Learning to see

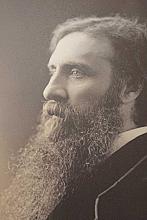

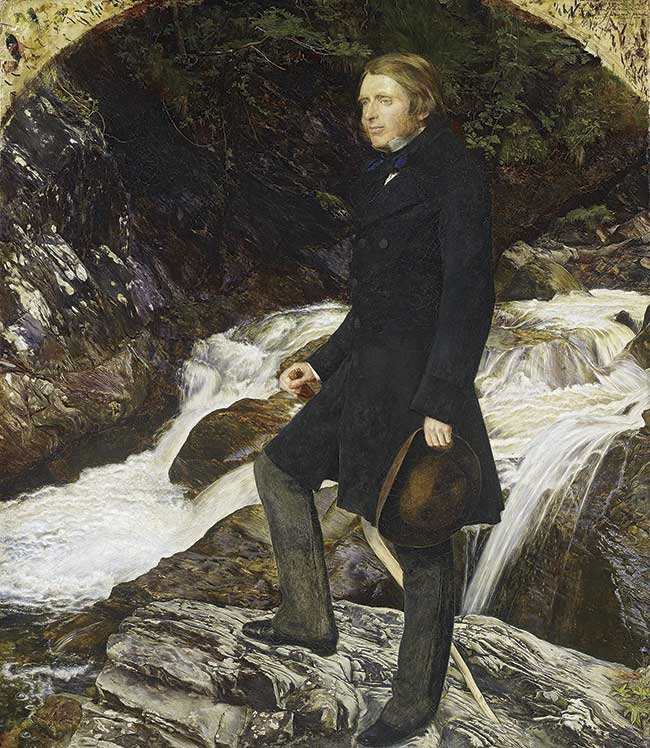

[John Everett Millais, John Ruskin, 1854. Oil on Canvas—© Ashmolean Museum / Bridgeman Images]

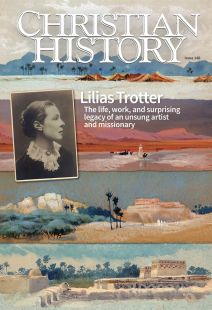

One of Lilias Trotter’s final projects was to leave English readers a portrait, in vivid watercolors and word-painting, of her beloved Algiers: “The colour pages and the letterpress,” she wrote in the Preface to Between the Desert and the Sea (1929), “are with one and the same intent—to make you see. Many things begin with seeing in this world of ours.”

It was a lesson she had learned decades earlier from her mentor, John Ruskin, who argued in his monumental work Modern Painters (five volumes, 1843–1860):

The greatest thing a human soul ever does in this world is to see something and tell what it saw in a plain way. Hundreds of people can talk for one who can think, but thousands can think for one who can see.

For this man who more than anyone else shaped the aesthetic landscape of his generation, to see clearly—and to help others to see—was a profoundly moral, and indeed Christian, vocation.

Art is praise

But as the century wore on, a widespread cultural crisis of faith, infecting even Ruskin himself, began undermining the idea that truth and beauty, faith and art, had anything to do with each other.

Before the Victorian period, being a painter in England typically meant a life of poverty as a lower-class artisan. The vocation of an artist was not quite socially respectable and certainly not a gentleman’s profession. But through his writing, which transformed the cultural conversation around art, and his efforts to educate public taste, Ruskin elevated the role of the artist to that of visionary and prophet—someone who sees and delights in the deeper truths symbolized in nature and is able, through careful observation and faithful representation, to convey those truths to others.

Modern Painters offered readers a startling new perspective on the world of art. Ruskin argued for the superiority of modern landscape painters—and particular J. M. W. Turner (1775–1851)—over the “Old Masters” of the post-Renaissance period who failed in their attention to the objective, divinely created facts of nature. He scorned the method of composing idealized landscapes in the studio rather than, like Turner, personally engaging with the “truths” of water, air, clouds, stones, and vegetation. Suspicious of subjectivism, Ruskin sought to ground the definition of beauty in the eternal character of the Creator. Having good aesthetic taste is a moral virtue, according to Ruskin; we have a duty to love that which is truly beautiful and which elevates humanity, and to turn away from the ugly and undeserving.

Likewise an artist has a moral purpose in society, and that purpose is not primarily fulfilled by painting didactic or religious subjects. The pure-hearted artist witnesses to God’s glory as manifest in the beauty of creation; therefore, Ruskin wrote, “All great art is praise.”

The beauty of the real

The radical nature of Ruskin’s emphasis on accuracy and authenticity can be seen in the controversy surrounding Christ in the House of His Parents (1850) by a young John Everett Millais (1829–1896), member of the newly formed Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Unlike those who had depicted idealized biblical narratives in the past, Millais painted a dirty rustic setting (based on an actual carpenter’s shop) and ordinary-looking characters with a “vulgar” realism that shocked and scandalized the public. Charles Dickens famously scoffed that Millais’s Christ was

a hideous, wry-necked, blubbering, red-haired boy in a nightgown, who appears to have received a poke playing in an adjacent gutter, and to be holding it up for the contemplation of a kneeling woman, so horrible in her ugliness that . . . she would stand out from the rest of the company as a monster in the vilest cabaret in France or in the lowest gin-shop in England.

