked on the task of proclaiming his new-found faith with the zeal that would characterize his life. He circulated missionary papers in different parts of the country, stuffed his pockets full of tracts to distribute, wrote letters to his former friends pleading with them to turn to Christ, and visited a sick man who eventually became a Christian.

However not all his early efforts at evangelism were entirely successful. He later wrote,

Once I met a beggar in the fields, and spoke to him about his soul. But when I perceived it made no impression on him, I spoke more loudly; and when he still remained unmoved, I quite bawled in talking to him; till at last I went away, seeing it was of no use.

In August 1826 a schoolmaster who lived near Halle approached Müller and asked him to preach in his parish. “I have never once preached a sermon,” Müller replied, “but if I could commit a sermon to memory I might be able to help you.” He stumbled through the memorized sermon early that Sunday, and repeated it word for word later in the morning.

In the afternoon he planned to use the same sermon a third time, but when he stood in the pulpit facing his congregation, he felt led to read from Matthew 5 and to make whatever comments came into his mind. As he began to explain the meaning of the words “Blessed are the poor in spirit,” Müller felt that he was being helped to speak. Whereas in the morning his memorized sermon had been too difficult for the people to understand, the afternoon congregation listened with great attention to his extemporaneous delivery.

In June 1828 Müller received a letter from the London Society for Promoting Christianity among the Jews (LSPCJ, later the Church Mission to the Jews). The committee had decided to take him as a missionary student for six months on probation, provided he would come to London.

Just one obstacle remained, however: every healthy male Prussian graduate was required to serve one year in the army. Müller had not yet done so. The solution to the problem was unexpected; Müller became seriously ill and was found to have a tendency to tuberculosis. One of the generals gave Müller a complete exemption for life from all military engagements.

In February Müller left Berlin for London, visiting his father on the way at the house in Heimersleben where he had spent his boyhood. After nearly a month’s delay, Müller arrived in London on March 19, 1829.

Characteristically he worked hard in London: for about 12 hours a day, he studied Hebrew, Chaldee, and the rabbinic alphabet. But the long hours of study took their toll, and the 23-year-old soon fell ill again. He felt sure he was dying, but an inner happiness prevailed:

It was as if every sin of which I had been guilty was brought to my remembrance; but, at the same time . . . I was washed and made clean, completely clean, in the blood of Jesus. The result of this was great peace. I longed exceedingly to depart and be with Christ.

But this departure was not to be just yet. As he recovered Müller took his friends’ advice and headed south to Devon for a change of air. And so it was that in Teignmouth, Devon, Müller struck up a friendship that would last 36 years and change the course of his life.

He met Scotsman Henry Craik (1805–1866) in the summer of 1829. Craik had also been converted while at university before becoming a private tutor in the home of Anthony Norris Groves. Groves had convinced Craik that Christ was speaking literally when he said, “Sell your possessions and give to the poor” (Matt. 19:21). (See “The simple standard of God’s word,” p. 29.)

Müller eagerly soaked up this teaching, describing his time in Devon as a “second conversion.” Upon his return to London in September 1829, Müller shared his enthusiasm with his colleagues. He organized a meeting every morning for prayers and Bible reading, at which each man present explained what God had shown him from the Bible portion he had read.

Toward the end of November 1829, Müller began to question his association with the LSPCJ. He was coming to the view that as a servant of Jesus Christ he ought to be guided by the Holy Spirit in his missionary work and not by people. One of the requirements of the committee would be that he should spend the greater part of his time working among the Jews. Müller felt called to preach as the Spirit led and sometimes to Gentiles.

He wrote to LSPCJ and received a letter that pointed out politely that the society couldn’t employ anyone who would not submit to its guidance. Severing this tie he was now free to put into practice his belief “a servant of Christ has but one Master” and to work whenever and wherever his master directed him.

as long as he felt God’s call

In late 1829 Müller was invited to become the pastor at Ebenezer Chapel in Devon, a call that came with a unanimous request from the entire congregation. After a great deal of prayer, Müller agreed, making it clear that he would stay only as long as he felt God’s call to minister in that place.

In 1830 Müller went to preach at Sidmouth and got embroiled in an argument about believer’s baptism with three women. They convinced him that his childhood baptism was invalid. After studying the entire New Testament, Müller decided that baptism was for believers only and that total immersion was the scriptural pattern. Some time later Henry Craik baptized him, and almost all of his friends followed suit.

News of the able young Prussian spread rapidly. In the summer of 1830, Müller led Ebenezer Chapel to follow the example of the apostles in Acts 20:7 and observe the Lord’s Supper every Sunday, although he admitted there was no specific commandment to do so. He also put into practice lessons received from Ephesians 4 and Romans 12 to give room for the Holy Ghost to work through any brother in Christ whom He pleases to use. . . . At certain meetings any of the brethren will have an opportunity to exhort or teach the rest, if they consider they have something to say which may be beneficial to the hearers.

