“Jack took care of me”

[C. S. Lewis standing with David and Douglas Gresham, September 1957, GR55-1. Used by permission of the Marion E. Wade Center, Wheaton College, Wheaton, IL]

Marjorie Lamp Mead: You have described the first time that you met C. S. Lewis often (both in books and in talks), but many have still not heard this story. Could you please share your memories of meeting Jack for the first time? What had your mother told you and David before you met him?

Douglas Gresham: When I first arrived in England, I found it to be a grubby, sooty, and smoky place and was not particularly impressed. We lived in a small offset house which was part of a cheap hotel. I listened intently as Mommy read more of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, because the next day she was going to take us up to Oxford to meet her friend, and we were to stay for a while in the freezing cold of Oxfordshire in winter.

I first met him as “Jack,” not

C. S. Lewis, as Jack was his chosen nickname. He took it for himself when he was about four years old from a little dog that he was fond of in the village close to where his family lived. The little dog, “Jacksie,” was accidentally killed one day so Jack took his name to himself and it lasted all his life.

I was eight years old when Jack invited my mother (with his brother Warnie’s happy consent) to bring her boys and spend a few days at his home, “The Kilns.” I had heard quite a lot about this amazing man, whom I had seen in my mind to be tall, handsome, strong, and probably wearing silver armor. My brother and I arrived at The Kilns, and my mother ushered us in through the back door and into the kitchen. There, standing in the doorway that would lead to the middle of that lovely house, was the strangest looking man I had ever seen! Remember that I was a little American boy who had never seen anyone who was dressed as shabbily as Jack was dressed that day. His baggy gray trousers were scattered with cigarette ash; his shoes (though one could hardly have called them that) were slide-on slippers, the heels of which were crushed; and his jacket was in total shambles, torn holes in the elbows and other tears here and there. His shirt, though, was clean, and the collar of it spread out over the lapels of the jacket.

Initially I was taken aback and beginning to worry about what our Mommy had gotten us into. And then Jack started to talk. His whole face became a smile and he said “Hello, hello, hello! Welcome, welcome!” His speech, and his eyes glowing with joy, suddenly changed him from a shabby scarecrow into a vibrant and friendly man glowing with wisdom and happiness. Warnie was a bit behind Jack, and equally, he too immediately made me smile. I very soon learned to like Jack and later on to love him dearly. Now I miss him all the time.

MLM: How did your sense of Jack change over time—or did it?

DG: My sense of who and what Jack was never really changed much at all, but it grew steadily over the days and then the weeks and then the months as we started getting to know him; first, while we lived in London, then later when we moved to Headington (just about 30 miles east of the middle of Oxford). My brother and I eventually moved to The Kilns as Mother was dying. I had seen much more of Jack when we moved to Headington than I had when we lived in London, and he and Warnie together made me greatly welcome at The Kilns. I could ride my bike from Headington to The Kilns and then play in the woods and lake near The Kilns, and also in the air raid shelter that the gardener, Fred Paxford, and Jack had built during World War II, long before I got there. This air raid shelter became my personal place to haunt and play in.

Jack didn’t really change much at all as far as I was concerned, he just became steadily more and more of himself. But Jack was changing in one important way, though not to me directly. He slowly but steadily grew emotionally closer to my mother than he had been. And indeed they were married when she was thought to be dying. I, in the meanwhile, grew closer to Jack and to a lesser degree to Warnie as well. Jack was a pure man, a kind, gentle, and loving man, and all of those qualities were increasingly evident as I grew to know him better.

MLM: What are the most important things that you learned from your stepfather? In other words, how has he influenced you?

DG: First and foremost I learned to love, which perhaps was the most important lesson of all. I learned the almost unbelievable power and joy attached to reading good books. As a result I am what I am today all these years later, still living under the warm glow of Jack’s love and gentle instruction. When Mother died he and I wept together for a long time at first and then in lesser times later. I learned also, contrary to what English schools tried to teach me, that there is no shame in weeping for loved ones. From Jack I learned the great value to be found in helping others, that helping other people not only rewards those being helped but even more, helps the person doing the helping. I learned from Jack as well as my mother, and some from Warnie, though it took me a good while to realize it; without what they left in me, I would be a much lesser person than I am.

