Food, Did you know?

I’m eating—you’re not

The Bible mentions over 50 foods (see “Good food from the good book,” p. 11) and also discusses abstaining from food, especially food offered to idols.

Early church documents lay down other fasting rules: the first-century Didache says, “Let not your fasts be with the hypocrites, for they fast on Mondays and Thursdays, but you fast on Wednesdays and Fridays.”

Ovo-lacto-pesca-vegetarians?

Standardizing which foods to avoid while fasting took a while. In the late 300s, Epiphanius of Salamis (c. 310–403) described a myriad of fasting practices:

Some abstain altogether from meat, whether of four-footed animals or birds or fish, as well as from eggs and cheese. Others only abstain from four-footed creatures, but eat birds and the other categories mentioned. Others again refrain also from birds but continue to eat eggs and fish, while yet others abstain from these too and only permit themselves cheese. Again, others do not use cheese either. Certain people even abstain from bread, and others from fruit that grows on trees, and from all cooked food.

Red eggs in the morning

One of the customs that characterizes Greek Orthodox Easter celebrations is the making of red-dyed eggs, kokkina avga, as symbols of the Resurrection. They are eaten with Easter bread, tsoureki (see recipe for a version of this on p. 41) and are also used to play a game called tsougrisma which involves tapping eggs together and trying to break your competitors’ eggs.

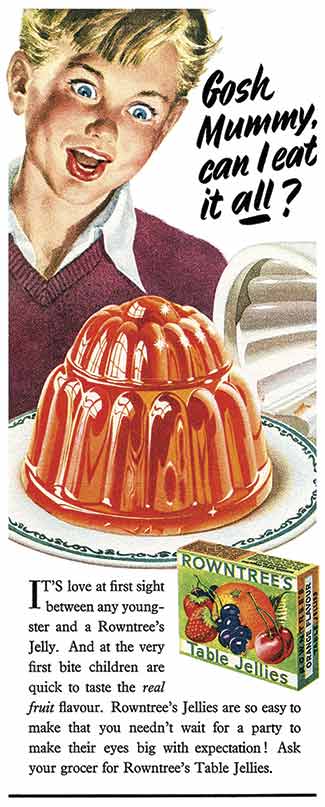

Feasts of love and Jell-O

The word “potluck” dates to the sixteenth century, when it first meant a meal provided on short notice for unexpected guests.

The custom now called love feasts largely died out after the fourth century. It was revived in the 1700s by Schwarzenau Brethren, Moravians, and Methodists (for more, see “From Cana to Jell-O,” pp. 42–44). Moravians used coffee, tea, and sweet bread; Brethren combined soup and meat with foot washing and Communion; and Methodists ate bread and water. But the focus was the same: the sharing of testimonies, singing, and prayer, combined with a simple meal.

Feast on wine and fast on water

A much-quoted description of Catholic attitudes toward food and drink is attributed to Hilaire Belloc (1870–1953):

Wherever the Catholic sun doth shine,

There’s always laughter and good red wine.

At least I’ve always found it so.

Benedicamus Domino!

Belloc’s friend G. K. Chesterton (1874–1936) wrote in “The Song of Right and Wrong,”

Feast on wine or fast on water.

And your honour shall stand sure,

God Almighty’s son and daughter.

He the valiant, she the pure;

If an angel out of heaven

Brings you other things to drink,

Thank him for his kind attentions,

Go and pour them down the sink.

The blood of Christ, in a cup for you

Ever wonder where individual Communion cups came from? Both grape juice and individual cups were introduced into Protestant practice in the late 1800s (for more, see “Raise a juice box to the temperance movement,” pp. 33–35). In the 1890s Methodist pastors Charles Forbes of New York and Edward Ryan of Michigan independently designed cup trays and machines to fill them.

Speeding up Communion

In 2001 retired engineer Wilfred Greenlee invented a juice-dispensing machine for the megachurch he attended, Southeastern Christian Church in Louisville, Kentucky. It reduced the time for filling 350 Communion trays from 30 hours to one and a half hours. CH

By Thanks to those who contributed tidbits, including Kristen Roth Allen, Elesha Coffman, Suzanne Estelle-Holmer, Martha Manikas-Fo

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #125 in 2018]

Next articles

Letters to the editor, CH 125

Readers respond to Christian History

Editor's note: Food

If you took food out of your church’s weekly activities, many of those activities would look very different—or they’d simply disappear.

Jennifer Woodruff Tait