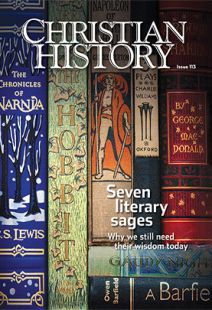

Christian History timeline: Biographies of the seven sages

GEORGE MACDONALD

Few writers in English have influenced the genre of fantasy literature as much as George MacDonald. His novels pulled back the curtain on magical worlds and inspired Lewis Carroll, C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, and Madeleine L’Engle.

Born in 1824 in Scotland, MacDonald attended Aberdeen University and then Highbury College, a school in London for training Congregational ministers. For three years he served as pastor of Trinity Congregational Church in Arundel, in the south of England. Less Calvinistic than the denomination he served, he left pastoral ministry and depended on writing and tutoring to provide for his large family.

Poor health led him to move his family to the Italian Riviera for 20 years. Highly respected by his literary peers, MacDonald counted among his acquaintances novelists Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, and Anthony Trollope. He also came to know Mark Twain, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow while touring in America.

Fantasy and fairy tales are often considered “juvenile” fiction, but MacDonald proved the critics wrong as he used the genre to explore Christian themes and explicate the human condition.

• Born December 10, 1824, Huntly, Aberdeenshire, Scotland

• Died September 18, 1905, Ashtead, Surrey, England

• Married Louisa Powell (m. 1851)

• Children Lilia, Mary, Caroline, Greville, Irene, Winifred, Ronald, Robert, Maurice, Bernard, George

• Selected Works

• Phantastes (1858)

• The Princess and the Goblin (1872)

• The Princess and Curdie (1883)

• Lilith: A Romance (1895)

G.K. CHESTERTON

A generation separated the Inklings from the life of George MacDonald. The interim years, however, were not devoid of writers who viewed culture through the eyeglasses of faith. One of the best known for this role is G. K. Chesterton, artist and literary critic. He authored not only entertaining whodunits (there are over 50 Father Brown mystery stories) but also some of the most compelling Christian theology of his time for lay readers.

Born in London in 1874, Chesterton attended St. Paul’s School, after which he went to the University of London where he studied art and literature without earning a degree in either subject. Chesterton’s career began when he found work in a London publishing house. Not long after, he began working as a freelancer, writing articles on art and literature. This led to a job with the Daily News and eventually a position with the Illustrated London News, where he was a columnist for 30 years.

Chesterton was known for his good-natured personality and imposing physical presence. Often caricatured as obese, he stood six foot, four inches tall and weighed 286 pounds. A natural debater, he did not hesitate to argue in print and in person with the luminaries of his day. Most famously, he debated playwright and social critic George Bernard Shaw, whom he considered a friend.

While Chesterton’s reputation as an author of fiction orbits around his novels (especially The Man Who Was Thursday) and the Father Brown stories, his true legacy may turn out to be Orthodoxy and The Everlasting Man. These two books have become classics of Christian apologetics. Though Chesterton was an Anglican turned Roman Catholic, a wide spectrum of Christians read his books today.

• Born May 29, 1874, Kensington, London, England

• Died June 14, 1936, Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, England

• Married Frances Blogg (m. 1901) (no children)

• Selected Works

• Orthodoxy (1908)

• The Man Who Was Thursday (1908)

• The Everlasting Man (1925)

• The Father Brown mysteries (51 stories, written from 1910 to 1936)

J.R.R. Tolkien

To the general movie-going public, J. R. R. Tolkien is well known. As the creator of Middle-earth and author of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, he enjoys an exalted place among fantasy novelists. Many authors look back to first reading about hobbits and wizards as the spark that launched their own creativity.

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was born in South Africa to British parents, Arthur and Mabel. His father worked for a bank based in England. When he was three, his mother took him and his younger brother, Hilary, to England to visit family. While they were away, his father died. His mother, left to rely on the financial support of her family, converted to Roman Catholicism, much to the disappointment of her Baptist relatives who then refused further funds. When Mabel died in 1904 from complications of diabetes, her close friend Fr. Francis Xavier Morgan took in John (12) and Hilary (10). Tolkien remained a committed Catholic throughout his life.

