William Morgan’s gift

IN 1732 A YOUNG MAN named William Morgan died in Dublin.

The young Irishman had come to Oxford University as a student in 1729. There, amid the usual collegiate crowd more interested in social life than studies, Morgan was two unusual things: a serious student and a serious Christian. He quickly became friends in May 1729 with another young man in the same boat: Charles Wesley (1707–1788).

Charles’s older brother, John (1703–1791), was serving in local church ministry in Epworth and Wroot.When he returned to Oxford in the summer of 1729, he promptly joined with Charles and William to encourage one another in their faith.

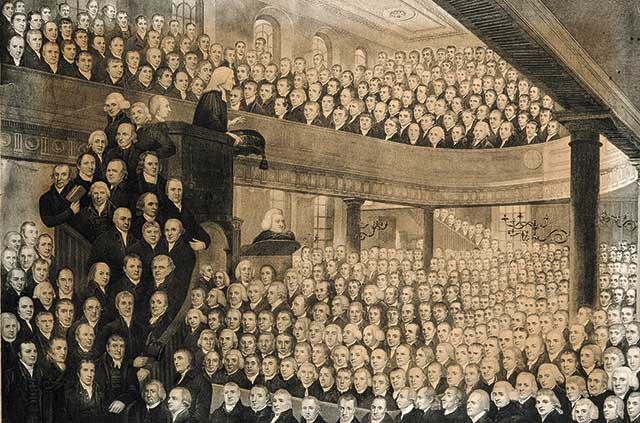

[John Wesley preaching. Wikimedia / Wellcome pictures.]

They attended Communion, studied, prayed, and fasted together. Other undergraduates called them names: the Reforming Club, the Godly Club, the Holy Club, Sacramentarians, Bible Moths, Bible Bigots, Supererogation Men, Enthusiasts—and, because of their methodical approach to the spiritual life, the name that eventually stuck: Methodists.

“That ridiculous society”

These young scholars weren’t content to merely study together. At Morgan’s urging they soon turned their youthful zeal toward action—visiting the poor, the sick, and prisoners. Richard Morgan, William’s father, was displeased with his son’s actions, writing to him from Ireland in 1732:

You can’t conceive what a noise that ridiculous Society which you are engaged in has made here. Besides the particulars of the great follies of it at Oxford, which to my great concern I have often heard repeated, it gave me sensible trouble to hear that you were noted for your going into the villages about Holt, entering into poor people’s houses, calling their children together, teaching them their prayers and catechism, and giving them a shilling at your departure.

I could not but advise with a wise, pious, and learned clergyman. He told me that he has known the worst of consequences follow from such blind zeal, and plainly satisfied me that it was a thorough mistake of true piety and religion.

Soon William Morgan died—on August 26, 1732—and his father thought the Wesleys’ rigorous religious routine, which involved fasting as well as visiting the poor and prisoners, played a role in his death. Richard Morgan wrote to Charles, “The Wesleys he raved of most of all in his sickness.”

John Wesley responded. As with most things John wrote, he later published his letter to Richard. It became the first public defense of Methodism, including the prison ministry instituted by William Morgan:

In November 1729, at which time I came to reside at Oxford, your son, my brother, myself, and one more, agreed to spend three or four evenings in a week together. Our design was to read over the classics, which we had before read in private, on common nights, and on Sunday some book in divinity.

In the summer following Mr. M[organ, i.e. William] told me he had called at the jail to see a man who was condemned for killing his wife, and that, from the talk he had with one of the debtors, he verily believed it would do much good if anyone would be at the pains of now and then speaking with them. This he so frequently repeated that on the 24th of August, 1730, my brother and I walked with him to the Castle.

We were so well satisfied with our conversation there that we agreed to go thither once or twice a week; which we had not done long before he desired me to go with him to see a poor woman in the town who was sick.

In this employment too, when we came to reflect upon it, we believed it would be worth while to spend an hour or two in a week, provided the minister of the parish in which any such person was were not against it.

Order Christian History #123: Captive Faith: Prison as Parish in print.

Order Christian History #123: Captive Faith: Prison as Parish in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

Preaching in prison

Before long, John explained to Richard Morgan, visiting prisoners in Oxford became a part of the weekly discipline of John, Charles, William Morgan, and Bob Kirkham, who was the fourth to join with them. John told Morgan’s father that the Oxford Methodists had asked for permission from the bishop of Oxford’s chaplain to meet with the prisoners who were “condemned to die.”

John had also expressed his intention to preach in prison once a month if the bishop approved. They not only received approval for all of this but, John explained to Morgan’s father, the bishop had said he “was greatly pleased with the undertaking, and hoped it would have the desired success.”

John delivered on those commitments, preaching in the Castle prison at least once a month for the next four and a half years and visiting prisoners multiple times each week. He wrote down his weekly schedule in the front of his 1731 diary, which recorded that he would visit the Bocardo prison on Monday and Friday and the Castle prison on Tuesday and Saturday.

