Paradoxes of prison

JERRY MCAULEY (1839–1884) committed every crime short of murder. The Irish-born young man caused so much trouble as a teenager that his grandmother (who was raising him) sent him to relatives in New York City, where he became a street fighter and a “river thief.” Eager to get rid of him, residents of New York City’s Fourth Ward swore he had committed a hold-up, though he always maintained his innocence. He was sentenced to 15 years in Sing Sing Prison.

“Punishment never did me a particle of good, it only made me harder,” he wrote in his memoir. His turnaround began when he attended a prison chapel service and was astonished to discover Orville Gardner, formerly a partner in crime, as the speaker. Gardner wept as he pleaded with prisoners to turn to Christ, prompting McAuley to read the Bible. After weeks of inward struggle, he knelt before God:

It seemed as if a hand was laid upon my head, and these words came to me: “My son, thy sins, which are many, are forgiven.”… God was more merciful to me than man. His pure eyes had seen all my sin, and yet he pitied and loved me, and stretched out his hand to save me. And his wonderful way of doing it was to shut me up in a cell within those heavy stone walls. There’s many a one beside me who will have cause to thank God for ever and ever that he was shut up in a prison.

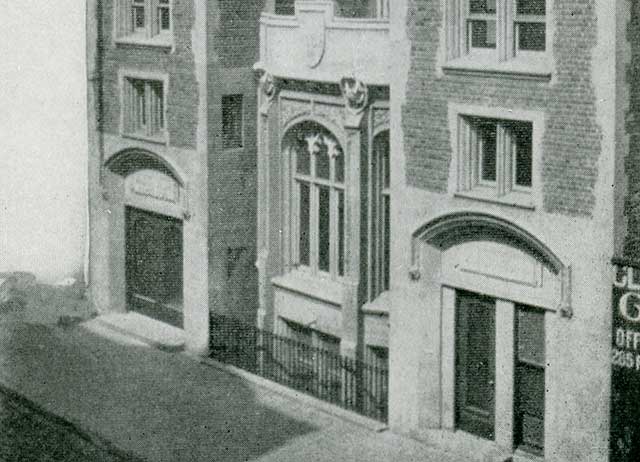

Water Street Mission. Offord, Jerry McAuley an Apostle to the Lost. American Tract Society, 1907

McAuley led several fellow prisoners to Christ: “The love of Christ was so abounding, it drowned every trouble. … If my comrades abused me, I felt that I could pray for and forgive them.” But when released in 1864, the “wavering, unstable, half-and-half faith” of most Christians he met was no help. He relapsed into drink and theft until a Christian worker latched onto him and helped him turn his life around permanently.

What love is this?

Themes in McAuley’s tale recur in the stories of other prison conversions: amazement at God’s grace, profound transformation, struggles to continue in newfound faith, and dealings with those who doubt converted prisoners’ sincerity.

Another common theme has been the desire to evangelize. During the Napoleonic Wars, a French privateer captured an English brig. Among the prisoners of war was African American evangelist John Jea (b. 1773), who in 18 months led 200 fellow prisoners to Christ.

David Berkowitz (b. 1953) was in prison for his role in New York’s Son of Sam murders. Another prisoner provided him with Scripture. Psalm 34:6 shattered his hard shell: “This poor man cried, and the Lord heard him, and saved him out of all his troubles.” Convinced God accepted him for Christ’s sake, he began to do all the good he could for fellow prisoners.

Order Christian History #123: Captive Faith: Prison as Parish in print.

Order Christian History #123: Captive Faith: Prison as Parish in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

He also corresponded with people outside prison, designated his book profits to help victims of crime, and testified about Christ on national TV and through a website detailing his transformation from “Son of Sam” to “Son of Hope.” Out of respect for the families he harmed, Berkowitz has rejected parole. Sounding like McAuley, he wrote, “God actually used our forced confinement in prison to save our lives … he had to use extreme measures to save fools from their own folly.”

Karla Faye Tucker (1959–1998) exercised a similar evangelistic ministry from prison. Her mother had set an example of drug use and schooled her in prostitution at age 14. During a drug-crazed robbery, Tucker helped kill two acquaintances with a pickaxe. Awaiting trial she was intrigued by the peace she saw in a team of ex-cons ministering in jail. To find out more, she stole a Bible (not realizing it was free) and began reading.