Throughout that summer Müller never refused an opportunity to visit Exeter. It wasn’t only the beauty of the journey; the attraction lay at the end of the journey in the form of Mary Groves, sister of Norris Groves. Müller felt sure that it was better for him to be married and had prayed much about the choice of a life partner. Mary Groves shared his earnest devotion to the Lord and the conviction to trust God for material supplies.

On August 15 Müller wrote asking her to be his wife; four days later he spoke to her in person. Mary accepted his proposal and they fell to their knees asking God to bless their marriage.

no pew rents

Soon after returning to Teignmouth, the newly married couple decided that it was wrong for George to receive a set salary. Müller abandoned pew rents (where people paid a set amount to reserve a seat in church) and made all seats free; at the end of October, he placed a box in the chapel with a notice saying that anyone who was led to support Mr. and Mrs. Müller might put their offerings therein. Müller also decided that from that time onward he would directly ask no one, not even his fellow Christians at Ebenezer Chapel, to help him financially in any way.

Soon Craik asked Müller to come to Bristol. On April 19, 1832, Müller preached the last of his weekly sermons in Devon, and the following day left to join Craik at Bristol to pastor Gideon Chapel.

The two men insisted on three conditions: that they would preach and work as they themselves interpreted God’s will, not according to a fixed pastoral relationship governed by rules; that pew rents should be abolished; and that they would continue the practice they had established at Teignmouth with regard to their financial support.

That summer cholera broke out in Bristol, reaching horrifying proportions by mid-August. More than 200 people met at 6 a.m. in Gideon Chapel to pray for relief from the suffering. In the midst of all this danger, Mary Müller was due to have a baby. As labor began she became very ill—though her illness was not cholera—and Müller spent a whole night in prayer. The next day Mary gave birth to a daughter, Lydia, who would be their only child to survive infancy.

In 1834 Müller and Craik founded The Scriptural Knowledge Institution for Home and Abroad (SKI), which still flourishes today. The three aims of the institution were (1) to assist and establish day schools, Sunday schools, and adult schools for teaching Scripture; (2) to distribute Bibles; and (3) to aid missionary work. Within the first seven months, SKI educated hundreds of children and adults and sent a thousand Bibles and £57 (over $7,500 today) to foreign missionaries.

But Müller wanted to do more.

In 1835 orphanages supported by private charity were rare, and those that did exist were small and explicitly for middle-class children. When Müller first arrived in Bristol, he had been deeply moved by the sight of children begging in the streets, and when they knocked on his door, he longed to do something positive to help. But he had another equally important motivation for his orphanage work: he wanted to demonstrate the power of God to the world.

On the evening of December 9, 1835, Müller spoke at a meeting outlining his proposals for the Children’s Home (see “Did you know?,” inside front cover). The next day a friend arrived at the Müllers’ home with three dishes, twenty-eight plates, three basins, one jug, four mugs, three salt-stands, one grater, four knives, and five forks. These would be the first of thousands of unsolicited gifts for the orphans’ care.

Gifts continued to arrive in the new year. On the evening of January 5, Müller’s house-bell rang. A servant opened the door, not to a visitor but to a kitchen fender (fireplace screen) and dish, left, no doubt, by a donor with strong views on anonymous giving. Müller was so encouraged by the support that in April he rented 6 Wilson Street and furnished it for 30 girls between the ages of 7 and 12 who would be trained to make a living in domestic service.

orphans aplenty

On April 11, 1836, the first children arrived, looking pale and nervous. In October 1836 Müller rented another house and furnished an Infant Orphan Home for boys and girls under seven. In June 1837 he opened a third home for about 40 boys aged seven years and above, partly because the need was so obvious but also because he needed a place to send the infant boys when they reached seven.

By the end of 1837, 81 children and 9 full-time staff sat down to meals at the three homes. There were enough applications to fill another home with girls aged seven and above, and many more applications for infants than they were able to accommodate. In addition 350 children were taught in the day schools of SKI, and 320 children attended the Sunday school.

Müller’s churches were also booming. When Müller and Craik had arrived in Bristol in 1832, they found fewer than 70 regular attendees at Gideon Chapel, and took charge of Bethesda Chapel as an empty building. During 1840 they gave up Gideon Chapel; Bethesda Chapel alone now had well over 500 members. In the next 30 years, the numbers would double to more than 1,000. American Bible teacher and author A. T. Pierson later described Bethesda as one of two truly apostolic churches he knew.

By the spring of 1841, Müller felt in need of a change. When a gift of £5 for his own expenses arrived, he interpreted it as a sign to leave Bristol for a while. So he traveled to Gloucestershire, where he began a new spiritual practice. Up until that time, he had been in the habit of getting straight down to prayer every morning. But while on this vacation, he adopted the view that the most important thing was to concentrate on first reading and meditating on the Bible.

