Minds occupied with heaven

[Edward Clifford, A group portrait of The Broadlands Conference, 1887. Pencil, watercolour and bodycolour—Dreweatts 1759 Ltd]

Is it our souls’ hunger and thirst that, before He comes, we may have given every message He had for us to deliver—prevailed in every intercession to which He summoned us—“distributed” for His kingdom and “the necessity of saints” every shilling He wanted . . . poured out His love and sympathy and help as He poured them out on earth?

Lilias Trotter, Parables of the Christ-life (1899)

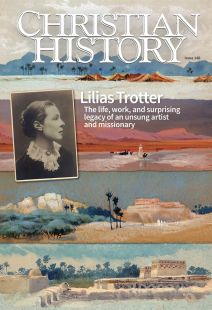

In May 1928, during the last summer of her life, Lilias Trotter lay confined to her bed in Dar Naama. But the 74-year old woman was still very much alive, vibrantly holding a Sunday afternoon Bible study for members of the Algiers Mission Band (AMB) and visitors. Normally this was the job of the chaplains, but as they were all on vacation, she pitched in as always, explaining the beauty and the spiritual meaning of the carvings in Solomon’s temple.

Back in 1874, at age 21, Trotter had sat with her mother among 98 other invited guests at a six-day “higher life” convention at Broadlands. There, in the estate’s park, she heard Hannah Whitall Smith expound the Bible, teaching “entire surrender to the Lord, and a perfect trust in him” (as Smith would later write in The Christian’s Secret of a Happy Life).

How could the 21-year-old Trotter know that one day she would fill Smith’s place as a bearer of the gospel to people hungry for its truth? Yet as Trotter strove throughout her life to make entire surrender to the Lord, she carried the lessons she had learned at Broadlands and in all the other places she had prayed, worked, and trusted in the Victorian evangelical world.

“Winds of heaven swept the land”

The conference at Broadlands was the beginning, not the end, for Trotter. She would soon encounter American evangelist D. L. Moody (1837–1899). A herald of the faith, Moody had, since the late 1850s, been a prime mover in the YMCA in Chicago and one of the most visible leaders of all its programs: lodgings, lectures, lending libraries, gospel gatherings. He directed the YMCA’s work at its headquarters at Farwell Hall. Moody’s transatlantic ministry as a lay preacher began there, providing him some of his first opportunities to speak publicly about things of faith.

Fast forward to 1875; gospel gatherings led by Moody and his famous song leader, Ira Sankey (1840–1908), took London by benevolent storm. And Trotter was there. One of her biographers, I. R. Govan Stewart, noted:

Lilias and her sister Margaret first attended the meetings at the Royal Opera House in the West End, the second of the four great missions in London which covered a period of four months, from March to July, 1875. They were invited to join the choir and met for practices at the home of [Lord and Lady Kinnaird], at 2 Pall Mall East, where Sankey was staying. Those were wonderful days, when the winds of heaven swept the land. …

During this particular mission to Great Britain, Moody preached to millions over a stay that extended from June 1873 to July 1875. (He would return in the 1880s.) The resulting movement for spiritual renewal became internationally famous and reached its zenith between March 9 and July 21, 1875, when, rotating between four spots—Agricultural Hall, Islington; the Royal Opera House, Haymarket; Camberwell Green; and Bow Common—Moody addressed more than two and a half million people.

This set the stage for similar gospel gatherings in America, also drawing great numbers in 1876. During that year President Ulysses S. Grant came to hear Moody preach to a crowd of thousands in Philadelphia.

“Divine compassion”

After her spiritual experience at the Moody-Sankey gathering in London, Lilias Trotter sought to bring, as Stewart put it, “divine compassion” to others: the hope of salvation, yes, but hand in glove with this, an abiding commitment to the less fortunate in England. This led very naturally to her involvement with the Young Women’s Christian Association, a group Moody ardently supported in his gatherings.

By this time the YWCA and its precursors had been in action for about two decades. A notice from the May 1857 issue of The Wesleyan-Methodist Magazine caught the spirit of the newly fledged enterprise:

YOUNG WOMEN’S CHRISTIAN ASSOCIATION,

35, NEW BRIDGESTREET.

This Association (established a few months since) is under the presidency of Lord and Lady Shaftesbury. Among its Vice-Presidents are several Clergymen of the Church of England, and of other denominations. Its object is to furnish suitable means for the social, mental, and spiritual elevation of the young women of the metropolis; and the plan pursued is similar to that of the Young Men’s Christian Association, Aldersgate-street.

