Was the oddest Inkling the key Inkling?

Surely not. That palm must go to Lewis or Tolkien. But in an odd sense, it was often his agitated intellect, wildly fecund imagination, and sheer physical energy that moved things along. It was Williams, for instance, who rushed in and out of the room at The Eagle and Child fetching ale for everyone. His electric mind kept things humming, though often when he read from his works, he left the assembled company scratching their heads.

Tolkien was not especially fond of Williams. He maintained that he never knew what Williams was “on” about. But when Williams died suddenly, Tolkien had a Mass said for him, and himself acted as server to the priest, a noble tribute.

When he lectured, Williams would pop about, sitting on the edge of the desk with legs all tangled up, then jumping off, jingling coins in his pocket, and generally keeping things stirred up. He did not have much in the way of looks, but women were magnetically attracted to him, and he had some more-than-peculiar associations (see his Letters to Lalage). However, after almost 50 years of reading Williams and everything about him, I am convinced he went to his grave faithful in all senses to his wife, Florence, whom he had (typically) named “Michal”—after Saul’s daughter. Why? Because he was Williams.

Williams never stopped scribbling. He wrote feverishly, on the backs of envelopes, on tickets, and on any odd slips of paper he could put his hands on. W. H. Auden said that, when he first tried to read Williams’s poetry, he couldn’t make head or tail of it, but he read Williams’s quirky history of the church [The Descent of the Dove] once every year.

Williams flitted about the edges of the Roman Catholic Church like a moth, at least in his writings; but he lived and died an Anglican. He loved to draw on the sumptuousness of Catholicism for his imagery: terms like Our Blessed Lord, Our Lady, and the Mass. He may have had early associations with the Rosicrucians and certainly used arcane and mystical objects frequently. He never called Jesus Jesus: it is Messias, usually. And God comes on stage as “The Mercy” or “The Omnipotence.”

Williams’s whole theme, in all of his work, is courtesy—that is, the courtesies fitting for citizens of the City of God. Caritas. My life for yours. Exchange and substitution that pour down from the mysteries of the most Holy Trinity, through the cross, to you lending me a hand with my grocery bags—or refusing to do so. Heaven vs. hell, really.

By Thomas Howard

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #113 in 2015]

Thomas Howard is the author of The Novels of Charles Williams. This article is adapted from CH 78.Next articles

So great a cloud of witnesses

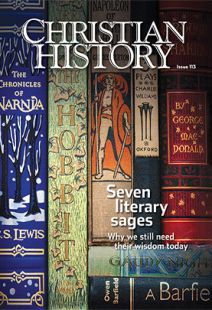

Some connections and influences among the seven sages

By Jennifer Woodruff Tait and Marjorie Lamp MeadSeven sages: recommended resources

With seven influential authors and scores of books by and about them, where should one begin? Here are suggestions compiled by our editors, contributors, and the Wade Center

the editorsFrancis Asbury, Did you know?

Without Francis Asbury, the American landscape would look very different

the editors