Prayer, provision, service

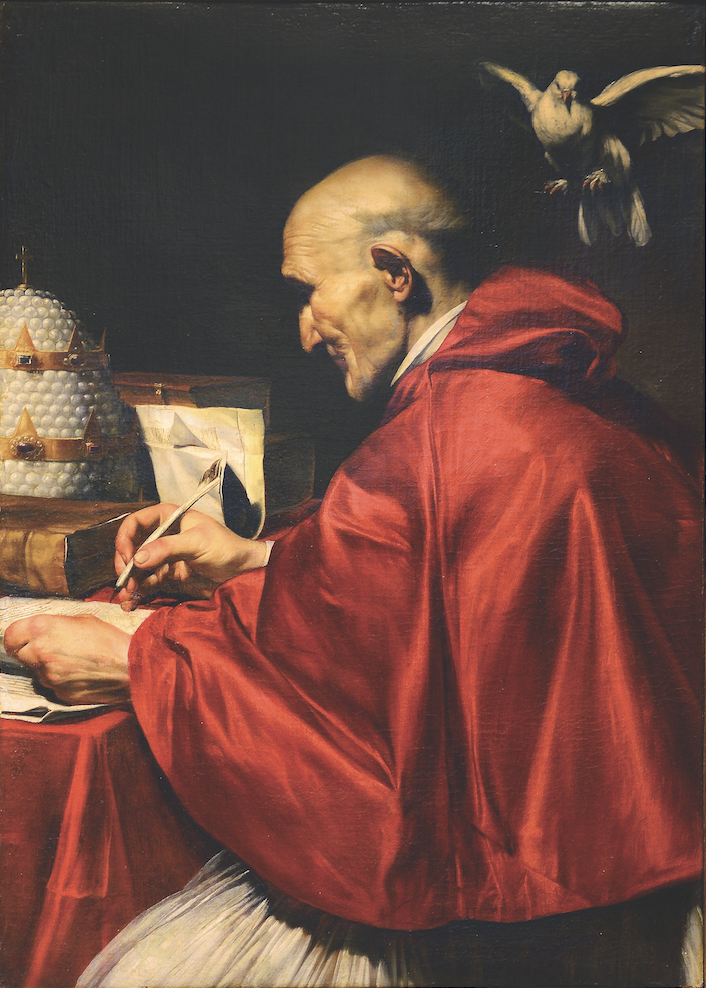

[Above: St Gregory the Great by José de Ribera—Livioandronico2013 / [CC-BY-4.0] Wikimedia]

Let brethren returning from a journey . . . seek prayers from all on account of transgressions. . . . And by no means let any one of them presume to relate to another anything whatsoever that he may have seen or heard outside the monastery, because it is very distracting.—The Rule of St. Benedict, chapter 67

At first blush this monastic call for disengagement with the secular world seems to allow monastics little interest in public life and service to the wider community. Yet monasteries were huge engines of economic production, improving lands, breeding better livestock and crop plants, and reproducing scarce books. They traded with surrounding communities, and monks were increasingly recruited for civic functions—they were literate and assumed to be more impartial in matters of justice and politics than the local gentry. Monastic withdrawal often formed leaders who emerged on a local, national, or even international stage.

Generous hospitality

Two of these leaders, and two monastic voices among many in the West that illustrate this contradiction, are Benedict of Nursia (c. 480–547) and Pope Gregory I “the Great” (c. 540–604), who popularized Benedict’s life story.

Benedict was the son of a noble Roman family in Nursia in northern Italy; he set out around the age of 20 to study in Rome but quickly became dissatisfied and left. After time as a hermit and then as the unsuccessful abbot of an already-existing monastery near Subiaco, he began founding his own monasteries—13 in all, the last one the famous Monte Cassino near Rome. It was for Monte Cassino that Benedict wrote the Rule that still governs the Benedictine order.

In Benedict’s vision—expressed in the prologue to his Rule—the community is a “school of the Lord’s service,” an “institution of which we hope we are going to establish nothing harsh, nothing burdensome.” Despite emphasizing the renunciation of worldly pursuits and devotion to spiritual work, Benedict promoted hospitality to outsiders. The Rule makes provision for outsiders’ arrival: “Let all guests that happen to come be received as Christ.” Service to guests and the poor was a key part of the monastic life (see p. 15 for more details from the Rule).

One reason we know as much as we do about Benedict is that his faithful life caught the attention of Gregory. Gregory is known for a number of important commentaries, sermons, and letters, but also for the Dialogues, four books on holy men of the sixth century and the various miracles, signs, and healings they had performed. In the Second Book of Dialogues, Gregory praises Benedict as a hero and portrays him predominately as a miracle worker.

These miracle stories focus not only on Benedict’s personal piety, or even on his skills as a practical organizer and spiritual father of his community as seen in the Rule. Rather, Gregory told of miracles of Benedict that helped and healed those in his monastic and wider community. Gregory focused also on Benedict’s relief of poverty and hardship, with tales of how he brought water from a rock, revived the sick, paid the debts of the poor, and filled an empty barrel with oil. While most monks could not expect to perform such miracles, all could expect to be guided by Benedict’s example in their daily civic engagement.

