Fasts and feasts: FAQs

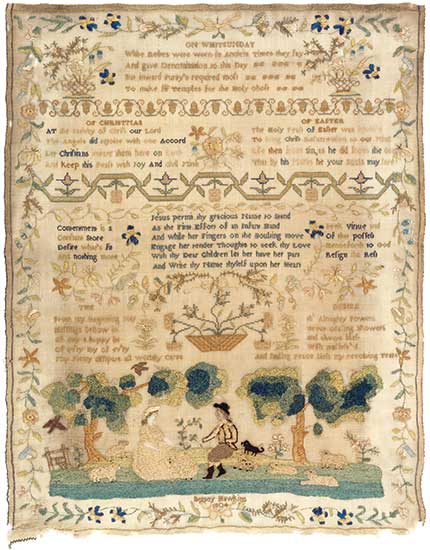

[ABOVE: Sampler of Liturgical Verses, 1804. Silk embroidery on wool. English—Public domain, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum Collection Textiles Department]

What is a “Christian” year?

The Christian year, sometimes called the “church year” or the “liturgical year,” is a historic calendar of fasts and feasts that has been celebrated in some form since the early church. It is organized around the life, death, and Resurrection of Jesus Christ.

Why do Christians celebrate fasts and feasts, anyway?

The Christian faith has always been deeply rooted in time. Christians believe that the Crucifixion and Resurrection really happened in human history, on a certain date and in a certain place. Christianity inherited from its Jewish background a history of celebrating (weekly) a Sabbath and (yearly) the important anniversaries of God’s mighty acts; some Christian festivals have a connection to Jewish counterparts (see pp. 4–5). The Bible makes clear in verses such as Isaiah 1:14 and Colossians 2:16 that keeping festivals is not a substitute for a transformed heart, but historically many Christian believers have found the daily, weekly, and yearly marking of time an aid to transforming the hearts of their community.

Which fasts and feasts developed first?

The earliest evidence for Christians explicitly marking time in honor of Christ is that they gathered weekly in celebration of the Resurrection. This pause in the week to honor Christ also drew on the history of the Jewish Sabbath. Christians also kept the Jewish practice of marking time by starting each new day at sundown the preceding evening. Christmas Eve and, believe it or not, Halloween are the most common occurrences of this practice today (“Hallowe’en,” as it’s more properly spelled, comes from “All Hallows’ Eve,” the day before All Saints’ Day, see p. 41); but in fact every feast day is considered to start on its preceding eve.

Meeting to worship on the “Lord’s Day” is attested in the New Testament itself (1 Cor. 16:2; Acts 20:7, 11; Rev. 1:10), as well as in early Christian writings, such as the early second-century Didache, which orders believers: “Every Lord’s day gather yourselves together, and break bread, and give thanksgiving after having confessed your transgression.” The Didache also commended twice-weekly fasting. The governor of Bithynia, Pliny the Younger, stated around 111 that the Christians he was trying to persecute “were accustomed to meet on a fixed day before dawn and sing responsively a hymn to Christ as to a god.”

So, after this weekly rhythm developed, how did we get the Christian year?

The Christian year developed backward from its major feasts. First and foremost was Easter, also called Pascha. By the fourth century, the penitential period of Lent and the remembrance of Christ’s Passion during Holy Week were added before Easter as preparations for the great Paschal celebration. The next feast most important to the early Christians was Pentecost, 50 days after Easter Day, which took its name from the Jewish feast—on that day the Holy Spirit first fell on the disciples (Acts 2:1–41); it originally commemorated both the descent of the Spirit and Christ’s Ascension (Acts 1:1–10) until Ascension moved backward and claimed its own day.

The other major early Christian feast may surprise you; it was not Christmas but Epiphany (January 6). Christians originally honored a number of events on this day: Christ’s birth, the visit of the Magi, Christ’s baptism, his first miracle, and the general manifestation of his glory to the Gentiles. Around the fourth century in the West, the celebration of Jesus’s birth moved backward to December 25, and eventually 12 days of Christmas took shape between then and Epiphany. By the fifth century, some Christians had begun observing a time of Lenten-like preparation before Christmas, which eventually developed into Advent as we know it today.

So, why does the date of Easter move around if Christmas and Epiphany don’t?

We’ll get into that on page 33.

How do saints fit into this?

Everything just mentioned is called the “temporal” cycle—the weekly and yearly remembrance of Christ’s mighty acts of salvation. Alongside this runs a “sanctoral” cycle—a yearly cycle of remembering saints. Beginning in the early second century and picking up steam after Christianity became legalized in the fourth, Christians began to remember local heroes, especially martyrs, on the anniversary of their deaths. (The first saint for whom we have a record of this is Polycarp—see CH #156.)

The longer Christianity endured, the more heroes and martyrs accumulated to remember, and eventually, by the twelfth century, a process whereby the pope could supervise the naming of saints for the entire Western church was established. (The process in Eastern Orthodoxy remains different and more localized.) Liturgical reformers for over a millennium have complained that the sanctoral cycle is in danger of overwhelming the temporal cycle, and various efforts to prune it back have been attempted. (Read more on pp. 46–49.)

When does the Christian year begin?

It took a while for this to be established—at least in some places the early church celebrated the Christian new year on Epiphany—but Advent is now considered the beginning of the Christian year.

Are there Scripture readings associated with these fasts and feasts?

Yes—historically, the church set Scripture readings for all Sundays and feast days in the Christian year. The technical term for a list of prescribed Scripture readings is “lectionary.” Christians read from the Old Testament and from the books that became the New Testament in worship from the faith’s earliest days; we begin to have strong evidence for various schedules of readings from about the fourth century. Today, Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox each have their own lectionaries. Many, but by no means all, Protestant denominations use a common schedule called the “Revised Common Lectionary” (RCL). Modern Western lectionaries generally operate on a three-year cycle that moves through most biblical books over the course of those three years.

What about colors?

Over the centuries many colors have been associated with decorations and vestments during certain seasons. In modern Western churches (and in this guide’s borders), blue and purple are usually used for Advent, white and gold for Christmas, green for Epiphany, purple for Ash Wednesday and Lent, deep red for Holy Week with black on Good Friday, white and gold for Easter, red for Pentecost, and green for Ordinary Time (for more on Ordinary Time, see pp. 18–19 and 42–44). Some colors are also associated with certain feasts or events throughout the year (white for All Saints’ Day and red for ordinations, for example).

Who celebrates the Christian year, and who doesn’t?

Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, Anglicans, and Lutherans celebrate the Christian year pretty much the way it is laid out in this guide. (While the overall structure is similar in Eastern Orthodoxy, significant differences have developed in when events are observed; see p. 45.) Most Protestant mainline denominations have retained or adopted at least some of the Christian year (especially colors, readings, and major feasts). Nondenominational, Holiness, and Pentecostal churches, except for celebrations of Christmas and Easter, generally do not mark many of these yearly feasts. Many have evolved an alternate structure focused around secular and civic holidays. Most Quakers officially celebrate no sacraments, organized worship, or holy days at all (see CH #117 for more). CH

By the editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #156+ in 2025]

Next articles

Jewish fasts and feasts

Christian fasts and feasts developed against the background of Jewish practices

Jennifer Woodruff TaitAwaiting his coming

Advent preparation spans the four Sundays before Christmas

Jennifer Woodruff TaitCelebrating Christ’s birth

The name “Christmas” is a shortening of “Christ’s Mass” in Middle English

Jennifer Woodruff TaitTwelve days of Christmas

Prolonged celebrations are supposed to start on Christmas day.

Jennifer Woodruff Tait