Heaven under our Feet

HENRY DAVID THOREAU (1817–1862) arrived on the shores of Walden Pond in 1845, fresh from his father’s pencil factory. On land owned by his friend and mentor, well-known writer and ex-minister Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882), Thoreau built a 10-by-15 foot cabin. His inventory of materials includes “one thousand old brick: $4.00,” “two second-hand windows with glass: $2.43,” and “Hair: $0.31. More than I needed,” plus other items for a grand total of $28.12. He furnished it with a bed, a table, a desk, a lamp, and “three chairs … one for solitude, two for friendship, three for society.”

For two years, two months, and two days Thoreau walked around the woods and into town (to drop off his laundry), entertained visitors in his three chairs, read, and kept a journal. He even got arrested for refusing to pay a poll tax as a protest against slavery. Seven years later his observations became the book Walden (1854). Perhaps no book better encapsulates the way many Americans felt about nature in the nineteenth century.

Thoreau and Emerson were part of a larger movement known as Transcendentalism, which sprung from the Unitarian movement among New England Congregationalists. Unitarians rejected the Trinity (their Uni means “one”) and emphasized human achievement instead of the doctrine of total depravity. They read English and German philosophy and Romantic poetry—especially William Wordsworth (1770–1850), whose works became the rage in the United States from the 1820s on, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834).

Romanticism famously exalted both nature and human imagination. Transcendentalists agreed. They thought conformity plagued America’s continent-conquering culture, and they disliked its booming new technologies: steamboats, railroads, telegraphs. Emerson wrote: “Cities give not the human senses room enough. We go out daily and nightly to feed the eyes on the horizon, and require so much scope, just as we need water for our bath.”

Eventually some Transcendentalists—including Bronson Alcott (1799–1888), father of Louisa May Alcott (1832–1888), author of Little Women—established utopian communities to live together in harmony with nature. Most failed; Alcott satirized her father’s effort in Transcendental Wild Oats (1873).

Many Transcendentalists sought the divine in outdoor experiments; most rejected traditional churches and doctrines to do so. Thoreau eventually left Christianity altogether, not least because he saw Christians as supporting slavery. Yet he wrote in his journals, “My profession is always to be on the alert to find God in Nature, to know his lurking-places, to attend all the oratorios, the operas, of nature”; and in Walden, “Heaven is under our feet as well as over our heads.”

Order Christian History #119: The Wonder of Creation in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

This article is from Christian History magazine #119 The Wonder of Creation. Read it in context here!

By Jennifer Woodruff Tait

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #119 in 2016]

Jennifer Woodruff Tait, managing editor, Christian HistoryNext articles

Cosmic worship, sanctified matter, transfigured vision

Christian poets, mystics, priests, and preachers encourage us to worship God by experiencing his creation

Kathleen A. MulhernThe heavens declare the glory of God

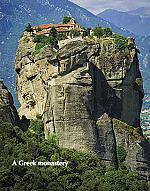

Monks and nuns left us a legacy of spirituality honoring God’s creation

Glenn E. MyersAll life has its roots in me

Hildegard personifies the fire of God’s Spirit in this excerpt from her Book of Divine Works

Hildegard of Bingen