Picturing saints

[Detail from Bernini’s Ecstacy of Teresa; Wikipedia]

IN THE WAKE of the Protestant Reformation, what piety looked, smelled, sounded, and tasted like varied depending on where you were.

In Germany Luther’s reform had challenged the hierarchical structure of the Roman Church, with its privileged priesthood, sacraments, and the language of Latin for church services. Consequently while Lutherans kept a role for music and religious art, they rejected the saints as intercessors, the priesthood as a special class, and Latin as the language of worship. At the same time, more radical resistance to Rome grew in France and Switzerland. The Reformed expressly condemned imagery in all forms. Their iconoclastic campaigns stripped churches of statues, wall paintings, and stained glass.

The Catholic Church responded to Protestant critiques of its piety, in essence, by doubling down on the role of art and music as well as by convening the Council of Trent (1545–1563; see “The persistent council,” pp. 19–22). Pope Pius IV promulgated the Tridentine Profession of Faith, a product of the Council, on November 13, 1564. Explicit references to images and to the intercessions of the saints were included in the declarations it asked Catholics to subscribe to:

I steadfastly hold … that the saints reigning together with Christ should be venerated and invoked, that they offer prayers to God for us, and that their relics should be venerated. I firmly declare that the images of Christ and of the Ever-Virgin Mother of God and of the other saints as well are to be kept and preserved, and that due honor and veneration are to be given them….

Step inside the story

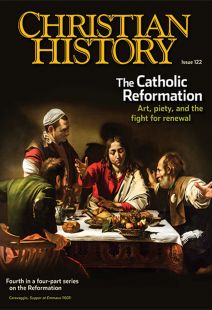

Where did these images come from? Artists created them, as they had for centuries. As the Catholic Reformation unfolded, many Catholic artists adopted dramatic presentations to persuade the viewer of Catholic truths, with large, allegorical themes and complex, dynamic compositions. This realism was heightened by strong contrasts of light and shadow, a technique whose greatest master was the influential Italian Baroque painter Caravaggio (1571–1610; see the cover and p. 24). Artists presented emotionally resonant characters, endeavoring to help the spectator empathize with the story.

For example Mary Magdalene is one of the most beloved of Christian saints. Her character, as represented by artists, drew on different sources: the female sinner who washed Christ’s feet with her tears (Luke 7:36–50), the woman who stood beneath Christ’s cross (Matthew 27:56), and the Mary who came to anoint Christ’s body at his tomb to find that he had risen (John 20:14–16).

We see the dramatic way Catholic artists portrayed her in the sixteenth century in The Repentant Magdalen, about 1577, by El Greco (p. 17). Born Doménikos Theotokópoulos (1541–1614) in Greece, he migrated to Madrid, ultimately settling in Toledo, at that time the religious capital of Spain. (El Greco is Spanish for “The Greek,” as he became known.) In the painting at right, we see her unguent jar (for anointing Christ) and a skull, a symbol of meditation on judgment and death.

Spain continued to be a center of Catholic art as it continued to staunchly support the Catholic faith throughout the sixteenth century and into the seventeenth (see “Reasons of state,” pp. 28–32). A key Spanish artist, Francisco Pacheco (c. 1564 –1644), highly intelligent and deeply devout, wrote a number of works on painting, including appropriate ways to represent the stories of the Bible and of the saints. He advocated the importance of modest clothing and of showing the nobility of holy figures, even when subject to torture or death. The figures, he argued, should be anatomically correct, different from the elongated proportions of El Greco.

Pacheco was influential for two reasons. The first was his pupils, especially famed painter Diego Velázquez (1599–1660), who married Pacheco’s daughter. The second was because he held the post of censor for the Inquisition in Seville. (The Spanish Inquisition had been established in 1478 to combat heresy in Spain; in 1538 and 1542 similar groups came into being in Portugal and Rome.)

Christ Carrying the Cross, by Alonso Cano (1601–1667; see p. 18), exemplifies Pacheco’s directives. Christ is dignified and clothed in a long tunic, although we also see realistic details such as the rope around his neck, the crown of thorns on his head, and his blood-stained brow.

