Extraordinary becoming ordinary

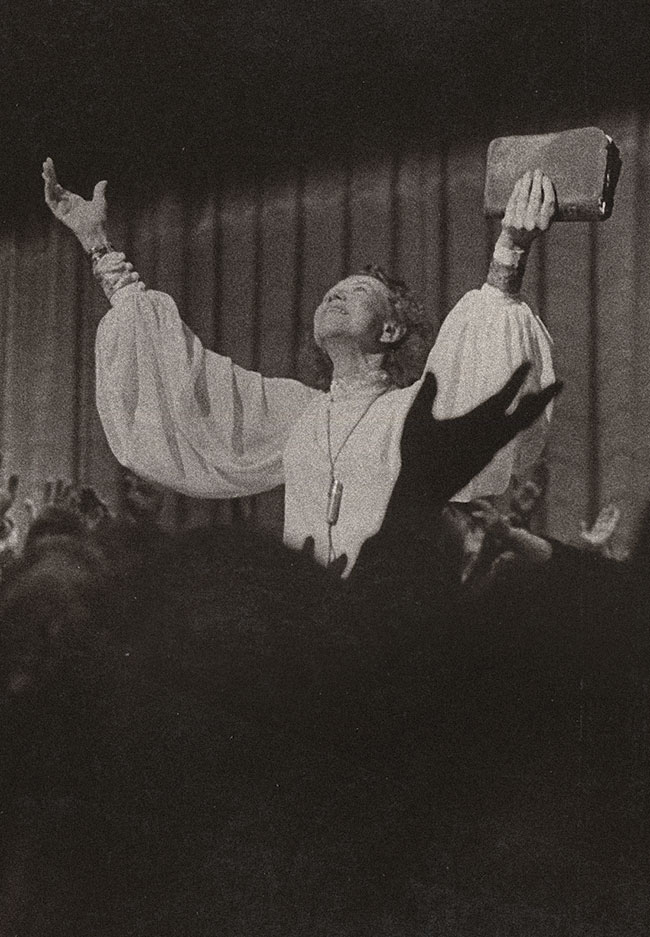

[Kathryn Kuhlman—Courtesy of Buswell Library Archives & Special Collections, Wheaton College, IL]

In 1968 popular healing evangelist Kathryn Kuhlman (1907–1976) welcomed Presbyterian minister Donald Shaw to her syndicated show. Kuhlman asked Shaw about his visit to one of her Miracle Services at Carnegie Hall in Pittsburgh. Shaw had attended after receiving a copy of Kuhlman’s best-selling I Believe in Miracles (1962) from a lay preacher during a “dry period” and said that he had struggled with pride at the service. “What would my colleagues think of me?”

“Brother, you’re nuts”

Shaw had seen a concert hall filled with people streaming to the stage to testify to divine healings taking place right in front of his eyes. “I prayed, ‘Dear Lord, whatever it is, I want it.’ I received new faith, new hope, new life. I went down under the power of God at the Miracle Service.”

“Did you know it was the power of God?” Kuhlman asked. He responded, “It is hard to say. . . . It happened so quickly. But if anybody at that time had told me that I, Donald Shaw, a very proud Presbyterian and an intellectual, would be lying there on my back in Carnegie Hall, before all of those people . . . my self-consciousness gone, gloriously happy and for the first time in my life experiencing this kind of joy, I would have said, ‘Brother, you’re nuts.’”

Kuhlman added happily, “A dead Presbyterian minister came alive in Christ!”

Shaw would have called himself a member of the new “Charismatic” movement, which practiced a “softened” version of Pentecostal theology. Charismatics retained the emphasis on the present reality of the spiritual gifts mentioned in Acts, particularly healing, but did not insist on speaking in tongues to prove the presence of the baptism of the Holy Spirit. And they made every effort to move Charismatic Christianity from the marginalized Pentecostal realm into Hilton ballrooms and elite bastions of ecumenical Christianity.

Charismatics came from a multitude of backgrounds and remained members of their denominations even as they participated in the movement. Organizations such as the Full Gospel Businessmen’s Fellowship International, founded by Demos Shakarian in 1951, provided meeting places and events for socially and financially successful Charismatic Christians.

In 1959 Episcopal priest Dennis Bennett reported to his congregation in Van Nuys, California, that he and his wife had experienced the baptism of the Holy Spirit during a prayer meeting and had spoken in tongues. The resulting controversy caught the eye of Time and Newsweek, gaining national media attention for the movement. In some ways the movement was everywhere; in other ways, nowhere—with no designated leader, structure, or defining identity. Cells seeking spiritual renewal emerged simultaneously in many groups, affecting almost all denominations.

Kuhlman was one of the movement’s most prominent evangelists. During a 55-year ministry, she preached to hundreds of thousands of people—in the last 10 years of her life at monthly services to capacity crowds in the 7,000-seat Los Angeles Shrine Auditorium. She also hosted radio and television shows, headed a successful nonprofit, and authored best sellers; I Believe in Miracles, a collection of healing testimonies, sold over a million copies. Gaining national exposure for Charismatic Christianity, she transformed it from overlooked, suspect, and fringe to a respectable practice accepted and even celebrated by mainstream Christianity and American culture.

