Francis Asbury, Did you know?

No zip code needed

At the height of his career, Francis Asbury (1745–1816) was so famous that one need only write on a letter “Bishop Francis Asbury, United States of America” and the letter would reach him. More than a thousand children are known to have been named after him; if you have a Frank or Francis in your family tree, you may have Asbury to thank. He was more widely recognized by the common people than anyone else from his era—including George Washington and Thomas Jefferson.

Dead cats and snorting pigs

Asbury was born in England and began his preaching career there. Bedfordshire, the circuit on which he preached (a circuit was a series of towns or villages assigned to a single preacher) was very hostile to Methodists. Mobs frequently assaulted Methodist preachers.

One preacher was hit on the head with a dead cat. In another house people met in a room above a pig sty to hear preaching, and a relative of one of the listeners dropped food to the pigs during preaching services, hoping that the pigs would make so much noise that the Methodists would shut up. In the end, the Methodists out-shouted the pigs and kept going.

Startling statistics

When Asbury first came to the American colonies as a 26-year-old Methodist missionary in 1771, there were 600 Methodist believers on the new continent. Fewer than 1 in 800 people was a Methodist. When he died in 1816, there were over 200,000 Methodists (1 of every 36 Americans), and Asbury had ordained over 2,000 Methodist preachers, nearly all of those who were preaching at the time. Despite poor health, he had ridden over 130,000 miles and preached for 45 years (an average of eight miles per day), probably delivering more than 10,000 sermons—approximately one sermon every three days.

Traveling light and with an open hand

Asbury never married or owned much more than he could carry on horseback. He told Henry Boehm, one of his traveling companions, that “the equipment of a Methodist minister consisted of a horse, saddle and bridle, one suit of clothes, a watch, a pocket Bible, and a hymn book. Anything else would be an encumbrance.” George Roberts, another preacher, recorded that Asbury left New York for Boston on one trip with only three dollars in his pocket and refused to take more from anyone on the way.

Setting the gospel free

Presbyterians, Anglicans, and members of other more established churches would have been surprised by the expanded roles for women and African Americans in Methodist services, even in mixed gatherings. Though this support was always complicated—discrimination against “African” worshipers led both Richard Allen (see “My chains fell off,” p. 21) and James Varick to found African American branches of Methodism—there were times and places where both groups exhorted fellow believers, prayed in public, and even preached. Ironically, as Methodism’s mainline grew more sophisticated and wealthier, such times and places grew fewer. Allen, shortly before his death, mused:

I am well convinced that the Methodist has proved beneficial to thousands and ten times thousands. It is to be awfully feared that the simplicity of the Gospel that was among them fifty years ago [is fading], and that they conform more to the world and the fashions thereof. . . . The discipline is altered considerably from what it was. We would ask for the good old way, and desire to walk therein.

Treasures in saddlebags

When Asbury died, he left his books and papers to his successor, Bishop William McKendree (1757–1835). Preacher Jacob Young was assigned to carry the items across the Allegheny Mountains to McKendree, and he loaded them on Asbury’s horse.

Along the way on an isolated part of the trail, Young was accosted by men who believed that the packages he was carrying must contain silver or other valuables. They asked him where he had come from. “Baltimore,” said Young. One of the robbers scoffed, “Is money plentiful there? You seem to have plenty of it here.” Young replied that he carried no valuables but that his horse and luggage belonged to Bishop Asbury, who was now dead. “Is Bishop Asbury dead?” asked the robber. “I have seen and heard him preach in my father’s house.” The two bandits galloped off without stealing a thing.

Prophet and builder

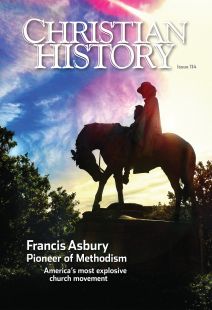

A statue of Asbury on his horse stands to this day in Washington, DC, at the corner of Mount Pleasant and 16th Streets. (Similar statues also stand in Madison, New Jersey, and Wilmore, Kentucky.) It was dedicated in 1924 at a ceremony attended by thousands of people and presided over by President Calvin Coolidge, who remarked in his speech that Asbury “is entitled to rank as one of the builders of our nation.” Besides Asbury’s name, the statue bears these inscriptions of tribute:

His continuous journey through cities, villages, and settlements from 1771 to 1816 greatly promoted patriotism, education, morality, and religion in the American republic.

If you seek for the results of his labor you will find them in our Christian civilization.

The prophet of the long road. CH

Some of this material was adapted from American Saint: Francis Asbury and the Methodists by John Wigger.

By the editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #114 in 2015]

Next articles

Editor's note: Francis Asbury

Methodism’s beginning in America was many things I had not expected

Jennifer Woodruff TaitMethodists and their stuff

Methodists have collected thousands of documents, objects, records, and artifacts

Christopher J. Anderson