In October 1845 Müller received what he described as a “polite and friendly” letter from a resident of Wilson Street complaining of the noise the children made (there were now four homes). After much prayer Müller felt that it was God’s will for him to embark on his boldest venture of faith yet: to build a brand new home specifically meant for an orphanage. He asked his fellow workers at Bethesda Chapel their opinions, and all eight agreed. George and Mary began to pray over the matter, and, as soon as they were sure that it was the Lord’s will, they started to ask him for the necessary funds—at least £10,000 (equal to about $43,500 at the time; it would be over $1.3 million today).

In February 1846 Müller bought seven acres at Ashley Down for half the market value. It took four years to accumulate funds and to build a home for 300 children, plus staff and teachers. On June 18, 1849, the first excited children spilled out onto Wilson Street and made their way to Ashley Down. They enjoyed the sound of the birds singing, the sight of cows grazing in the fields, and the view across the valley toward Stapleton. Inside even the fresh paint and newly polished woodwork smelled good, and the whole place was bright and well ventilated.

expanding faith

Just two years later, in 1851, Müller began thinking of expanding again, but skeptics doubted whether he could get support to double the work. But in the years that lay ahead, Müller would startle the world by tripling the size of his work while continuing to rely on prayer and the gifts of supporters. On January 6, 1870, the last of Müller’s great buildings on Ashley Down, “New Orphan-House No. 5,” was opened.

During the final years of the expansion, Mary’s health failed. Müller tried to persuade her to work less and eat more, but she said to him,

My darling, I think the Lord will allow me to see the New Orphan-Houses Nos. 4 and 5 furnished and opened, and then I may go home; but most of all I wish that the Lord Jesus would come, and that we might all go together.

Not many days after the opening of No. 5 in January 1870, Mary—now 73—caught a heavy cold that developed into a deeper illness. On February 6 she died. Müller knelt by the bed and prayed: “Thank you for taking her to be with Yourself. Please help and support us now.”

That same year he told his associate James Wright (1837–1905) that he considered it to be God’s will that Wright should succeed him as the orphan homes’ director. Eighteen months later, the newly widowed Wright also asked for the hand of Lydia Müller in marriage. Müller recorded: “I knew no one to whom I could so willingly entrust this my choicest earthly treasure.” They were married at Bethesda on November 16, 1871: Wright was 45 and Lydia 39. Wright later described their life together as a time of “unbroken felicity.”

Several weeks later George Müller married Susannah Grace Sangar, a governess from Clifton about 20 years his junior. He called her “a consistent Christian . . . I had every reason to believe that she would prove a great helper to me in my various services.”

Since coming to Bristol in 1832, Müller had preached almost exclusively in that city. But now several gifted and experienced men could shoulder responsibilities at Bethesda Chapel, and Wright had proved himself an able codirector of SKI and the orphan homes. After much prayer Müller decided to devote his closing years to a worldwide work of preaching and teaching. He and Susannah toured and preached in European countries as well as Russia, the United States, Canada, Australia, India, Japan, Egypt, Palestine, Turkey, and Greece.

In Greece they found time to visit the Areopagus on Mars Hill, and to stand on the spot where Paul preached his famous sermon (Acts 17:16–34). They explored the Acropolis and saw the ruins of the many ancient idol temples that had so stirred the heart of the apostle 1,800 years earlier. In 17 years George and Susannah traveled about 200,000 miles visiting 42 countries. In 1892 when they ceased traveling, Müller was 87.

temporary partings

During their travels, while at Jubbulpore, India, Müller learned that his only child, Lydia, had died on January 10, 1890, at 58. He described the news as a “heavy blow” but took comfort from Romans 8:28. The Müllers returned to England by the first suitable steamer from Bombay. Four years later, in 1894, Müller’s journal notes without warning:

It pleased God to take to Himself my beloved wife [Susannah], after He had left her to me twenty-three years and six weeks. By the grace of God I am not merely perfectly satisfied with this dispensation, but I kiss the hand which administered the stroke, and I look again for the fulfilment of that word in this instance, that “in all things God works for the good of those who love Him” (Rom. 8:28).

Müller was again a widower.

On Sunday morning, March 6, 1898, he spoke at Alma Road Chapel on John 12, Jesus’s Holy Week journey, mentioning Christians’ bright prospect. The following Wednesday he told James Wright he felt weak and needed rest, but in the evening, he led the usual weekly prayer meeting in Orphan Home No. 3 concluding with the hymn “We’ll Sing of the Shepherd that Died.”

Next morning, March 10, 1898, he awoke between five and six o’clock, got up, and walked toward his dressing table. And then that bright prospect of which he had spoken in his sermon just four days earlier became—for him—glorious reality. George Müller saw his lovely One. C H

By Roger Steer

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #128 in 2018]

Roger Steer is the author of the classic biography of Müller, Delighted in God, from which this article is adapted with the kind permission of Christian Focus. He has also written many other biographies of Christian leaders.Next articles

Nothing but the blood of Jesus

Müller speaks of his conversion when he was a divinity student at the University of Halle.

George Müller