Seeing visions

The Catholic Reformation also wished to depict its major thinkers. Ignatius of Loyola (1491–1556) was certainly one of its brightest lights (see “Helping souls,” pp. 6–11). After an early career as a soldier, a serious wound led Ignatius to the decision to enter the church. His Society of Jesus became one of the most successful proponents of a reinvigorated Catholic spirituality, one that stressed individual discernment linked to rigorous training in argument and rhetoric.

Order Christian History #122: The Catholic Reformation in print.

Subscribe now to get future print issues in your mailbox (donation requested but not required).

The Jesuits became missionaries in the Far East and the New World, developing the church’s most prestigious educational systems. Giovanni Battista Gaulli (1639–1709), known as Baciccio, was chosen to paint the ceiling decoration of the mother church of the Jesuits (known as the Church of the Gesù) in Rome between 1681 and 1685. Gaulli’s ceiling frescoes create the illusion that the viewer is witnessing God blessing the triumph of the work of the society. Sculptures at the edges blend with painted figures, which heightens the illusion of an actual glimpse into heaven.

Baciccio’s The Vision of Saint Ignatius (1684–1685, above) is a preparatory study for a wall painting at the Gesù, apparently not executed. It demonstrates typical Counter-Reformation art: energetic compositions invariably structured along dramatic diagonals. The image shows Ignatius in 1537, north of Rome in a place known as La Storta. There he recorded that he received a vision of God the Father and Christ, who instructed him to establish the society.

Alongside the flowering of art and music, a passionate and dramatic mysticism flourished in the Catholic Reformation, exemplified especially by Teresa of Ávila (1515–1582). This Spanish mystic and reformer joined the Carmelite Order in 1535. One year later she experienced significant illness, including partial paralysis. During her healing process, she meditated on Christ’s Passion and, as she wrote later, saw visions of him to which she attributed her healing.

A long spear of gold

Teresa’s campaigns to reform her order faced opposition but were ultimately successful; she founded the convent of Discalced Carmelite Nuns of the Primitive Rule of Saint Joseph at Ávila in 1562. Along the way, she became friends with Carmelite priest Juan de Yepes y Álvarez (1542–1591), who founded a monastery for men along the lines of Teresa’s reforms and changed his name to Juan de la Cruz (John of the Cross) in 1568.

Teresa’s influence extended to religious and secular leaders of her time through numerous writings, including The Way of Perfection (1583), The Interior Castle (1588), and her widely read autobiography, The Life of Saint Teresa of Ávila by Herself (1565). One of her best-known poems states: “Let nothing disturb you. Let nothing make you afraid. All things are passing. God alone never changes.” Her disciple John’s poem “The Dark Night of the Soul” and mystic treatises Ascent of Mount Carmel and The Spiritual Canticle (all first published in 1618) had a profound influence on later Christian spiritual reflections.

Artists picked up on these mystical themes. Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680; see p. 16) depicted a well-known vision of an angel described in Teresa’s autobiography some decades after her death in a renowned Baroque sculpture in the church of Santa Maria de Vitoria in Rome. The sculpture Ecstasy of St. Teresa (1647–52) echoes her text: “I saw in his hand a long spear of gold, and at the point there seemed to be a little fire. He appeared to me to be thrusting it at times into my heart, and to pierce my very entrails; when he drew it out, he seemed to draw them out also, and to leave me all on fire with a great love

of God.”

On either side Bernini gives the impression that spectators are looking on from illusionary balconies. The original spectators are long gone: it is left to us to observe, as they did, Teresa on fire for the love of God. CH

This article is from Christian History magazine #122 The Catholic Reformation. Read it in context here!

Christian History’s 2015–2017 four-part Reformation series is available as a four-pack. This set includes issue #115 Luther Leads the Way; issue #118 The People’s Reformation; issue #120 Calvin, Councils, and Confessions; and issue#122 The Catholic Reformation. Get your set today. These also make good gifts.

By Virginia C. Raguin

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #122 in 2017]

Virginia C. Raguin is Distinguished Professor of Humanities at the College of the Holy Cross and author of Stained Glass: Radiant Art and Art, Piety, and Destruction in the Christian West, 1500–1700.Next articles

Christian History Timeline: The Catholic Reformation

The Christian History Timeline compiled from issues 5, 12, 34, 39, 48, 115, and 118, with additions by the editors

the editors