The following are among the advantages offered:

1. A spacious and comfortable reading room.

2. Bible-classes.

3. Singing-classes.

4. Lectures.

5. Classes for mental improvement.

6. Library.

7. A register office will shortly be open for the benefit of those who give, and of those who seek, employment.

The YWCA in England, from its inception, saw both spiritual formation and what became known as the “social gospel”—philanthropic relief work—as both indispensable concerns. Faith was the fountainhead and guiding inspiration for charitable work. The YWCA never sought to have one without the other. With these twin pillars, the association became an international phenomenon: by 1900, hundreds existed in the United States.

Another facet of nineteenth-century faith highly influential in the life of Trotter was tied to England’s famous Lake District. Mention Keswick, and a host of storied images gather in the mind’s eye: a beautiful region of England and also a word synonymous with rest, renewal, and spiritual reflection. The Keswick Convention’s cofounder and guiding light was Thomas Dundas Harford-Battersby (1823–1883), canon of St. John’s Church, Keswick. Harford-Battersby’s father, John Harford of Blaise Castle in Bristol, was a biographer and close friend of previous evangelical reformers such as William Wilberforce (1759–1833) and Hannah More (1745–1833). Harford-Battersby’s great desire was to keep and “maintain the Christ-life.”

In concert with a Quaker friend, Robert Wilson, who would later mentor Amy Carmichael (see p. 29), he arranged for the first Keswick Convention to be held in a tent on the lawn of St. John’s vicarage. It started with a Monday evening prayer meeting in late June, which continued until the following Friday. Over 400 people united under the banner of “All One in Christ Jesus”—which remains the convention’s watchword today. Keswick Ministries reports the rest of the story:

Within a few years, Christians from all over the world were making an annual pilgrimage to the little Lake District town, to hear the best Bible teachers that were available. . . . After attending a conference in Oxford, Harford-Battersby commented: “Christ was revealed to me so powerfully and sweetly as the present Saviour in his all sufficiency.” And later he added “I found he was all I wanted: I shall never forget it.”. . . . It was to share this teaching more widely that the Convention was founded.

Not only was Trotter connected to the earliest meetings, but visits there on furlough from the mission field were a tonic for her soul—times when prayer, spiritual reflection, and the study of Scripture were, quite literally, a God-send. The Missionary Review of the World, in November 1898, painted a prose portrait of such Keswick moments:

The great gathering . . . is over, but the fragrance of it will long linger. . . . Every year the influence of Keswick teaching reaches out further. . . . And for this no one can fail to thank God who attends these conventions, and observes the sound scriptural teaching on holy living, and the simple, informal, spiritual worship of prayer, praise, and Bible study. . . . [It is] unique and exceptional.

Like Trotter, Moody became a great friend and supporter of the Keswick Convention. Northfield, the small New England town that hosted Moody’s famous Summer Conferences starting in 1880, was many times called “the Keswick of New England.” And pastor and writer Delevan Pearson wrote in Northfield Echoes (1896): “Mr. Moody has . . . expressed the desire to make Northfield the American Keswick.”

Complementary streams

While the Moody-Sankey gospel gatherings, the origins of the YWCA, and the Keswick Convention were distinct movements, they all focused on three things:

1. proclamation of the gospel,

2. elevation of those in spiritual or physical need, and

3. consecration to a deeper Christian life.

The Moody-Sankey gatherings centered on what Moody called “the great invitation” to faith, the call to become a Christian. From its first days, the YWCA cared deeply for this also, stating in May 1857 that the “spiritual elevation” of young women in London was a cherished goal. And of course, the Keswick Convention, from its inception, was dedicated to “keep and maintain the Christ-life.”

To find, keep, and maintain the Christ-life; Lilias Trotter cherished all these. Indeed they were the heart of her missionary and philanthropic endeavors. We do well to mine the legacy discovered here: the legacy she knew, and kept. CH

By Kevin Belmonte

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #148 in 2023]

Kevin Belmonte is the author of numerous biographies of great Christians, including William Wilberforce and D. L. Moody: A Life.Next articles

Christian History Timeline: Lilias Trotter

A life of art and service. Trotter’s experiences amid the cultural and missional currents of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries

the editorsCooperation for the gospel

Trotter’s mission was part of the exploding nineteenth-century evangelization of North Africa

Rebecca C. PateGod told her to go

Like Trotter, Amy Carmichael blazed her own missionary trail

Jennifer Woodruff Tait