Others we love, Part 1

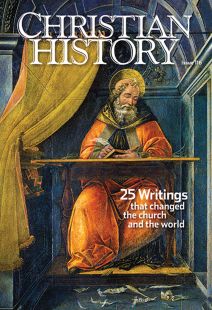

Order Christian History #116: Twenty-Five Writings that Changed the Church and the World in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

THE APOSTOLIC TRADITION

Even Holy Spirit–led religious movements need books of discipline. That’s one of the biggest lessons from reading this early church order, which covers everything from how to ordain a deacon to what jobs are appropriate for a baptized Christian (excerpted in CH 110) to how to conduct your evening devotions. Rediscovered in the nineteenth century, the Apostolic Tradition (c. 200?) was for many years attributed to Bishop Hippolytus of Rome (c. 170–235), a controversial preacher who set himself up as what some call history’s first antipope. When both he and Pope Pontian (ruled 230–235) became victims of Roman persecution and were exiled to Sardinia, they reconciled. Hippolytus was buried as a martyr in Rome with full honors in 236.

Hippolytus wrote something called the Apostolic Tradition, but whether it’s this is under debate. Some argue that it collects material from as late as 400. Its antiquity nevertheless caused church leaders to use it as a model for liturgies adopted by Roman Catholic and mainline Protestant churches in the 1960s and 1970s. My own church still echoes in its prayers many phrases that may first have arisen in third-century Rome from the pen of Hippolytus. —Jennifer Woodruff Tait, managing editor, CH

LIFE OF ANTONY

When Athanasius (pp. 6–8) began his Life of Antony around 362, its subject (250–c. 356) was already famous for demonic battles, distance vision, and faith healing. Monks around the Mediterranean wrote to Athanasius asking “whether the things told of him are true.” Many still ask that question; Athanasius provided no evidence beyond common report.

Antony was 19 when his parents died, leaving him with 300 acres and a sister to care for. Six months later he heard Christ’s words in a church service: “If you would be perfect, go and sell all that you have and give to the poor.” Immediately he sold everything, committed his sister to trustworthy virgins, and left in search of spiritual discipline. He resisted temptations by praying and meditating. Eventually disciples gathered around him. To escape them Antony moved into the Egyptian desert. However he still counseled visitors, instructed groups of monks, and traveled to Alexandria to encourage persecuted Christians. On a visit to Alexandria to denounce the Arian heresy, he met and befriended his eventual biographer, Athanasius.

Antony influenced generations of monks. About 30 years after his death, a sensuous teacher of rhetoric named Augustine read Life of Antony. Impressed by the hermit’s self control (which he lacked), he credited his conversion in part to it. —Dan Graves, layout editor, CH

ON THE UNITY OF CHRIST

In the wake of Protestant liberalism, which split up the so-called Jesus of history and the Christ of faith, a return to early Christian thought about Jesus’ nature is in order. To understand the importance of affirming Jesus Christ as the “Godman,” there is perhaps no better work to read than Cyril of Alexandria’s On the Unity of Christ (440). Cyril’s work exposes the heresy that Jesus was a human being subsequently united to divinity.

Cyril held that the divine person of the Logos, eternally with God the Father, actually becomes a man by being born of Mary. God was not simply united to this man, or somehow in deeper connection with this man: God became this man. And this incredible mystery is precisely what achieves our salvation. “He made it [humanity] his very own,” Cyril wrote, “and thus he restored flesh to what it was in the beginning.” On the Unity of Christ is rooted in Scripture and applies Scripture’s witness to the difficult questions that arise from such an understanding. Its language is clear and its logic easy to follow, making its message, in an age fraught with confusion over who Christ is, profoundly contemporary. —Jackson Lashier, assistant professor of religion, Southwestern College

This article is from Christian History magazine #116 Twenty-Five Writings that Changed the Church and the World. Read it in context here!

By various

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #116 in 2015]

Next articles

Paying back the debt

Anselm’s Why God Became Man [#17] answered an age-old question

Edwin Woodruff TaitIntellect that illuminates Christian truth

Thomas Aquinas’s Summa Theologiae [#2] explained Christianity’s rational basis

Garry J. CritesFollowing Jesus above all

The Imitation of Christ [#10] gave us a model for prayerful living

Paul W. Chilcote