Power in the blood

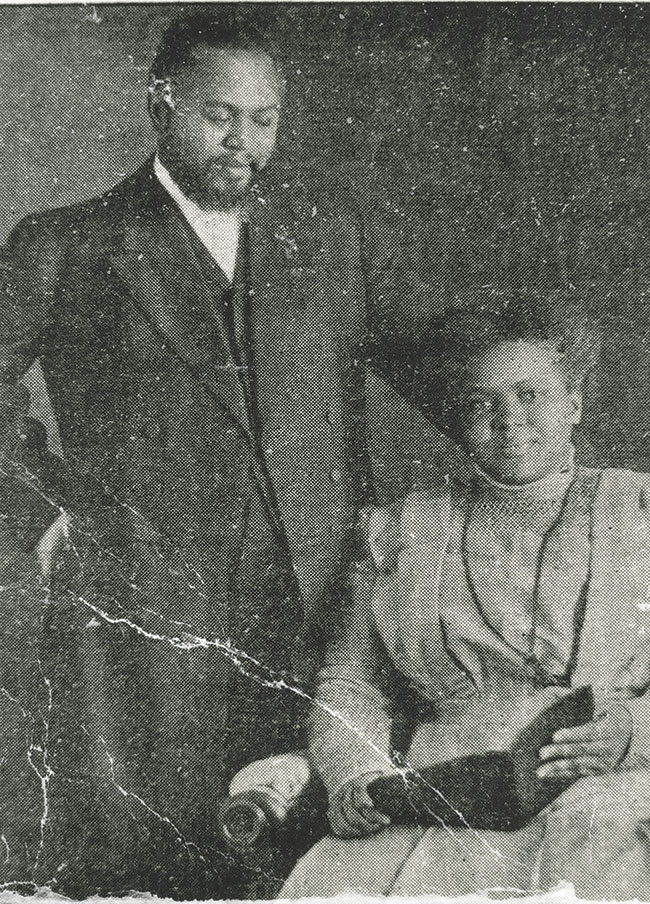

[Above: William J. Seymour with wife, Jennie Moore Seymour, 1912. Unknown Photographer—Used by permission of Flower Pentecostal Heritage Center]

“Aleluya, Aleluya!,” a Mexican immigrant exclaimed at the Azusa Street Revival in 1906 as he rapidly walked up and down the aisle, reporting with joy the healing of his club foot. He was one of thousands of visitors who flocked to the Azusa Street Mission from 1906 to 1931 in search of healing for their broken bodies, minds, and spirits.

The revival’s leaders believed that if Christians could come together in racial unity across unbiblical social divisions (race, class, gender, nationality) the Holy Spirit would give them the power through Jesus’s victorious atoning death on the cross to carry out signs and wonders via divine healings, miracles, and other supernatural manifestations that would in turn enable them to help bridge the racial divide and help usher in the Second Coming of Jesus Christ.

Sin, death, unity, healing

William J. Seymour (1870–1922) not only led the revival, but created this powerful message and vision of healing. He was an African American holiness preacher, originally from Louisiana, who had lived and preached across the Midwest and in Texas (see CH 58). He arrived in Los Angeles to pastor a holiness church, but when the pastor discovered he believed in speaking in tongues, she padlocked the doors against him.

Seymour and some friends began a prayer meeting in a local home that quickly turned into a full-blown revival after they moved to 312 Azusa Street, in the heart of the Black community. They met in the former Stevens African Methodist Episcopal Church that had since been turned into a barn and storage facility. The first supernatural manifestation of the Holy Spirit reportedly took place the day before the revival officially began. Three Black women were preparing the new mission for its grand opening and paused to pray for a Mexican day laborer. He was so moved by the Spirit that he dropped to his knees and broke down in tears.

Seymour and his followers created a theology of divine healing that seamlessly wove together the overcoming power of Jesus’s atoning death and Resurrection with the Great Commission. They believed that Jesus’s victory over the power of sin, sickness, and death through his death and Resurrection are connected to the commission to evangelize all nations by the power of the Holy Spirit—a commission that fell on Jesus’s disciples gathered in unity from all over the world on the day of Pentecost.

