Jewish fasts and feasts

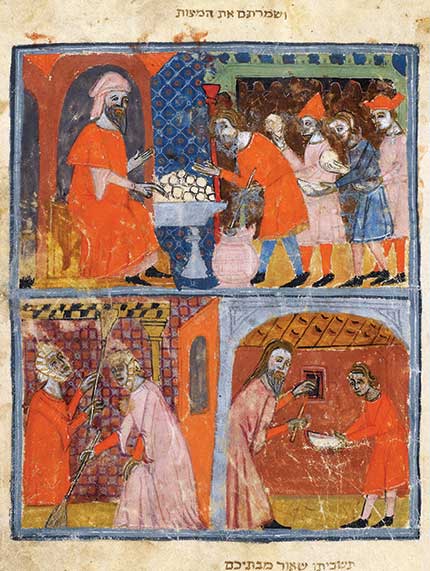

[ABOVE: Preparation for the Passover in Haggadah Pesach, Sister Haggadah, Or. 2884, f.17. Catalonia, mid 14th century—From the British Library archive / Bridgeman Images]

Christian fasts and feasts developed against the background of Jewish practices, and the following Jewish holidays existed at the time of Jesus and the early church. While modern Jews celebrate these holidays, their observances are not monolithic and the holidays have developed in varied and complex ways from the biblical period. Other observances have been added to the Jewish liturgical calendar since the time of Jesus. (To better understand holidays not discussed here and modern customs around these holidays from a Jewish perspective, see My Jewish Learning.)

In the Torah

The most important Jewish holidays are those in the Torah (the first five books of the Hebrew Bible), especially Leviticus 23 and Deuteronomy 16. (The dates are all officially set according to the Hebrew calendar, but we will use the Gregorian equivalents here for easier understanding.) Shabbat, the Sabbath, forms the foundation of the whole Jewish liturgical cycle. This weekly celebration is observed from sundown Friday to sundown Saturday; its observance is repeatedly commanded and ultimately traces back to the creation story in which God rests on the seventh day.

The Jewish New Year begins with the High Holy Days—Rosh Hashanah (which means literally “head of the year” or “new year”) and Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement). While the Torah mentions these observances, the names came later. They are preceded by a period of repentance that begins 40 days before Yom Kippur, and the 10 days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur are called the Ten Days of Repentance. The High Holy Days normally occur in September or October.

The Torah also refers to three pilgrimage festivals: Passover, or Pesach, commemorating the Hebrew people’s Exodus from Egypt (March or April); Shavuot, which celebrates the first grain harvest and the giving of the Torah to Moses on Mt. Sinai (May or June); and Sukkot, an autumn festival five days after Yom Kippur that commemorates the wandering in the wilderness (September or October).

Before the Second Temple’s destruction in Jerusalem in 70 AD, devout Jews would have gone on pilgrimage there for all three of these feasts. After its destruction home-based observances developed, including Passover seders and the building of a sukkah, or hut, for Shavuot. Scholars debate whether the Last Supper was a ritual Passover meal; if it was we do not know how closely it resembled the formal seders that developed later.

Other early feasts

Two festivals commemorate events in the Second Temple period (lasting from the time of the Jewish return from exile in the sixth century to the destruction of the Second Temple—the First Temple had been destroyed at the time of the exile in 586 BC.) The first festival, Purim (March), commemorates events described in the book of Esther—how, while the Jews were in exile in Persia, the Jewish Esther became queen of Persia and saved her people from genocide.

The second is Hanukkah (December), which remembers a story from the apocryphal book of 1 Maccabees—how Judah the Maccabee led a revolt against King Antiochus IV Epiphanes of the Seleucid Empire beginning in 167 BC and recaptured and rededicated the temple in Jerusalem in 164. While Hanukkah began as a fairly minor Jewish feast, it has grown in prominence over the years as a celebration and assertion of Jewish identity countering the Christmas season.

Fasting

Yom Kippur is the most famous fast day in the Jewish liturgical calendar, but observant Jews fast at many other times. In Hebrew history spontaneous fasts were often proclaimed to commemorate, pray for, or atone for a particular person or event. Eventually a calendar was developed called the Megillat Ta’anit, or Scroll of Fasts, that listed all the days on which one should not fast. The other major fast day in Jewish tradition besides Yom Kippur is Tisha B’Av, a day of communal mourning; it postdates the time of Jesus since it was first observed after the Second Temple’s destruction. It commemorates both the First and Second Temple destructions as well as other catastrophes that have beset the Jewish people since 70, such as the Crusades, the Holocaust (Shoah), and more local persecutions and disasters.

The Christian calendar

Early Christians deeply connected their practices of sacred time to Jewish conceptions. They understood liturgical time as a week punctuated by a Sabbath and a year marked by certain holy days. They observed holidays at sundown the night before and maintained an intentional rhythm of fasting and feasting—including the possibility of both spontaneous fasts and times when fasting was forbidden.

As far as specific holidays, events surrounding Jesus’s death and Resurrection are obviously tied to Passover/Pesach. Early Christians seized on symbolic resonances between the story of the Exodus and the freedom bought by Christ. Jerusalem was celebrating Shavuot (the Feast of Weeks, 50 days after Passover) when the Holy Spirit came in Acts 2:1–31; as the Greek word for “fiftieth” is pentecost, this was sometimes used in Greek-speaking contexts to denote Shavuot, but it has never been a common Jewish name for the feast. For more on Easter and Pentecost connections to Pesach and Shavuot, see pages 32–35; 36-37; 38-39. CH

By Jennifer Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #156+ in 2025]

Jennifer Woodruff Tait is Senior Editor of CH magazineNext articles

Awaiting his coming

Advent preparation spans the four Sundays before Christmas

Jennifer Woodruff TaitCelebrating Christ’s birth

The name “Christmas” is a shortening of “Christ’s Mass” in Middle English

Jennifer Woodruff TaitTwelve days of Christmas

Prolonged celebrations are supposed to start on Christmas day.

Jennifer Woodruff Tait