The emperor and the desert

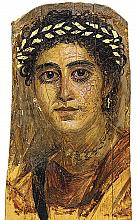

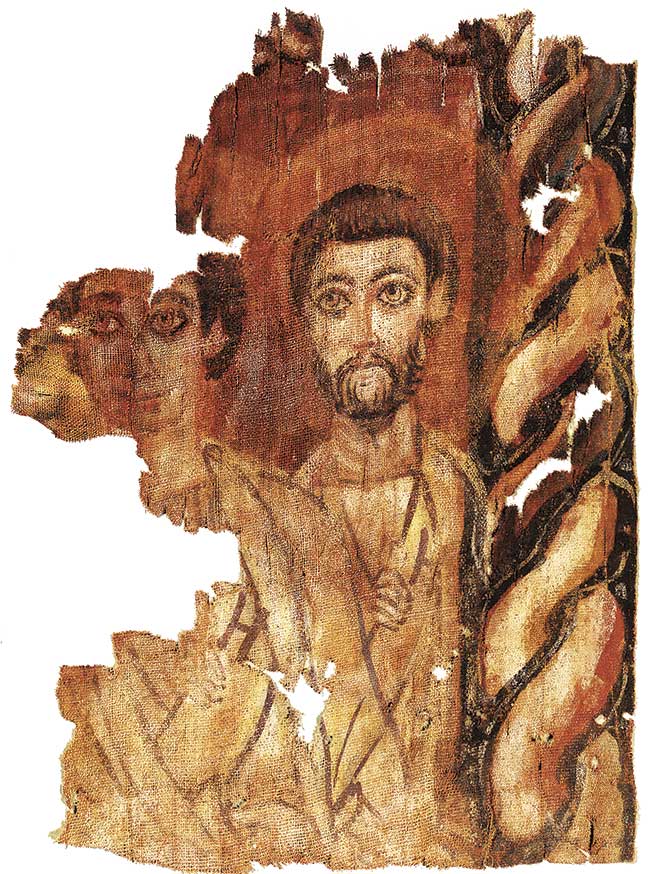

[Painting of two monastic men, 5th to 6th century Made in Egypt. Linen and paint—Bequest of Nanette B. Kelekian, 2020, Metropolitan Museum of Art]

A half-century after the death of Constantine, a visitor to Oxyrhynchus, a royal city of the pharaohs that had become a regional capital of Egypt in the Roman period, could see how swiftly the new imperial Christianity had changed the landscape of cities and towns. What would have surprised a time-traveler from the pagan years would not, however, have been the city’s religious zeal—or even the fact that it was so zealously Christian.

Fertile soil

Egypt had long offered fertile soil for larger-than-life religious developments. It was here that the Red Sea had been parted, here that Emperor Hadrian’s favorite courtier had drowned in the Nile and been proclaimed a god. That the Christian God turned out to be more powerful than Isis and Osiris had perhaps come as a surprise to the people of Oxyrhynchus, but surprises of this kind were not unusual.

But no one could have predicted the presence of 10,000 monks and 20,000 virgins in Oxyrhynchus. A heroic few had chosen to strike out on their own in the desert as solitaries, while the majority joined organized communities numbering in the thousands.

If modern estimates of the city’s population are accurate, this means that roughly a quarter of the city’s population took vows to remain unmarried; among these, women outnumbered men two to one. What could account for so many young women choosing to give up marriage and motherhood, and for so many of their parents failing to insist on grandchildren?

The ideals of sexual renunciation and retreat from pursuing the pleasures and hopes of this world were not new. The apostle Paul had argued in the first century that by giving up the dream of raising children, people of faith could show how ardently they hoped for the end of time and the coming of the kingdom of heaven. It was an invitation to live each day as if it were the last. As he wrote to the Corinthians: “Because of the present crisis, I think that it is good for a person to remain as he is. Are you pledged to a woman? Do not seek to be released. Are you free from such a commitment? Do not look for a wife” (1 Cor. 7: 26–27).

Readers often imagine that Paul intended to found a new value system based on ambivalence toward love and sex, but nothing could be further from the truth. Plans for the future were irrelevant, he believed, because the end of time was at hand. The Corinthians must prepare to lose the things they love. But they should not grieve: attachments here on earth are only a dim reflection of a love that is deeper and more permanent.

This profound statement reflected a harsh practical reality. Ancient families living long before the invention of antibiotics faced a daunting mortality rate. A sudden fever could carry off any member of a household within hours. This was all the more true in a harbor city like Corinth, where each new boat brought pathogens against which the local population had yet to build up resistance. The bonds of love and family created a constant threat of loss.

But at the same time, most of the New Testament writers assumed that marriage and child-rearing would be the norm for the majority of Christians, as for anyone else (see pp. 17–20). Early Christians participated in a society that revolved around families.

Paradoxes of conversion

Constantine’s conversion changed all of this. For the first three centuries, affiliation with the Christian movement was illegal, even if authorities turned a blind eye. During this period Christian leaders had been comparatively humble individuals who knew it was not in their interest to attract unnecessary attention, but who could be counted on to exhibit fortitude in the face of trials.

Paradoxically Constantine’s conversion now presented the most insidious challenge Christian churches had yet faced. What were Christians to make of a situation in which their bishops were now the emperor’s favorites?

The end of persecutions and the widespread acceptance of Christianity became, curiously enough, a source of disappointment for many. Increasingly bishops warred with their congregations and with one another, arguing about matters ranging from the mundane to the mystical. Money was often at the root of the problem (see pp. 12–15), and this was distressing. If bishops were quarreling over money, it is not surprising that many of the faithful wanted no part of it.