In the early months of 1967, Catholic Charismatic revivals occurred on the campuses of Duquesne University in Pittsburgh and the University of Notre Dame. Strongly influenced by the Second Vatican Council, Catholic lay faculty and students began to organize prayer groups and sponsor retreats that encouraged and affirmed Charismatic experiences. When the press covered an April 1967 gathering at Notre Dame, the Catholic Charismatic renewal was officially underway.

These Catholic clergy and laity delighted in the movement’s emphasis on a “unity of the Spirit,” considering themselves the answer to the prayer of Pope John XXIII (1881–1963) at Vatican II for “a new Pentecost.” They joined with Episcopal and Lutheran leaders who were reclaiming their churches’ historic emphasis on prayer for healing. By the end of the 1970s, most major denominations in America had adopted “cautious openness” regarding the growth of Charismatic practices in their congregations. The adjective “Charismatic” now modified Episcopalians, Lutherans, Methodists, Presbyterians, American Baptists, Disciples of Christ, and Roman Catholics.

By the 1980s many Charismatics left behind their denominational or Roman Catholic associations to form independent churches and denominations of their own, making Charismatic Christianity a dominant form of Christianity in America. It spread through evangelical churches via music and worship style, and influenced prosperity gospel teaching (see pp. 47–49), which focuses on the power of positive prayer for wealth and wellness. Most directly it moved into the Vineyard movement (see pp. 41–43), which now has over 500 congregations and a prodigiously successful worship music division.

In the early 1970s, Kuhlman interviewed David du Plessis (1905–1987), a South African affiliated with the American Assemblies of God, to discuss the Charismatic movement’s growing ecumenism. They visually represented the movement’s variety as they sat together on white wicker chairs in Kuhlman’s faux-garden set, sharing their vision of a soon-coming time when “every gift will be restored” and “miracles will happen all the time.”

At the end of the episode, Kuhlman turned to the camera and proclaimed, “I am speaking to clergy: You can’t stop it. Don’t fight it. Come on in. If Jesus could trust the Holy Spirit, then surely you and I can. It makes no difference whether you’re Catholic or Protestant.” Sometimes, she might have said, the Spirit even brought dead Presbyterians to life. CH

Doctor for Christ

Kuhlman welcomed many medical doctors to witness to the reality of divine healing. In 1969 Dr. Kahn Uyeyama, associate clinical professor of medicine at the University of California Medical Center, said that prior to his own baptism in the Holy Spirit, he would have “laughed” about divine healing claims: “I was a humanist and an agnostic. I didn’t really believe in God. I would have tried to explain [them] away.” Based on his own evaluation of humanity and a study of Karl Marx’s works, he had believed “man was going to raise himself up by his own boot-straps to divinity.” But then he became convicted of Christianity’s truth: “The Lord wanted me to speak in tongues. . . . I thought tongues were gibberish. I had to be made a fool for Christ. I was allowed to sing in a strange language. I never sang—I couldn’t carry a tune, I would never sing in public. . . . Many of my patients have been divinely healed since I was baptized in the Holy Ghost. I have seen many miracles.”

Catholic renewal

Catholic priest Francis MacNutt (1925–2020) was baptized in the Holy Spirit in 1967 through the influence of Agnes Sanford (1897–1982). She said that the enthusiastic, compassionate Dominican would take supernatural healing to the Catholic Church worldwide, a prediction rapidly proved accurate. Nuns, priests, bishops, and laypeople embraced his nontraditional teachings about healing, speaking in tongues, and deliverance from demons. MacNutt possessed a unique ability to bridge the gap between Christian groups and became a beloved speaker in both Catholic and Protestant circles.

MacNutt first prayed for divine healing for a nun suffering the effects of shock treatment for depression. He reported that he had seen many healings “especially when I have prayed with a team or in a loving community.”

Affirming medicine, he wrote, “In no way do I conceive prayer for healing as a negation for the need for doctors, nurses, counselors, psychiatrists, or pharmacists. God works in all these ways to heal the sick; the ideal is a team effort to get the sick well by every possible means. . . .

“I am convinced through my own experience that prayer for healing brings into play forces far beyond what our own unaided humanity contributes. The results of prayer have been extraordinary—so much so that what once would have astonished our retreat team we now take almost for granted. The extraordinary has become ordinary.”

By Amy Collier Artman

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #142 in 2022]

Amy Collier Artman is on faculty in the religious studies department at Missouri State University and is the author of The Miracle Lady: Kathryn Kuhlman and the Transformation of Charismatic Christianity.Next articles

Healing power

How a pastor and a professor prayed for healing and started the third wave movement

Caleb MaskellHope, wholeness, healing

Two doctors discuss prayer and medical interventions working together to promote healing

John R. Peteet, John R. Knight Jr., and the editors