Forever fascinated by lan guages—he created them even as a child—Tolkien’s first job after World War I service was researching the etymology of words for the Oxford English Dictionary. He later became a professor of philology (the study of how language works) and wrote a vocabulary for Middle English. Tolkien’s novels are heavily indebted to his work as a philologist.

Meanwhile he had worked on a private mythology for years, but without real intentions to publish fiction. He had to be persuaded to submit The Hobbit, originally written for his children, to publisher Allen and Unwin. The success of the book and a demand for more led him to write The Lord of the Rings, set in the invented landscape he had been developing in his spare time for so long.

Since Tolkien’s death his son Christopher has edited and published much of his father’s manuscript work —most recently, a translation of Beowulf.

• Born January 3, 1892, Bloemfontein, Orange Free State, South Africa

• Died September 2, 1973, Bournemouth, England

• Married Edith Bratt (m. 1916)

• Children: John, Michael, Christopher, Priscilla

• Selected Works

• Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (1925, ed. with E. V. Gordon)

• “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics” (1936)

• The Hobbit (1937)

• The Lord of the Rings (1954–1955)

• The Silmarillion (1977, posthumously, ed. Christopher Tolkien)

Dorothy L. Sayers

Readers familiar with the golden age of detective fiction (1920s–1930s) rank Sayers’s urbane protagonist, Lord Peter Wimsey, among the era’s great fictional sleuths. Sayers wrote 11 Wimsey books, beginning with Whose Body?, but her literary output extended past well-crafted whodunits.

One of the first women to be awarded a degree from Oxford, Dorothy Leigh Sayers began her adult life writing poetry and teaching, until she found her way to advertising copywriting in 1922. She is still remembered for jingles for brewer Guinness (including “Guinness is good for you”) and for coining the phrase, “It pays to advertise!”

Sayers helped found the Detection Club, a group of mystery writers who discussed the ins and outs of the craft; G. K. Chesterton was its first president. In the 1930s Sayers turned to playwriting and was commissioned to write a ground-breaking series of plays on the life of Christ for BBC Radio. A lifelong Anglican, she reluctantly took up lay apologetics, penning calls to authentic Christianity like Creed or Chaos? (1940). She considered her translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy, with commentary highlighting Christian themes, one of her greatest accomplishments, but died before finishing Paradise, the third volume.

• Born June 13, 1893, Oxford, England

• Died December 17, 1957, Witham, England

• Married Oswald Atherton “Mac” Fleming (m. 1926)

• Children: John Anthony (from a relationship Sayers had in the early 1920s)

• Selected Works

• Peter Wimsey novels from Whose Body? to Busman’s Honeymoon (1921–1931)

• The Mind of the Maker (1941)

• The Man Born to Be King (1941)

• Dante’s Divine Comedy (trans. 1949–1962, completed by Barbara Reynolds)

C . S . Lewis

Clive Staples Lewis (known as “Jack” to his friends) was born in Ireland in 1898. He fought in the World War I trenches and was wounded. At Oxford he studied Greek and Latin literature, philosophy, ancient history, and English. In 1925 he became a fellow and tutor in English literature at Oxford’s Magdalen College.

Though raised in a Christian home, as a young boy Lewis embraced atheism. But, as he described in his autobiography, Surprised by Joy, God’s pursuit of him eventually led to his acceptance of theism in 1929 and Christianity in 1931. Books such as Chesterton’s The Everlasting Man and MacDonald’s Phantastes, and conversations with friends such as Tolkien, Barfield, and H. V. D. Dyson (all of whom would one day be members of the Inklings) helped him rediscover faith. He returned to his childhood Anglicanism.

Lewis’s academic work revolved around his schol arly interest in the late Middle Ages, but his prolific output was hardly limited to the subjects he taught at Oxford. His first published work of fic tion was The Pilgrim’s Regress, a Christian allegory. This was followed by the Space Trilogy, The Screwtape Letters, The Great Divorce, and The Chronicles of Narnia—all with undeniably Christian themes. During World War II, he gave a series of BBC Radio addresses on the essentials of the Christian faith, later adapted into a classic of Christian apologetics, Mere Christianity.

Late in life Lewis met Joy Davidman, an American divorcee with two sons. As friends, they married in a civil ceremony so that Davidman could continue to live in England when denied a visa. But the relationship deepened, and after Joy developed bone cancer, they obtained a Christian marriage. When Joy died Lewis chronicled his experience of bereavement in A Grief Observed.