For early Pentecostals the linchpin for divine healing was the atonement. The blood of Jesus on the cross breaks the power and fear of original sin, disease, and death over a believer asking in faith and with a sincere heart, because “[by] his stripes we are healed” (Isa 53). They loved to sing about the power of Jesus’s atoning blood on the cross in the famous old hymn “Power in the Blood.” They also taught that all of the spiritual gifts practiced in the New Testament church are available to all born-again, Spirit-filled believers—including “sign gifts” of divine healing, miracles, prophesy, and speaking in tongues (1 Cor 12; Mark 16:15–20). Early Pentecostals believed these gifts did not cease with the death of the apostles, but are available today to all who ask in faith.

Pentecostals based this belief on John 14:12 and on the Great Commission in Mark 16:15–20, where Jesus called on his followers to preach the gospel around the world with signs and wonders such as placing their hands on and healing the sick. They connected the outpouring of the Holy Spirit through gifts and healing with the fulfillment of the Great Commission to all nations and racial-ethnic groups using Joel 2:28–30, Acts 1:8, Acts 2:4, 4:12, and Hebrews 13:8.

This focus on racial unity as a necessary precondition for the practice of divine healing fostered a ministry of racial reconciliation, a huge contributor to the movement’s rapid growth across the United States (especially among racial-ethnic minorities) and around the world (especially in the Global South). Indeed Seymour’s distinctive message was transported globally via thousands of visitors (including many pastors, evangelists, and seasoned missionaries) and the 405,000 copies of his Apostolic Faith newspaper circulating around the world.

Pentecostals justified their message of racial unity as a precursor to healing by invoking biblical precedent. They saw the intersection between healing, evangelism, and racial reconciliation in the stories of the Samaritan woman (John 4:4–26), the Roman centurion (Matt 8:5–13 and Luke 7:1–10), the Syrophoenician woman (Mark 7:24–30), the Ethiopian eunuch (Acts 8:26–40), and in Paul’s ministry to the Gentiles, especially his rebuke of Peter’s Jewish ethnocentrism (Gal 2:11–20). They interpreted the day of Pentecost in Acts 2:4 as a prime example of how Jesus’s followers from around the world had transcended divisions. They also saw how Jesus and his disciples interacted with and often laid hands on the sick and suffering across racial and social boundaries.

Laying on of hands

Seymour taught that the Holy Spirit freely gives spiritual gifts to all born-again believers who earnestly and sincerely desire them. Thus an economically impoverished Black woman might be called on at a revival meeting to use her gift of divine healing to lay hands on a White man to be healed of his affliction. Or, a working class Black or Mexican immigrant might be called on to lay hands on and pray for the healing of a White woman of wealth. This cross-racial interaction and physical contact scandalized Americans and many around the colonized world, and is also why Azusa Street and its daughter missions became such a curious and powerful magnet. This—perhaps as much as any other thing—was Azusa Street’s healing miracle.

The threefold purpose of divine healing was to bring relief to the person suffering, to attract the lost and backslidden, and to demonstrate to the unbelieving world God’s miraculous power to heal and overcome sickness, the devil, and this fallen world. Sin and sickness were not limited to physical ailments, but also included emotional, spiritual, and psycho-societal ones—including racial prejudice.

Seymour preached that race prejudice divides up Christ’s church and separates people with human distinctions when no such distinctions exist in heaven. The health, salvation, and unity that divine healing brings to body, mind, spirit, and community has the power to transcend and transform this societal sin.

Seymour linked all of these things when he wrote in “The Way into the Holiest” that Jesus sanctified “spirit, soul, and body. . . . So we get healing, health, salvation, joy, life—everything in Jesus!” Seymour’s newspaper Apostolic Faith boldly declared at the height of Jim Crow America, “God makes no difference in nationality, Ethiopians [Blacks], Chinese, Indians, Mexicans, and other nationalities worship together” because “God recognizes no man-made creeds, doctrines, or classes of people, but ‘the willing and the obedient’.”

The newspaper affirmed that “no instrument [of God] is rejected on account of color. . . . One token of the Lord’s coming is that He is melting all races and nations together. . . . He is baptizing by one spirit into one body and making up a people that will be ready to meet Him when he comes.”

The revival encouraged biblically based interracial worship, friendships, relationships, and the laying on of hands to pray for divine healing. This profound belief in the power of prayer and the power of the atonement prompted people to gather together in integrated services to sing, worship, and testify. Eyewitness Frank Bartleman famously quipped that the “colorline was washed away in the blood” of Jesus. Seymour also crossed lines of gender, class, and nationality. He allowed men and women, poor and rich, and citizens and immigrants alike to worship freely together and lay hands on and pray for one another.

