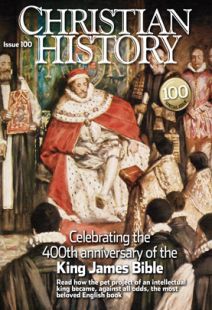

Master of language: Lancelot Andrewes

THE TOP TRANSLATOR and overseer of the KJV translation, Lancelot Andrewes was perhaps the most brilliant man of his age, and one of the most pious. A man of high ecclesiastical office during both Elizabeth’s and James’s reigns, bishop in three different cities under James, Andrewes is still highly enough regarded in the Church of England to merit his own minor feast on the church calendar.

Though Andrewes never wrote “literature,” modern writers as diverse as T. S. Eliot and Kurt Vonnegut Jr. have called him one of the great literary writers in English. His sermons feel too stiff and artificial and are clotted with too many Latin phrases to appeal to most today, but they are also filled with strikingly beautiful passages. Eliot, a great modern poet in his own right, took a section of an Andrewes sermon and started one of his own poems with it (“The Journey of the Magi”):

A cold coming we had of it,

Just the worst time of the year for a journey,

and such a long journey:

The ways deep and the weather sharp,

The very dead of winter.

Andrewes served not only as the leader of the First Westminster Company of Translators, which translated Genesis – 2 Kings, but also as general editor of the whole project. He very likely, as Benson Bobrick suggests, drafted the final form of “such celebrated passages as the Creation and Fall; Abraham and Isaac; the Exodus; David’s laments for Saul, Jonathan, and Absalom; and Elijah’s encounter with the ‘still small voice.’”

Born in 1555, Andrewes studied at Cambridge with Fairie Queene author Edmund Spenser. Early in his life he sympathized with the Puritan cause, but over time he soured on Calvinist dogma and turned to a more liturgical piety. In fact, he was to become one of Elizabeth’s “heavies,” interrogating Puritan separatists imprisoned deep in some of London’s foulest jails.

Ordained at 25, Andrewes worked his way up the ecclesiastical ladder to dean of Westminster and chaplain to Queen Elizabeth. Nicolson calls him “an ecclesiastical politician who in the Roman Church would have become a cardinal, perhaps even pope” as well as a minister who was “deeply engaged in pastoral care, generous, loving, in public bewitched by ceremony, in private troubled by persistent guilt and self-abasement.” He would wait every day, no matter how busy he was, in the transepts of his church “for any Londoner in need of solace or advice.”

It was for his linguistic mastery that Andrewes caught James’s eye as the perfect lead translator. After all, the man spoke 15 modern and 6 ancient languages! Andrewes also possessed a memory bordering on the photographic. So sought-after was he by scholars from around the world that Hugo Grotius, the great Dutch legal authority and historian, called meeting Andrewes “one of the special attractions of a visit to England.”

If this were not enough, however, Andrewes had quite possibly also saved his king’s life. His own consecration as Bishop of Chichester in the fateful November of 1603 delayed the start of Parliament by a day, thus helping to foil the Gunpowder Plot. Whether for this reason or others, James showered Andrewes with honors and positions, had him preach often at his court, slept (it was rumored) with Andrewes’s sermons under his pillow, and even restrained his famously foul mouth in the great divine’s presence. The secret to Andrewes’s character, however, was to be found not in his pulpit, nor in his study, nor in James’s court. Rather, it was in his private chapel. Bobrick describes this sanctum as “richly furnished . . . with its silver candlesticks, cushion for the service book, and elaborate Communion plate (‘a silver-gilt canister for the wafers, like a wicker basket lined with cambric lace, the flagon on a cradle, and the chalice covered with a napkin on a credence,’ as scornfully described in a Puritan tract).”

A man of intense piety who spent five hours every morning in prayer, Andrewes kept in that chapel a book of private devotions which, when published after his death, became a classic Anglican guide to prayer. According to some accounts, he died with that book in his hands, stained with the many tears he had cried over the years as he prayed for himself and others. (This perhaps accounts, as Nicolson has speculated, for the “large and absorbent handkerchief” with which Andrewes appears in his portraits.)

The devotion that so characterized him in private also suffused his preaching and writing. For though his preaching was always theological, dealing with every doctrine he felt would edify his congregations, he also understood theology as had the church fathers: it was no abstracted exercise or speculative indulgence for him, but an expression of intimacy between the believer and God.

Andrewes’s experience of God was not just spiritual but visual, physical—and in that sense “Catholic” or “high church.” For he took what Nicholas Lossky calls “an extremely ‘realistic’ approach to the Incarnation.” The fact that God had taken on humanity in the person of Jesus Christ meant for Andrewes that not just our souls but our bodies must take active part in prayer. So he insisted on “worshipping, falling down, kneeling before the Lord” (Psalm 95:6).

“For me, O Lord,” he wrote in one of his prayers, “sinning and not repenting, and so utterly unworthy, it were more becoming to lie prostrate before Thee and with weeping and groaning to ask pardon for my sins, than with polluted mouth to praise Thee.”

This was the man who met, in the famous Jerusalem Chamber in the abbot’s house at Westminster, with the First Westminster Company of Translators. There, in Nicolson’s words, this “scholarly, political, passionate, agonized” man, “in love with the English language, endlessly investigating its possibilities, wordly, saintly, serene, sensuous, courageous,” set upon the King James Bible the stamp of his own character, “as broad as the great Bible itself.”

By Chris R. Armstrong

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #100 in 2011]

Next articles

A few of King James’s approved rules for the new translation

James wanted a popular translation that supported standard Church of England usages

The editorsPre-KJV English translations

The King James Version was not by any means the first English-language Bible

David Lyle JeffreyThe shorter Lord’s Prayer [Luke11:2–4] in early English versions

How the Lord’s Prayer sounded in early English Bibles (Luke’s version)

David Lyle Jeffrey