Ascetic renunciation allowed Christian communities to raise up new heroes of the faith at just the time when they most sorely needed inspiration. But this new challenge was all the more threatening because of its moral complexity. Was it right for the churches to accept the emperor’s favor, knowing that if they did so, they also tacitly accepted his right—so evident in all other aspects of life in the Roman Empire—to call the shots?

To be fair the believers never really had a choice. When Constantine perceived that the God of the Christians could help him gain and govern the empire, the earthly representatives of that God found themselves in a position not very different from that of a slave who catches the eye of his or her master, with the resulting benefits and dangers. Christians quickly discovered that a bishop or other leader who stood against the will of the emperor would soon be replaced. So the new interest in asceticism came at a time when many Christians were reassessing their relationship to the compromises of the institutional church.

The enthusiastic participation of women was one of the driving forces of this ascetic revolution, and it offered them surprising opportunities—as virgins, widows, and pilgrims, and also as nuns. Even senatorial daughters in Rome and Constantinople who simply never married and quietly transformed their households into living temples of virginity were inspired by, and did what they could to support, the wanderers and cave-dwellers of the Egyptian desert.

The economics of asceticism

From the late first century, Christian communities had offered economic support and an institutional structure for economically vulnerable unmarried women and widows. In the third century, evidence shows that both men and women began living in organized ascetic communities.

Some have argued that this communalism formed out of an organized Christian response to the threat of famine. The economy stabilized after 284 under Emperor Diocletian, who reorganized the structure of the Roman provinces to establish clearer lines of accountability and restore order. These policies developed further under Constantine.

At least some of the early ascetic communities organized in a way that allowed them to undertake charitable functions. By the early fourth century, they served as orphanages where this was practical, filling a glaring gap in Roman provisions.

Even when one or both parents were living, impoverished families often gratefully placed children with the monks or virgins so that what little they had could be distributed among a smaller number. Evidence suggests that more prosperous families began to send their children to monks or nuns for education. Whether by becoming an ascetic or by showing support for this movement, ordinary Christians could take a stand against the greed and corruption that threatened to erode the values of the church in its new, privileged circumstances. And the monks and virgins of the fourth century did not disappoint. Their willingness to sacrifice themselves for the kingdom of heaven was just as fierce as that of the martyrs before them.

Egypt became the heartland of this austere ascetic tradition. The desert proved an appropriate place for this life not only because it was empty, but because it was harsh. The unbearable heat in the summer turned to bitter cold on winter nights: even the piercing wail of the desert winds was chilling.

The fathers and mothers of the desert courted these extremes. Thirst, hunger, and sleeplessness challenged them most, but so did the deprivation of family and the constant struggle to give up one’s pride. Such a life only made sense if one had chosen it for a reason. Yet for those who had, its hardships offered an incomparable opportunity to test and cultivate the power of the human spirit.

Women faced an additional challenge, managing not only their own spiritual progress but also the constant tension caused by men’s anxiety about their presence (male and female communities were often established near each other). Sexual temptation does not figure nearly as strongly in the sayings of the desert mothers as it does in those of the desert fathers. Given the balance of power in ancient society, this makes a certain amount of sense. Women were accustomed to making substantial efforts to please men, while men tried comparatively less hard to please women.

For the men, by contrast, even chaste affection among family members could pose an obstacle to spiritual progress—the innocent company of a mother or a sister could become the source of a craving for emotional intimacy so powerful that it was difficult to suppress. One of the most revered abbots of fourth-century Egypt, Pachomius the Great, refused to see his sister Maria when she came to visit him. He felt an urgent need to avoid someone who might entangle him in the bonds of family feeling and was even praised for his self-control in being able to forgo the pleasure of her visit.

Athletes of Christ

Those who did not join ascetic communities respected the choices of those who did. Devout believers remaining in society viewed virgins, both nuns and monks, as having made a worthy and admirable choice to live with their eyes fixed on the world to come. The presence of such individuals in a community, they believed, brought value even to those who did not participate directly.

An anonymous rule book for monks and virgins written in Egypt between 350 and 450 argued that each of the children in every household should be educated in the love of virginity, with careful attention to discover “which among [the] daughters is worthy of holiness.” And the author of the anonymous homily “On Virginity” wrote: “In every house of Christians it is needful that there be a virgin, for the salvation of the whole house is this one virgin.” Parents were in the best position to instill a love of virginity in their children; at the same time, they could assess whether such aspirations were realistic. It was by no means certain that all Christian parents happily saw this as their responsibility, but at least some bishops wished that they would.

By the late fourth century, asceticism had moved from the fringes to become an ideal acknowledged by almost everyone. When Jovinian, a monk from northern Mesopotamia, argued that marriage and virginity were equally worthy vocations in the sight of God, synods in both Rome and Milan swiftly condemned his argument as heresy. Eminent married Christians defended Jovinian, since his view represented the more traditional strand of Christian thought.

But famed ascetic Jerome warned his protégée Eustochium to avoid the company of married women, even Christian married women. “Learn of me a holy arrogance,” he told her. His memorable phrase called attention to the gap that at least some were beginning to perceive between simple Christian laity—even those of exalted rank—and the set-apart “athletes of Christ.” CH

By Kate Cooper

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #147 in 2023]

Kate Cooper is professor of history at Royal Holloway, University of London, and author of Queens of a Fallen World: The Lost Women of Augustine’s Confessions, The Fall of the Roman Household, and Band of Angels: The Forgotten World of Early Christian Women, from which this article is adapted with the permission of Abrams Press.Next articles

Questions for reflection: Everyday life in the early church

Reflect on life among the earliest followers of Christ

the editorsRecommended resources: Everyday life in the early church

Read more about everyday faith in the early church in these resources recommended by our authors and THE CH TEAM.

the authors and editorsDid you know? Lilias Trotter

Lilias Trotter’s life intersected many trends in Victorian art, culture, mission, and service work

the editors