Lewis died on November 22, 1963, his passing overshadowed by the assassination of John F. Kennedy on the same day.

• Born November 29, 1898, Belfast, Ireland

• Died November 22, 1963, Oxford, England

• Married Joy Davidman (m. 1956)

• Children: Stepfather to David and Douglas Gresham

• Selected Works

• The Pilgrim’s Regress (1933)

• The Allegory of Love (1936)

• Out of the Silent Planet (1938)

• Perelandra (1943)

• That Hideous Strength (1945)

• The Problem of Pain (1940)

• The Screwtape Letters (1942)

• The Chronicles of Narnia (1950–1956)

• Mere Christianity (1952)

• Surprised by Joy (1955)

• The Discarded Image (1964)

Charles Williams

Educated for a time at University College London, Charles Walter Stansby Williams left school for financial reasons before obtaining a degree. From this inauspicious start, he eventually found himself as a proof reading assistant for Oxford University Press. He took the position in 1908 and for nearly four decades continued to rise through the ranks, his remarkable tenure ending only on the occasion of his early death in 1945.

Williams’s literary out put was impressively diverse: poetry on Arthurian themes, numerous plays, literary criticism (especially The Figure of Beatrice, a study of Dante), biographies, and theology. He is perhaps best known for his fiction—a collection of supernatural fantasy thrillers set in the contemporary world. His works are filled with ghosts, demons, magic-wielding relics such as a pack of tarot cards and the Holy Grail, and Platonic archetypes. Williams was a lifelong Anglican. His works of Christian theology include He Came Down from Heaven and The Descent of the Dove.

Mutual admiration between Williams and C. S. Lewis, along with the relocation of Oxford University Press offices to Oxford during World War II, led to Williams’s participation in the Inklings. On his death, Warren Lewis (Jack’s brother) wrote: “There will be no more pints with Charles: no more ‘Bird and Baby’ [their favorite pub]: the blackout has fallen, and the Inklings can never be the same again.”

• Born September 20, 1886, London, England

• Died May 15, 1945, Oxford, England

• Married Florence “Michal” Conway (m. 1917)

• Children: Michael

• Selected Works

• War in Heaven (1930)

• Many Dimensions (1930)

• The Place of the Lion (1931)

• The Greater Trumps (1932)

• Shadows of Ecstasy (1933)

• Descent into Hell (1937)

• He Came Down from Heaven (1938)

• The Descent of the Dove (1939)

• The Figure of Beatrice (1943)

• All Hallows’ Eve (1945)

Owen Barfield

For more than four decades, C. S. Lewis and Owen Barfield argued and debated as friends. Barfield graduated from Wadham College, Oxford, with a degree in English literature in 1920 and became a poet and author. During this period he heard a lecture by Rudolf Steiner and became an anthroposophist. Though baptized as an Anglican in middle age, he also held anthroposophical beliefs until his death. (Anthroposophy seeks to achieve mystical experiences under scientific control.) Many of his books blend history and philosophy. His most famous, Saving the Appearances, details the evolution of consciousness. His novel Worlds Apart depicts a fictional dialogue about belief between a physicist, biologist, theologian, philosopher, psychiatrist, teacher, rocket scientist, and lawyer. Several appear to be based on members of the Inklings.

Barfield continued writing throughout his life, but in 1934 began a 25-year career in law, working as a solicitor in London. He was Lewis’s solicitor and trustee, managing his friend’s sizable gifts to charity.

• Born November 9, 1898, London, England

• Died December 14, 1997, Forest Row, England

• Married Maud Douie (m. 1923)

• Children: Alexander and Lucy; fostered Jeffrey (Corbett) Barfield

• Selected Works

• History in English Words (1926)

• Poetic Diction (1928)

• Romanticism Comes of Age (1944)

• Saving the Appearances (1957)

• Worlds Apart (1963)

• Owen Barfield on C. S. Lewis (1989)

By Matt Forster

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #113 in 2015]

Matt ForsterNext articles

The poetic vision of a connected world

The difficult works of Charles Williams (1886-1945) tell of self-giving love and mystical union

Brian HorneWas the oddest Inkling the key Inkling?

It was often Williams's agitated intellect, fertile imagination, and physical energy that moved things along

Thomas Howard