Leprosy

IN THE TWELFTH and thirteenth centuries a leprosy epidemic spread through Europe, and many leper houses were built. By 1225, there were somewhere in the neighborhood of 19,000 leper houses in Europe. Later, many of them served as hospitals for victims of the bubonic plague.

The decision on whether any given person had leprosy and should therefore be admitted to a leper house was usually made by a panel from the parish, consisting of both clergy and laity. Lepers from a nearby leper house would sometimes be included as well. The panel would study the physical symptoms, including checking for the presence of a red nose and face, skin rashes, and hoarseness, and then render one of three judgments: healthy, leper, or suspected leper (with examination to occur again in one year). In cases where the person protested the diagnosis, he or she would usually be examined again by a panel made up fully of lepers. According to historian Guenter Risse, these panels often had to take an oath to reach a fair judgment, keep no secrets, and not accept gifts or bribes. (Some applicants would do anything to avoid being placed in a leper house even if they were lepers; others found the idea of secure housing and food for the rest of their lives attractive.)

By The editors

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #101 in 2011]

Next articles

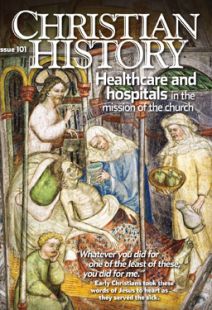

Editor's note: Health care

The church was more influential in the history of healthcare than you might expect

Chris ArmstrongA New Era in Roman Healthcare

How the early church transformed the Roman Empire’s treatment of its sick

Gary B. FerngrenFrom poorhouse to hospital

How the Christian hospital evolved from a house of charity that cared for the poor to the medical institution we know today

Timothy S. Miller