Seymour’s conviction that God disregards human distinctions and simply recognizes the willing and the obedient was shared by others such as attendee Mattie Cummings, who stated, “It didn’t matter if you were black, white, green or grizzly. There was a wonderful spirit. Germans and Jews, blacks and whites, ate together. . . . Nobody ever thought about color.”

The socially transgressive nature of the actions at Azusa Street was spotlighted and mercilessly mocked by established churches and the mainstream press and society, which often denigrated them as “darky camp meeting antics” where divine healing and miracles played a critical role.

On April 18, 1906, the Los Angeles Times described the revival as a “Weird Babel of Tongues” where Black women and men and a sprinkling of Whites had gathered together to speak in unknown tongues and pray for the sick, including a Rabbi Gold who claimed he was healed that night. The Indianapolis Star wrote that Seymour scandalously led a service during which one “white fellow kissed a negro.” Another newspaper later lamented that Seymour’s daughter missions in Africa had promoted “brand new American ideas” about “social equality between White people and the [Black] natives.”

Asking in faith

Pentecostals recognized divine healing and miracles as distinct but interrelated gifts of the Holy Spirit and almost always talked about them together, sometimes even interchangeably. They believed being healed was open to anyone who asked in faith and should be a normal part of the Christian life. In fact Seymour believed that one of the three key duties of a pastor, after preaching and meeting with members of the church for spiritual formation, is to visit the sick and, when the opportunity arises, to pray for healing.

He and his followers at first believed that Christians should avoid medicine and simply pray, although they modified this view very early in the movement, encouraging people to first anoint and pray for the sick person, and then take medicine if and as needed.

Divine healing could be a one-time act of faith whereby a person prays for someone to be healed or it could be a spiritual gift that the Holy Spirit imparts to someone to build up the body of Christ and pray for sick believers or nonbelievers. While anyone can be healed, Seymour and early Pentecostals emphasized that the spiritual gift of divine healing could only be effectual if the praying person is a born-again, Spirit-filled Christian living a holy and pure life—free from habitual unrepentant sin.

Most believed that the effectiveness of a person’s prayers is directly tied to the praying person’s personal faith, holiness, and theological and moral purity. They often cited James 5:16 in the King James Version: “The effective, fervent prayer of a righteous man availeth much.”

Backsliders returning

Revivalists also taught that divine healing, miracles, and spiritual gifts are a sign of the latter-day prophesied outpouring of the Holy Spirit helping to usher in Jesus’s Second Coming. Seymour wrote that: “When we get the power of the Holy Ghost, we will see . . . power over sickness, diseases and death . . . the Lord never revoked the commission he gave to his disciples: ‘Heal the sick, cleanse the lepers, raise the dead.’” Jesus would perform this “if we can get a people in unity.”

The movement brought people together around the world. Andrew Johnson wrote in Sweden that “many sick have been healed, sinners saved, and backsliders coming to the Lord,” and in India others wrote how some missionaries were “much used in laying on of hands for the healing of the sick.” In southern Africa, Black and Dutch Afrikaner evangelists reported healing and even raising Zulus from the dead at their revival services, which led to jam-packed meetings and scores of conversions.

Apostolic Faith described Azusa Street as the beginning of a worldwide revival. Indeed, people of 20 nationalities reportedly attended, and by 1914 it had spread across diverse cultures and societies on six continents. Today, divine healing remains one of the most important factors in the continuing growth of the movement as people worldwide continue to echo the cry of “power in the blood.” CH

What got healed?

The Apostolic Faith newspaper reported many different types of healing and miracles either at the mission itself or its daughter missions around the world. Conditions reported as healed included abscesses; addictions to alcohol, tobacco, or drugs, including opium and morphine; asthma; cancer; chills; deafness; demonic manifestations; eczema; epilepsy; eye problems, including blindness and cataracts; fever; hemorrhage; hernia; injury or malfunction of an ankle, foot, head, heart, leg, muscle, shoulder, spine, or wrist; mental illness; paralysis; pneumonia; poisoning; rheumatism; skin diseases; tuberculosis—and many others!

By Gastón Espinosa

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #142 in 2022]

Gastón Espinosa is the Arthur V. Stoughton Professor of Religious Studies at Claremont McKenna College and the author of nine books, including Latino Pentecostals in America: Faith and Politics in Action and William J. Seymour and the Origins of Global Pentecostalism.Next articles

Extraordinary becoming ordinary

Charismatic renewal and healing prayer in mainline denominations

Amy Collier ArtmanHealing power

How a pastor and a professor prayed for healing and started the third wave movement

Caleb Maskell