MLM: What would you like people to understand most about your stepfather?

DG: To stop trying to pretend that he was less than he really was, to stop issuing false sayings and claiming them to be from Jack. I want people to say nothing about Jack till they take the trouble to find out what kind of a man he really was. We have had numerous bad biographies of Jack’s life and a very few really good ones. Ditch the ones that are trying to show off the authors themselves, and instead read the ones that show Jack for what he was. Preferably those by authors who knew Jack very well, such as one of the first and still the best one available—Jack (1988), written by one of Jack’s best friends, George Sayer, and yet pulling no punches even though he wrote about his friend.

MLM: How did your mother change Jack? How did Jack change your mother?

DG: Both of them changed each other and for the better. You see these were two very remarkable people, both of them carrying huge intellects, and when you put the two together, wondrous and amazing things happened. Perhaps the best illustration of this would be Till We Have Faces, a book carefully written by both Jack and Joy together—Jack actually wanted to have it published under both their names, but Mother said he was not to do so and he relented—and written so that the female characters emerge as very real women (both good and bad). I may well be the only person left in the world who watched them and heard them working out that very powerful

tale together.

Mother changed Jack in other ways as well, and Jack likewise changed Mother too, and all of these changes were for the good. Examples are simple, such as Mother insisting on renovating The Kilns. That house was not-so-slowly falling apart till she had it all repaired and repainted. It was a very much better home to live in afterward.

Jack changed my mother by the simple fact of loving her. Loving her when she was strong and agile and continuing to love her (if not loving her even more) when she was physically being eaten alive by her cancers. Jack would work harder than ever before to find time to be with her as often as he could, and she likewise would do whatever she could to help Jack in his work. The two of them changed each other and thank God, they also

changed me.

MLM: Almost since your very first visit to the Wade Center in 1982, you have dedicated your working life to preserving your stepfather’s legacy. What helped you decide to do this? What has it meant to you to be able to be a steward of Jack’s legacy? What have you enjoyed the most about this?

DG: The answer to that is simple. Jack took care of me so I will as best I can, take care of him—even if he is dead. What helps me to do that work is that he deserved the very best that I can do for him. Jack sat at my mother’s bedside and his love for her was evident; well, I loved her too and grew to love him.

One of the best parts about looking after Jack’s works, as best I can, is that many people attend C. S. Lewis symposia and such, and they make me very welcome. People ask me about Jack, and I am always happy to tell them. As for Jack’s legacy, I am the only person still living who lived with both Jack and Warnie, and the only one still alive who is able to tell folks about them. Much better to let others know what kind of wonderful people they both were. Warnie was a fine man till his alcoholism took him. Jack’s death left Warnie alone, and he simply could not stand that loneliness. I still grieve now and then for both of them. Why should I want to hide all their goodness away inside myself? CH

By Douglas Gresham and Marjorie Lamp Mead

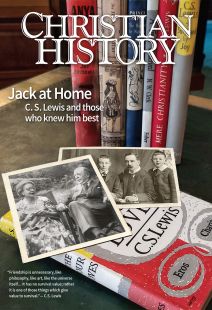

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #140 in 2021]

Marjorie Lamp Mead, associate director of the Marion E. Wade Center, has been friends with Doug Gresham since they first met in 1982. She spoke with him on behalf of Christian History.Next articles

Questions for reflection: Jack at home

Questions to help you think more deeply about this issue.

the editorsJack at home: recommended resources

With scores of books by and about C. S. Lewis—where to begin? Here are suggestions compiled by our editors, contributors, and the Wade Center.

the editors"Something profound had touched my mind and heart”

Some of Lewis’s scholarly colleagues and those who carried on his legacy

Jennifer A. BoardmanCity of Man: Did you know?

What is civic engagement? Church leaders have long reflected on how Christians should live in the world

The editors