But Ruskin sprang to the defense of Millais: “Pre-Raphaelitism has but one principle, that of absolute, uncompromising truth in all that it does, obtained by working everything, down to the most minute detail, from nature, and from nature only.” Comparing them to medieval artists driven by Christian principles, he argued that supporting such a “noble school” of artists was the morally right thing:

The best patronage of art is not that which seeks for the pleasures of sentiment in a vague ideality, nor for beauty of form in a marble image; but that which educates your children into living heroes, and binds down the flights and the fondnesses of the heart into practical duty and faithful devotion.

The great art critic’s support propelled the Pre-Raphaelites to fame, and works such as William Holman Hunt’s (1827–1910) The Light of the World (c. 1854) and The Awakening Conscience (1853) resonated with the evangelical spirit of midcentury Victorian society. Ruskin’s emphasis on painting from real-life observation—combined with the new cultural fascination with historical and archaeological study of the Bible—prompted Hunt and others to travel to the Holy Land to capture the biblical landscape more accurately and, in Hunt’s words, “to make more tangible Jesus Christ’s history and teaching.”

Ironically, Ruskin’s belief that aesthetic style, not just subject matter, carried moral weight later led him to revile the most popular biblical illustrator of the late 1860s and 1870s, Gustave Doré (1832–1883). The French artist became a celebrity in England with his dramatic (though often inaccurate) portrayals of London’s urban underbelly and his wood-engravings for Paradise Lost, The Divine Comedy, and the Bible. The Doré gallery in London was a place (in the words of one contemporary) “where the godly take their children.”

It appalled Ruskin, however, and he saw in Doré’s immense popularity the consummate sign that public taste was rapidly devolving from his own ideals. “You are all wild,” he complained, “with admiration of Gustave Doré. Well, suppose I were to tell you . . . that Gustave Doré’s art was bad—bad, not in weakness,—not in failure,—but bad with dreadful power—the power of the Furies and the Harpies mingled, enraging, and polluting; that so long as you looked at it, no perception of pure or beautiful art was possible for you.”

Doré’s stylistic use of grotesque exaggeration, his “lewd” and “morbid” fascination with what Ruskin considered to be moral ugliness, was in the elder critic’s view the most crude and dangerous sensationalism; Doré’s illustrations may have been about true things, but according to Ruskin’s definition, they weren’t true.

Crisis of faith

Gustave Doré was the least of Ruskin’s problems in the latter half of the century. In addition to personal tragedy and mental illness, tumultuous cultural forces were shaking the very foundations on which Ruskin’s ideals were built.

Victorian evangelicalism—a very restrictive form of which had been Ruskin’s upbringing—became increasingly conflicted. Scientific advances, higher biblical criticism, and a pervading cultural ideal of materialistic rationalism began to complicate cherished tenets of popular British Christianity. Perhaps most damaging for Ruskin’s ideas about the beauty of Creation, science was changing people’s understanding of the relationship between God and nature. (For more on this, see CH 107, Debating Darwin.)

Even before Darwin the discovery of dinosaur bones and the publication of Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology (1830–1833) exposed a more brutal natural history than had ever been realized. Lyell’s evidence for Earth’s ancient past, including the mass extinction of entire species, was difficult for some to reconcile with a God who created and reveals himself through the natural world. Ruskin confided to a friend,

You speak of the flimsiness of your own faith. Mine, which was never strong, is being beaten into mere gold leaf. . . . If only the geologists would let me alone, I could do very well, but those dreadful Hammers! I hear the clink of them at the end of every cadence of the Bible verses.

In 1858 he experienced what he called a “deconversion” from the stern, dour religion of his upbringing. On a trip to Turin, Italy, the stark contrast between a local preacher’s sermon about damnation and the sight of Paolo Veronese’s sixteenth-century painting Solomon and the Queen of Sheba led him to conclude that the magnificent power of the irreligious artist’s gift had more truth and devotion in it than anything he had heard in church.

Like many of his contemporaries, Ruskin plunged into decades of agnosticism. But during these years, he maintained a close friendship with popular Christian writer and teacher George MacDonald (1824–1905), best known today for fantasy works such as Phantastes (1858) and “The Golden Key” (1867) and his influence on C. S. Lewis (see CH #113).

“The God of the beautiful”

MacDonald became Ruskin’s confidant during the latter’s ill-fated romance with Rose La Touche (1848–1875). In his theological openness, undaunted by doubts and questions, and in his gift for reenchanting the world with a sense of divine beauty and purpose, he served as something of a spiritual lifeboat for many who, like Ruskin, found themselves suddenly reeling with uncertainty and disillusionment (see p. 16). MacDonald’s own spiritual growth as a young man had been characterized by a dawning awareness of the “beauty of religion.” He explained to his father,

One of my greatest difficulties in consenting to think of religion was that I thought I should have to give up my beautiful thoughts and my love for the things God has made. But I find that the happiness springing from all things not in themselves sinful is much increased by religion. God is the God of the Beautiful, Religion the Love of the Beautiful, and Heaven the House of the Beautiful.

