Sayers “begins here” with a vision for social and intellectual change

WHEN G.K. CHESTERTON DIED, Dorothy L. Sayers wrote to his widow saying, “G. K.’s books have become more a part of my mental make-up than those of any writer you could name.” Chesterton’s Orthodoxy (1908) prevented Sayers from abandoning Christianity during her adolescence, and his insights later informed her education at Oxford University.

In 1913 Sayers read Chesterton’s What’s Wrong with the World (1910), and the next year she attended several of his Oxford lectures. Chesterton laid the groundwork for Sayers’s analysis of what was wrong with her world.

Already famous for her Lord Peter Wimsey detective stories, Sayers was asked to compose a wartime message in September 1939. Begin Here appeared only four months later (and included a quote from Chesterton). In her preface, she noted: “This book does not pretend to offer any formula for constructing an Earthly Paradise: no such formula is possible. It suggests only that there is at present something incomplete about the average human being’s conception of himself and society, and that the first step towards constructing the kind of world he wants is to decide the kind of person he is, and ought to be.”

Sayers’s book outlined how views of human nature had changed in the modern era, when biological, sociological, psychological, and economic explanations of behavior replaced theological ones. Though endorsing the theological worldview, she noted that the church’s capitulation to political agendas had contributed to its subsequent idolization of reason and “progress.”

She wrote decades before today’s postmodern challenges to the Enlightenment‘s sanctification of reason. But Sayers anticipated today’s troubles with the modern era’s emphases on reason and progress. She suggested that unquestioned belief in progress often leads to violence: for instance, Marxist faith in communism and German belief in national socialism.

However, while many contemporary postmodern texts emphasize the deconstruction of such modernist absolutes, Begin Here encouraged the creative construction of something new. Sayers wanted to nudge people out of their passivity, to get them to think independently rather than conform to cultural dogmas.

Exhorting people to analyze what they read, to discuss with others different works on the same topic, and to compare multiple viewpoints, she asserted that “words . . . can change the face of the world.”

Not just the facts, ma’am

Sayers knew that the words of Chesterton had changed the face of her own world. As she explained in a 1954 letter, “If I am not now a Logical Positivist, I probably have to thank G. K. C.” Sayers’s attraction to logical positivism, a philosophy that held that only empirically verifiable facts can ground truth, explains why, in 1947, she dismissed Begin Here as “a very rush job, undertaken much against my will,” with factual “errors and omissions.”

Little did she know that Begin Here would foreshadow our eventual attack on the “just the facts, ma’am” attitude. One day postmodernists would echo her insight that “with the abandonment of an absolute Authority outside history, the seat of absolute authority within history tends to become identified with the seat of effective power.”

Thanks largely to Chesterton, Sayers’s solution to the arbitrary absolutes and power of secular culture was the divine authority of Christian orthodoxy: an absolute transcending all culturally contingent dogmas. She would have reminded us that the creative work of contributing to culture, as an expression of the image of God, the imago Dei, must therefore always begin here, with these words: “In the beginning, God created.”

By Crystal Downing

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #113 in 2015]

Crystal Downing is Distinguished Professor of English and Film Studies at Messiah College (PA) and writes on the relationship between Christianity and culture.Next articles

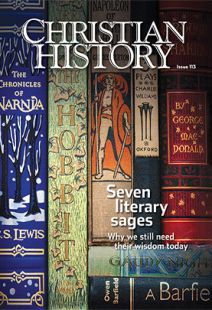

Why hobbits eat local

J. R. R. Tolkien (1892-1973) and his friend Lewis shared an ideal of remaining rooted on the land of God’s good creation

Matthew DickersonMeeting Professor Tolkien

He laughed at the idea of being a classical author while still alive

Clyde S. KilbyChristian History timeline: Biographies of the seven sages

Brief biographies of our featured authors

Matt Forster