Meeting with prisoners became a central Methodist ministry and a bridge to other acts of mercy, especially to the poor and sick. Morgan had brought together children from the poorest families in Oxford, and at the end of June 1731, John Wesley hired a woman named Mrs. Plat to care for them. In his 1731 diary, John listed Wednesday as a day he would visit with these children; Sunday he set aside to visit with the “poor and elderly.”

In 1735, three years after Morgan’s death, John and Charles Wesley and others traveled to the colony of Georgia as missionaries, disrupting the stability of the Holy Club. However the influence of William Morgan and his commitment to the downcast would live on.

When John returned from Georgia in 1738, he continued to preach in the Oxford prisons; Charles also continued prison ministry with those condemned to die. (Given the numerous offenses the English penal code of the time punished with death, there were many of these.)

One passage in Charles’s journal in 1738 describes how he visited with a group of prisoners during their last hours, offering Holy Communion, singing hymns with them, and accompanying them to the place of execution. In one chilling note, he wrote, “By half-hour past ten we came to Tyburn … waited till eleven; then were brought the children appointed to die.”

In 1742 Charles published a “Hymn for Condemned Prisoners.” Soon John set out three requirements for any person who wanted to continue as a Methodist in his short tract The Nature, Design, and General Rules of the United Societies (1743): “doing no harm,” “doing good,” and “attending upon all the ordinances of God.” Among the ways Methodists went about “doing good” was “by giving food to the hungry, by clothing the naked, by visiting or helping them that are sick, or in prison.” Prison ministry, originally Morgan’s idea, had become woven into the very fabric of the Methodist understanding of Christian discipleship.

“Almost naked”

John Wesley continued to preach and minister in prisons throughout his life. In 1748, after preaching in Dublin prisons, he wrote in his journal that “the poor prisoners, both in the Castle and in the city prison, had now none that cared for their souls; none to instruct, advise, comfort, and build them up in the knowledge and love of the Lord Jesus.”

In October 1759 (more than 25 years after Morgan’s death), John visited French prisoners at Knowles and found that “a great part of these men are almost naked.” He immediately wrote a letter to the editor of Lloyd’s Evening Post seeking to raise the public’s awareness of their condition and exhort people to provide appropriate clothing for the winter months. Just over two weeks later, he wrote the editor of the Morning Chronicle describing the collection he had taken for these same prisoners:

On Tuesday, October 16 last, I made a collection at the New Room in Bristol for the French prisoners confined at Knowles. The money contributed then and the next day was about three-and-twenty pounds.

Judged it best to lay this out in shirts and flannel waistcoats, and accordingly bought, of Mr. Zepheniah Fry, in the Castle, check shirts and woollen cloth to the amount of eight pounds ten shillings and sixpence; and of Mrs. Sarah Cole, check linen to the amount of five pounds seventeen shillings.

The money remaining I lodged in the hands of Mr. James Ireland of Horsleydown Street, as he speaks French readily, and Mr. John Salter of Bedminster, who had been with me both at the prison and the hospital. I directed them to give a waistcoat and two shirts to every one who was remanded from the hospital to the prison, and the other half to those they should judge most needy or most deserving.

Similar stories weave throughout John Wesley’s journal. Richard Morgan had thought his son and the Wesleys were making a “thorough mistake of true piety and religion.” But as long as Methodists followed the General Rules, they understood “doing good” to include ministry with those in prison.

In 1784, at age 81, John Wesley said of one prison preaching experience in London:

I preached the condemned criminals’ sermon in Newgate. Forty-seven were under sentence of death. While they were coming in, there was something very awful in the clink of their chains.

But no sound was heard, either from them or the crowded audience, after the text was named: “There is joy in heaven over one sinner that repenteth, more than over ninety and nine just persons, that need not repentance.” The power of the Lord was eminently present, and most of the prisoners were in tears. A few days after, twenty of them died at once, five of whom died in peace.

In 1785, at the age of 78, Charles Wesley published an entire hymnal for prisoners, Prayers for Condemned Malefactors, that drew on his continued prison ministry. One of its final hymns offers grace to sinners, whether in prison or not, with these words:

And let these wretched bodies die,

If thou at last receive

The souls thou didst so dearly buy,

That we with God might live:

Death as the wages of our sin,

Our just desert we claim,

But hope eternal life to win,

Through grace—and Jesu’s name.

Jesus, thou all-redeeming Lord,

Remember Calvary,

And think on sinners self-abhorred,

Who gasp in death to thee:

And while thy mercy’s utmost power

On us is magnified,

O save us at our latest hour

Who hast for felons died! CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #123 Captive Faith. Read it in context here!

By Kevin M. Watson

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #123 in 2017]

Kevin M. Watson is assistant professor of Wesleyan and Methodist studies at Candler School of Theology at Emory University, and the author of several books on Wesleyan discipleship and the Wesleyan class meeting.Next articles

“Heaven at last the wrong shall right”

One man’s thwarted attempts to change American prisons

Jennifer GraberJoys and challenges

What does prison ministry look like today? We Interviewed five individuals active in prison ministry to get first-hand accounts.

Jim Forbes, Christiana DeGroot, Joe Roche, Jack Heller, Susannah Moore