Beauty, MacDonald believed, is the Spirit of Truth shining through the forms of the world. In a lecture on Wordsworth’s poetry, he called God “the first of artists”:

Whatever we feel in the highest moments of truth shining through beauty, whatever comes to our souls as the power of life, is meant to be seen and felt by us, and to be regarded not as the work of his hand, but as the flowing forth of his heart, the flowing forth of his love for us, making us blessed in the union of his heart and ours.

The purpose of art, for MacDonald, is to give people a vision of the ideal, to awaken their imaginations and draw them to see, love, and follow the beautiful. Art is a means of knowing truth through beauty and, through love of beauty, becoming more true.

While their ideas about beauty and truth resonated deeply, MacDonald was able to hold on to a firm faith in God that Ruskin feared was slipping out of his grasp. When MacDonald sent him the first volume of his Unspoken Sermons, Ruskin responded, “They are the best sermons—beyond all compare—I have ever heard or read—and if ever sermons did good, these will. Pages 23–34 are very beautiful—unspeakably beautiful. If they were but true! . . . But I feel so strongly that it is only the image of your own mind that you see in the sky!” It is no wonder Ruskin was later drawn, not only to Trotter’s artistic talent and love for nature, but also to her deep faith. She, like MacDonald, believed in a vision of God that he desperately longed for—indeed, clung to—until, in his last years, he was finally able to return.

MacDonald on his part loved Modern Painters so much he gave it to his fiancée, Louisa, as an engagement gift, and he directly engaged Ruskin’s ideas in The Seaboard Parish, published in 1868 after five years when Ruskin had spent much time with the MacDonalds. Near the beginning the vicar’s daughter responds eagerly to an offer of art lessons:

“. . . For I have had no one to help me since I left school, except a book called Modern Painters, which I think has the most beautiful things in it I ever read, but which I lay down every now and then with a kind of despair, as if I never could do anything worth doing. How long the next volume is in coming! Do you know the author, Mr. Percivale?”

“I wish I did. He has given me much help. I do not say I can agree with everything he writes; but when I do not, I have such a respect for him that I always feel as if he must be right whether he seems to me to be right or not. And if he is severe, it is with the severity of love that will speak only the truth.”

Novelist Lucy B. Walford (1845–1915) attended a “house lecture” given by MacDonald in the home of an artist, and she was thrilled to spot “the great Ruskin” in attendance and hear the two have a lively discussion about the role of imagination in architecture and landscape painting.

Art for art’s sake

Meanwhile, during those years of spiritual crisis, the art world had begun to divide in two—on the one side, those schooled by Ruskin; on the other, those who caught the spirit of the Aesthetic movement of the 1870s, whose mantra was “art for art’s sake.” One of the leading figures in this movement, a brash, experimental painter named James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), argued, “Art should be independent of all clap-trap—should stand alone, and appeal to the artistic sense of eye or ear, without confounding this with emotions entirely foreign to it, as devotion, pity, love, patriotism, and the like.”

When Ruskin harshly ridiculed one of Whistler’s paintings, sneering that he “never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face,” Whistler sued the famous art critic for libel—and won (though the court awarded him only a farthing, a quarter of a penny, in damages).

The notorious lawsuit stirred up an acrimonious debate about artistic philosophies and the nature of art criticism and seemed to seal (in his own mind at least) the end of Ruskin’s influence. From that point the idea that beauty is grounded in objective divine truths, or that art should have a moral purpose in society, was seen as increasingly outmoded. An 1893 article in The Studio Magazine described the newer generation of art critics:

They have burned their ships. They have closed their Ruskins forever. They have chosen their own gods—gods whom their fathers never admitted even within the gates. Our Philistine, on the other hand, bears upon his shoulders the weight of a wagon-load of Ruskinian and other theories. Art to him must still be beautiful, spiritual, an incentive to holy living.

The great engine of the modern art world was speeding away from him, yet the “philistine” views of Ruskin persisted in hidden corners—such as Algiers, where a missionary-painter lived out her mentor’s ideals in ways he’d never dreamed: teaching people to see. CH

By Kirstin Jeffrey Johnson & Jennifer Trafton

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #148 in 2023]

Jennifer Trafton is the author of a forthcoming book on Lilias Trotter with B & H Publishing, slated for fall 2024. Kirstin Jeffrey Johnson is a George MacDonald scholar who writes and lectures internationally on MacDonald, the nineteenth century, the Inklings, and faith and the arts.Next articles

Minds occupied with heaven

Organizing laypeople for piety and service in the Nineteenth Century

Kevin BelmonteChristian History Timeline: Lilias Trotter

A life of art and service. Trotter’s experiences amid the cultural and missional currents of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries

the editors