Realization dawned on Tucker “that no matter what I had done I was loved,” and it sank in that people were hurting because of her. Tucker became a vibrant death-row evangelist whose prayer ministry and televised testimony reached far beyond her cell. Even relatives of her victims grew close to her and wept on February 3, 1998, when Texas executed her. Among her last words were: “I love all of you very much. I am going to be face to face with Jesus now.”

“Bless you, prison”

In showcasing those who triumph over prison, we risk minimizing the misery of incarceration. Yet prison has proven a blessing for many. In The Gulag Archipelago, his exposé of Soviet prison camps, Alexander Solzhenitsyn (1918–2008) famously wrote,

In the surfeit of power I was a murderer and an oppressor. … it was only when I lay there on rotting prison straw that I sensed within myself the stirrings of good. … And that is why I turn back to the years of my imprisonment and say. … “Bless you, prison!”

After Nicoleta Valeria Bruteanu (1919–1996) was jailed by Romanian Communists for her religious and political convictions, God seemed far away. But one day, “when the cell door closed behind me, I felt another door open within me. … I wanted to make peace with myself and God.” She held firm under torture and scratched psalms memorized in childhood onto her cell wall. “I never was closer to God than I was in prison,” she asserted.

Playwright Silvio Pellico (1789–1854) was imprisoned for revolutionary associations. The experience prompted his gripping, widely read autobiography, My Ten Years Imprisonment (1832): “To awake the first night in a prison is a horrible thing,” he wrote. “Strange this should be the first time I truly felt the power of religion in my heart.” He described in detail the reasoning that soon led him to declare himself “openly a Christian.”

Armando Valladares (b. 1937) was 23 when he went to prison in Cuba for refusing to allow a Communist slogan on his desk. He spent 22 years in cruel conditions that he later described in Against All Hope (2001), a powerful exposé of Castro’s brutal regime:

Every night there were firing squads. There came a moment when, seeing those young men full of courage depart to die before the firing squad and shout “Viva Cristo Rey” at the fateful instant, I … understood instantly, as though by a sudden revelation, that Christ was indeed there for me. … Those cries of the executed patriots—“Long live Christ the King! Down with Communism!” had wakened me to a new life.

Convert or counterfeit?

Such stirring testimonies raise the question: how real are most prisoner conversions, especially when conversion takes place in a setting where it might ingratiate authorities? A nineteenth-century English report dryly remarked that requiring religious devotional exercises of prisoners caused them to add hypocrisy to all their other crimes. Sociologist Byron Johnson found that recidivism rates for Florida’s prison converts were no better than for nonconverts. Such outcomes can lead to cynicism.

Acquaintances of “Happy Jack” Burbridge (1937–2015) thought his conversion was faked to gain early release. Drug dealer, pimp, and enforcer, he lost his family following a crime spree. On his way to jail, the words of a Christian policeman brought Burbridge under conviction: “God had to show me His standards in the form of Mr. Lytton before I could see how bad off I was,” he wrote in The Enforcer (1980).

After his conversion he admitted his guilt in court as evidence of a newfound commitment to truth, convinced that Christ expected no less. After his release, past confederates expected him to revert to crime. When that didn’t happen, they surmised he was waiting for his parole to expire. Instead Burbridge got his family back and returned to prison repeatedly as a soul-winning evangelist for From Crime to Christ Ministries.

Watergate conspirator Charles Colson (1931–2012) silenced some of his detractors and proved the sincerity of his conversion by founding Prison Fellowship after serving time. “I shudder to think of what I’d been if I had not gone to prison,” he said. Jeb Stuart Magruder (1934–2014), also imprisoned for his role in Watergate, attended divinity school after his release and served for years as a Presbyterian minister.

And in the end, Jerry McAuley’s conversion proved real too. He founded the first city rescue mission in the United States, Water Street Mission, and led a revival in New York that reached into the highest levels of society. When Christ comes alongside a prisoner, he makes possible the paradoxes of prison—the unlovable discovering love, the irredeemable finding redemption, captives becoming transcendentally free. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #123 Captive Faith. Read it in context here!

By Dan Graves

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #123 in 2017]

Dan Graves is the layout editor for Christian History, writes Christian History Institute’s “This Day in Christian History” feature, and maintains the website Captive Faith.Next articles

Christian History Timeline: Crime and punishment

Prisons, prison ministries, and Christians

the editorsPrison as a parish: Christian responses

How Christians have tried to reform the justice system and minister to prisoners

Todd V. CioffiWilliam Morgan’s gift

An obscure Irish teenager inspired Methodists to Undertake over 200 years of prison ministry

Kevin M. Watson