Did you know?

Cheaper by the dozen

One of the ways the MacDonald family made enough money to spend winters in Italy for George MacDonald’s ill health was to dramatize Pilgrim’s Progress and other literary works in their home. Since George and his wife, Louisa, had 11 children (he jokingly referred to his brood as “the wrong side of a dozen”), there was no need to go outside the family for actors. Louisa adapted and produced the plays (an 1875 copy of Pilgrim’s Progress containing their tour schedule resides at the Wade Center at Wheaton College, Wheaton, Illinois, today), and their eldest daughter, Lilia, a talented actress, starred. When the MacDonalds toured the United States in 1872—George lectured on Robert Burns, Shakespeare, and Tennyson—Greville, their oldest son, accompanied them. He often had to produce family pictures to convince unbelieving audiences that the petite Louisa really had given birth to so many children.

Treasure in tweeds

C. S. Lewis’s personal appearance—an old tweed coat with baggy flannel pants and a floppy fisherman’s hat—was at odds with fan impressions. According to biographer A. N. Wilson, Lewis once agreed to meet with a priest to discuss the man’s doubts about the Christian faith. Said Wilson, “The priest, who had expected the author of The Problem of Pain to look pale and ethereal, was astonished by the red-faced pork butcher in shabby tweeds he actually encountered.” Lewis’s chauffer Clifford Morris told how Lewis lost one hat on a picnic: “On the way to Cambridge, at the beginning of the next term, we looked inside the field gate where we had picnicked, and there was the hat, under the hedge, being used as a home for field mice. Jack retrieved it, of course, and later on continued to wear it.” Warnie Lewis, his brother, also told a hat story: “It is said that Jack once took a guest for an early morning walk on the Magdalen College grounds . . . after a very wet night. Presently the guest brought his attention to a curious lump of cloth hanging on a bush. ‘That looks like my hat,’ said Jack; then, joyfully, ‘It is my hat.’ And, clapping the sodden mass on his head, he continued his walk.” Lewis refused to spend extra money on clothes (or on anything else) and gave away his book royalties. In fact, he was surprised to find that he had to pay taxes on the royalties even after he had given them away; to avoid this, Owen Barfield, his lawyer as well as his friend, set up a philanthropic trust fund.

Guess who didn’t do the shopping

As a journalist G. K. Chesterton wrote over 100 books and 4,000 newspaper articles, often dictating two articles at once to his secretary while waving a swordstick for dramatic effect. Yet his absent-mindedness is legendary. One day he misplaced his pajamas while traveling. When his exasperated wife, Frances, asked, “Why did you not buy a new pair?” he replied plaintively, “Are pajamas things that one can buy?” He also supposedly telegraphed Frances from a lecture tour: “Am in Market Harborough. Where ought I to be?” His letters to Frances are also legendary. One, about her mother’s financial objections to their marriage, contains this paragraph: “When we set up a house, darling . . . I think you will have to do the shopping. . . . There was a great and glorious man who said, ‘Give us the luxuries of life and we will dispense with the necessities.’ That I think would be a splendid motto to write . . . over the porch of our hypothetical home. There will be a sofa for you, for example, but no chairs, for I prefer the floor. There will be a select store of chocolate-creams . . . and the rest will be bread and water. We will each retain a suit of evening dress for great occasions, and at other times clothe ourselves in the skins of wild beasts (how pretty you would look) which would fit your taste in furs and be economical.”

Not so easy to marry off

Dorothy L. Sayers meant to end her successful series of Lord Peter Wimsey mysteries sooner than she actually did. She wrote of introducing Peter’s love-interest, Harriet Vane: “Let me confess that when I wrote Strong Poison, it was with the infanticidal intention of doing away with Peter; that is, of marrying him off and getting rid of him.” But: “I could find no form of words in which [Harriet] could accept him without loss of self-respect. . . . She must come to him as a free agent, if she came at all, and must realize that she was independent of him before she could bring her dependence.” It took another three novels and five years of “story time”—Have His Carcase, Gaudy Night, and Busman’s Honeymoon—before the two were successfully wed.

Preaching a sermon to students

Despite Charles Williams’s unassuming—even ugly—personal appearance and lack of a university education, he was a dynamic speaker. Lewis and Tolkien arranged for him to give over 40 public lectures in Oxford during the time he was living there. In a 1940 letter to his brother Warnie, Lewis wrote: “On Monday [Charles Williams] lectured nominally on [Milton’s] Comus but really on Chastity.” Williams, unlike most modern critics, really cared about virginity, delivering what Lewis called a “sermon” on its importance: “It was a beautiful sight to see a whole room full of modern young men and women sitting in that absolute silence which can NOT be faked, very puzzled, but spell-bound: perhaps with something of the same feeling which a lecture on unchastity might have evoked in their grandparents—the forbidden subject broached at last. . . . That beautiful carved room [in Oxford] had probably not witnessed anything so important since some of the great medieval or Reformation lectures. I have at last, if only for once, seen a university doing what it was founded to do: teaching Wisdom.”

Letters on a grave

J. R. R. Tolkien’s works have created a community among his admirers—a community still reflected at his gravesite. An American literature professor found the following collection: “dead roses and lots of dead flowers, a brilliant red rosary hanging from a rosemary bush, lavender, letters (lots), books, coins (lots from everywhere), thank you notes, bracelets, cigarettes, runes (really), hairbands, drawings, a wood carving with a dragon and runes, butterflies (artificial), sunglasses, rocks, buttons, watercolors, pages from a book, prayer cards, poems, business cards, crosses, a medallion, ribbons, locks of hair, a framed tribute in Spanish titled ‘Viejo professor’ [old professor], notes in perfect Elvish script, and now, a bracelet I got in Pamplona during the festival of San Fermin. And it’s now missing one rose bud. “This seems like a lot, and you’d think it would be garish and trashy. Not at all; it seems very sweet and just about right.” CH

By the editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #113 in 2015]

the editorsNext articles

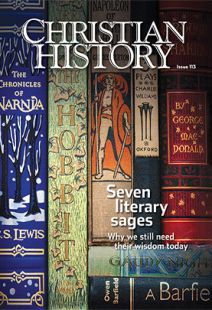

Editor's note: Seven literary sages

How much did C.S. Lewis and his friends and mentors change the society around them?

Jennifer Woodruff TaitBread of the earth and bread of heaven

G. K. Chesterton (1874-1936) wanted a new kind of Christian economics

Ralph C. WoodSayers “begins here” with a vision for social and intellectual change

Sayers was asked to compose a wartime message

Crystal DowningWhy hobbits eat local

J. R. R. Tolkien (1892-1973) and his friend Lewis shared an ideal of remaining rooted on the land of God’s good creation

Matthew Dickerson