Refocusing on the poor

Gregory’s own life demonstrated the same tension and rhythm between monastic life and the wider community. Gregory’s family background was similar to Benedict’s. He was born Gregorius Anicius to a wealthy Roman noble family in a villa on the Caelian Hill, one of the famous seven hills of Rome, and raised in a period of distress—during the Plague of Justinian in the mid-540s, a pandemic that killed about a fifth of the city’s population. Famine and political unrest were also common.

Gregory’s father, Gordianus, a prominent political and church administrator, influenced his son’s future trajectory. (Gordianus may have been the great-grandson of Pope Felix III, and Gregory’s mother, Silvia, was well-born.) Gregory became an urban prefect of Rome at the age of 30, showing early a talent for administration that would serve him well throughout his life.

After his father’s death, around 574 Gregory transformed his family villa into an urban-based monastery called Saint Andrew’s, balancing his desire for contemplation with his public duty to serve others. In 579 Pope Pelagius II ordained Gregory a deacon and sent him to Constantinople as ambassador to the imperial court. Pelagius tasked Gregory to get help from the emperor so that Rome could fend off the attacking Lombards, but Gregory was not successful. After returning to Rome, Gregory was elected pope by acclamation in 590 after Pelagius II died of yet another plague.

As pope, Gregory faced a number of challenges, including continuing to defend Rome against outside aggression. In the absence of secular leadership that encouraged peace, a major feat of Gregory’s papacy was the way he calmed the political instability and stabilized the city’s economy.

Once he established stability, Gregory focused on the work of the church. Prolonged plague, famine, and war had brought waves of refugees to the city and plunged many into poverty. In the absence of other leadership, Gregory set the church to work.

Since the time of the apostles, Christians had received donations to distribute to the poor (see Romans 15:25–31, for example). However when Gregory became pope, church and state programs for poverty relief were not up to the size of the task. Gregory instituted a system of keeping track of donations, encouraged church leaders to seek out needy people, and stepped up production of food on church land. His ability to help the poor built his reputation among the city’s population, cementing his legacy.

His work focused not only on Rome; he also reorganized church mission work among non-Christian tribes to the north and west. In a program now known as the Gregorian Mission, he sent Augustine of Canterbury (d. 604), then prior of Saint Andrew’s, to evangelize the Anglo-Saxons of England.

Gregory’s understanding of civic engagement was influenced by his experience as an administrator, but also by his monastic commitments. Even while serving as papal administrator and pope, Gregory’s life and work were organized by monastic rhythms. His interest in monastic life and poverty relief also appear in writings such as the Life of Benedict.

A new Benedict

As monasticism progressed new varieties of consecrated life developed (see pp. 46–47) that in some cases were entirely dedicated to service “in the world”—especially in schools, hospitals, and organizations devoted to helping the poor, such as orphanages and food kitchens.

Though Protestant reformers rejected monasticism formally, they continued to read many monastic authors. In the twentieth century, examples of Protestant monastic-inspired life that arose included Taizé in France and Finkenwalde in Germany (see pp. 42–44).

Scottish American philosopher Alisdair MacIntyre concluded his famous After Virtue (1981) with a call to construct local monastic-style communities:

. . . within which civility and the intellectual and moral life can be sustained through the new dark ages which are already upon us. And if the tradition of the virtues was able to survive the horrors of the last dark ages, we are not entirely without grounds for hope. This time however the barbarians are not waiting beyond the frontiers; they have already been governing us for quite some time. And it is our lack of consciousness of this that constitutes part of our predicament. We are waiting not for a Godot [a reference to Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot] but for another—doubtless very different—St. Benedict.

Christians have used MacIntyre’s words to support strikingly different models of civic engagement, from the “New Monasticism” movements of the early 2000s to Rod Dreher’s The Benedict Option (2017). They have argued that monasticism was key to maintaining church and society in the tempestuous early Middle Ages, a tried and tested method of faithful Christian civic engagement for what appears to them to be a comparable time.

The concept of the “Dark Ages” is problematic in itself, let alone in comparison to contemporary society or politics. Yet a better understanding of civic engagement within the monastic tradition is still revelatory. Rather than hiding from the world, the monastic tradition at its best has prayed for it, administered it, taught it, nursed it, written about it, evangelized it, provided for it, traded with it, and welcomed its guests. CH

By Jason Zuidema

[Christian History originally published this article in Christian History Issue #141 in 2021]

Jason Zuidema is editor of Understanding the Consecrated Life in Canada: Critical Essays on Contemporary Trends and executive director of the North American Maritime Ministry Association.Next articles

Inside the monastery gates

A chief way monasteries engaged with their communities was showing hospitality

From royal saints to holy fools

The Eastern Orthodox tradition has often intertwined civic engagement with civic power

James C. SkedrosServing your neighbor

Luther’s theology of the common order of Christian love gave life to civil society

Jordan J. BallorTwo kingdoms

A selection of Luther’s musings on the role of Christians in civil society

Martin Luther